Credit

Credit markets have remained robust, even as interest rates have soared to multi-decade highs. In this interview, Damien McCann, portfolio manager for Capital Group’s American Funds® Multi-Sector Income Fund explains why he expects this resilience to continue and discusses the opportunities he sees in multi-sector credit portfolios designed to generate income from a combination of corporate bonds, emerging markets bonds and securitized credit.

What is your view on the state of credit markets today? Where are you seeing the opportunities and the risks?

Overall, this is a constructive backdrop for credit. I think credit markets are broadly investable today, and now is not the time to have a big underweight to credit. From a fundamental perspective, I expect improved economic growth. Our economists expect global gross domestic product (GDP) growth of about 3% in 2024. This is lower than the growth rates we saw in the years before the pandemic. But it is still solid, and the decline is attributable primarily to slower growth in China.

I also expect inflation to continue coming down gradually. Disinflation has been a bit slower than central banks would like, but there should still be enough space to begin lowering policy rates as we look out over the next few quarters. Additionally, corporate, consumer and emerging markets government balance sheets are not excessively leveraged and fairly stable overall.

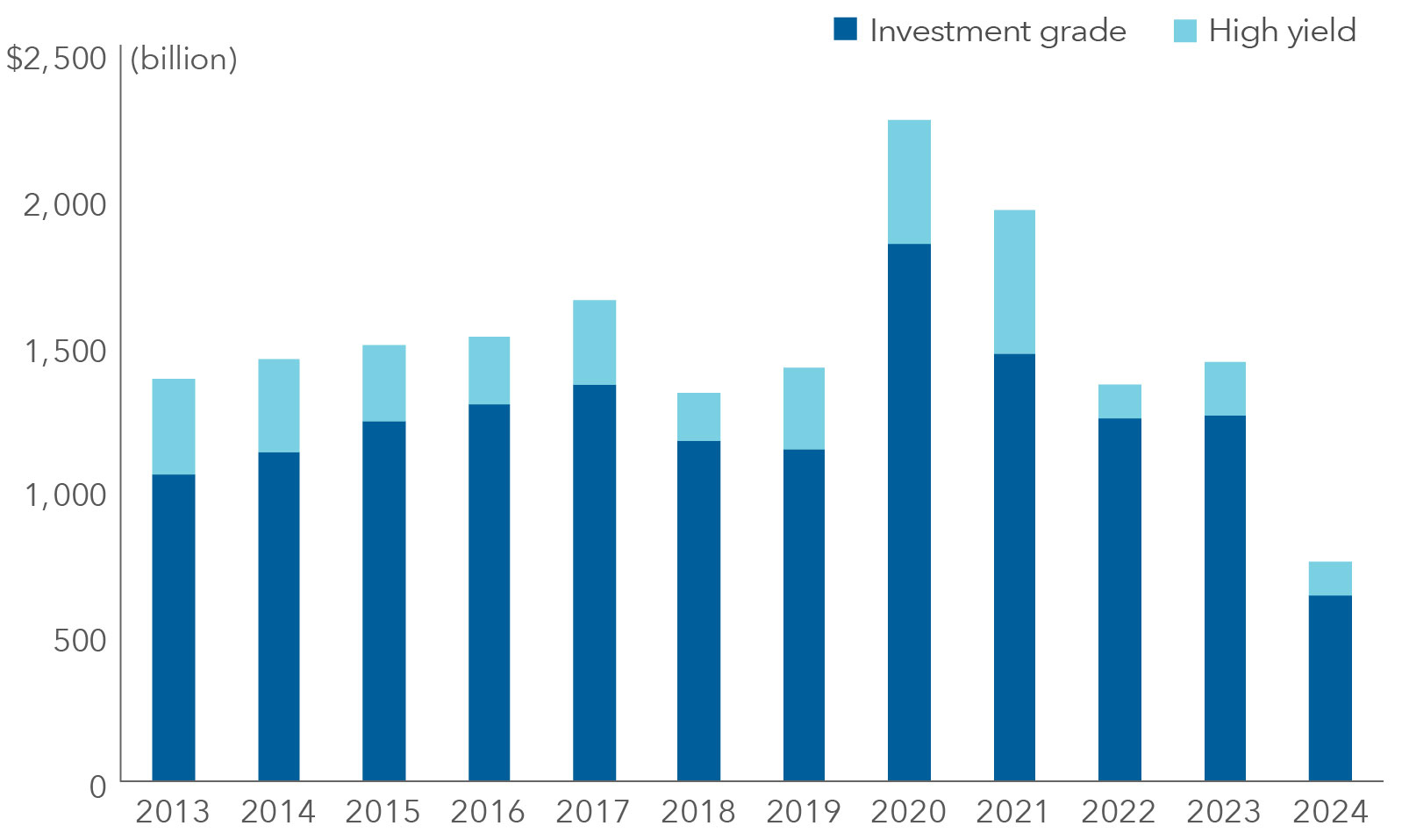

This isn't to say that credit fundamentals are fine everywhere, but the problems I see are more idiosyncratic and could be ascribed to individual industries or issuers. Technicals also appear supportive. Now that rates are a lot higher, borrowers are choosing to borrow less or for shorter periods of time. Higher rates are also creating more interest in credit from lenders and bond investors, such as ourselves.

This is reflected in significant inflows into bond funds. Cash is coming off the sidelines as investors are pulling out of money market funds and taking the opportunity to invest in elevated yields for a longer period of time.

Corporate bond issuance lags after pandemic surge

Source: SIFMA. Data as of April 30, 2024. Investment grade = BBB/Baa and above.

What about valuations? Spreads have tightened significantly this year. How is that factoring into your investment strategy?

Currently, I see the most attractive opportunities in investment-grade corporates and securitized credit. I see some risk in high yield, although it’s not really a concern about fundamentals but more of a concern that valuations have become excessive relative to other sectors.

It is true that spreads have tightened, but they remain in a normal range for a non-crisis period. My view is that, based on supportive fundamentals and technicals, it would be odd if spreads were much wider than they are today.

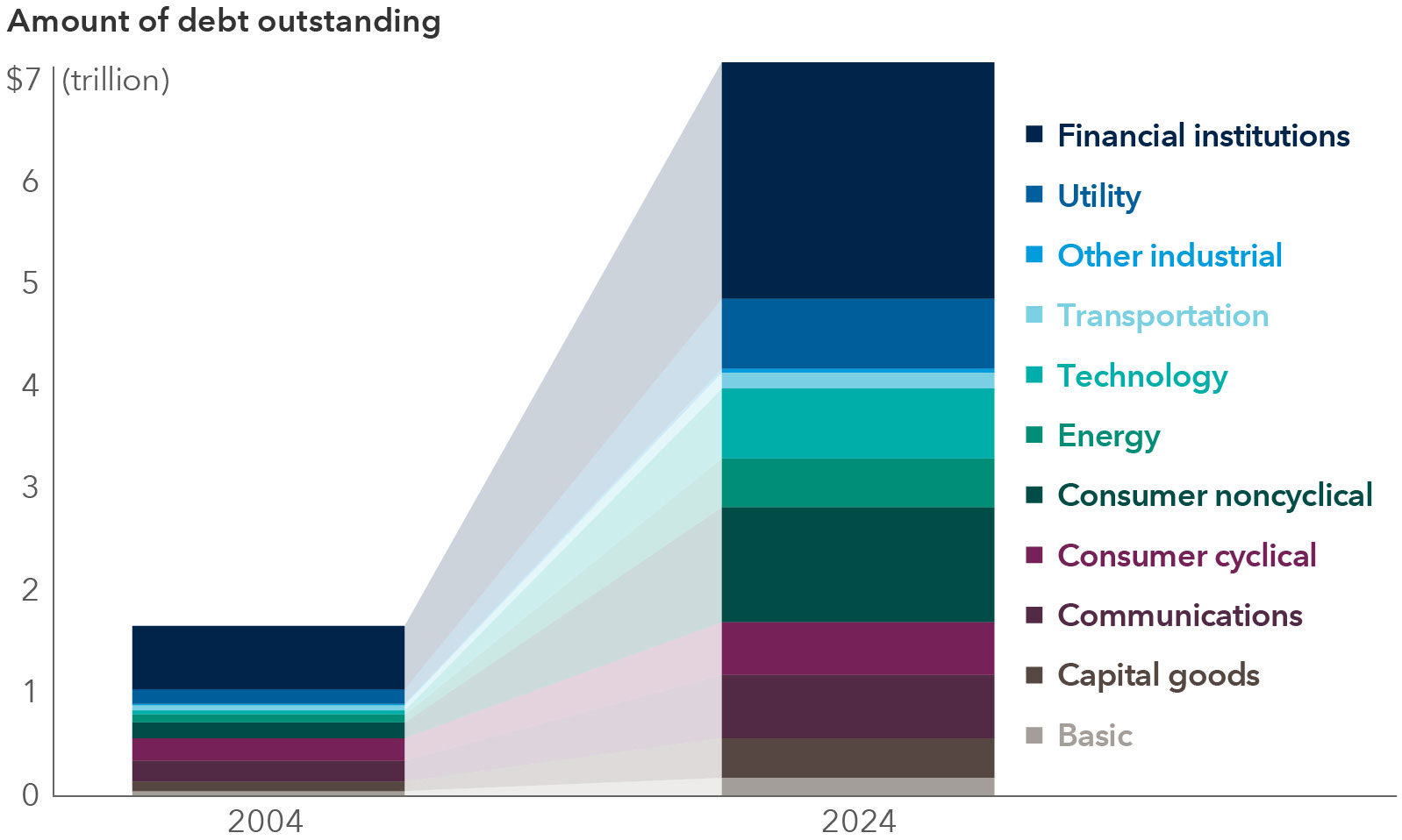

Also, credit markets are enormous, and spreads are not uniformly tight across sectors. Different sectors have distinct underlying credit drivers. A corporate borrower’s credit quality is determined by different factors than a sovereign issuer’s ability to repay, or a subprime auto borrower’s ability to service debt. As a result, valuations, yields and spreads are not the same across these markets, and they don’t move around in a perfectly correlated fashion.

Financials are among the largest issuers of corporate bonds. What is the state of the banking industry today?

We’ve seen quite a recovery from the events of March 2023. The root causes of Silicon Valley Bank’s collapse (among others) were linked to a combination of factors, including some unique customer concentrations and herd behavior, as well as excessive commercial real estate exposure and interest rate sensitivity in Treasury holdings.

We’re still waiting on all of the details, but we expect the Fed to further tighten regulations on banks as they did in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. This is likely going to mean banks need to hold more capital than they did before last March and maintain more liquid balance sheets.

In the U.S., the larger banks were already very well capitalized and remain so. They were able to provide support in concert with the Fed to stabilize markets and provide resolutions for the handful of banks that got into trouble.

All else being equal, I expect the incoming regulation will mean credit quality for banks is going to go up, and their return on equity is going to go down. That should be a relative positive for bond investors and a relative negative for equity investors.

As the Federal Reserve and other central banks lower rates, it should be broadly positive for financials. It should mean that net interest margins, a key measure of bank profitability, should improve as funding costs fall. Demand for loans could also improve across commercial, industrial and consumer sectors, including mortgages, when it becomes cheaper to borrow.

Investment-grade credit market has evolved and expanded

Source: Bloomberg. Chart shows sector allocations within the Bloomberg U.S. Corporate Investment Grade Index. Data as of May 29, 2024.

As a portfolio manager of multi-sector income strategies, where are you seeing opportunities, and where are you being more cautious in both investment grade and high-yield sectors?

If you look at 10-year BBB-rated corporates, which is arguably the core of the investment-grade market, spreads are not at historic tights and could tighten further.

More broadly in investment grade, we see opportunities in select pharmaceutical companies. These companies tend to be very good businesses with strong cash flows and demand that is not sensitive to the economy. There are some situations where pharmaceutical companies have made debt-financed acquisitions and are now going to use their free cash flow to repay that debt. As debt levels fall, we expect credit spreads to tighten. This would drive higher bond returns, which could be comparable to many of the return opportunities available in the high-yield market, but with a significantly lower risk profile.

We’re also finding value in certain utilities that are facing elevated wildfire risk but have credible plans to harden their distribution systems, thereby potentially reducing wildfire risk going forward.

At the sector level, I’m cautious on high yield. This is not because of the underlying credit fundamentals, but due to the ultra-tight spreads for many high-yield issuers, relative to history and compared to spreads in other sectors. Within high yield, at the industry level, I’m being very selective and careful in telecoms, cable and satellite companies. There are a number of companies here that are simply too levered for the more competitive environment that has emerged in those industries.

Where do you see opportunities in securitized credit?

Securitized credit plays an important role in multi-sector income portfolios as a diversifier to corporate and sovereign credit. The drivers of securitized credit are unique in areas like consumer lending, either secured or unsecured, sometimes tied to particular assets like car loans — or commercial real estate mortgages or non-agency residential mortgages or collateralized loan obligations.

I’d highlight subprime autos in this area. From a fundamental perspective, a strong job market supports borrowers’ ability to service their debt. We like the structure of these securities: They have shorter maturities, and the leverage declines over the life of the bond as borrowers make payments. In this context, 6% to 8% yields are quite attractive.

That being said, securitized credit overall is less liquid, and an important driver of excess returns over time in a multi-sector credit portfolio is shifting between sector exposures. It is harder to flex securitized exposure up and down, given the lower liquidity. Therefore, it can make sense to limit its size in portfolios and focus more on sectors where it is possible to be more flexible.

What’s your process for deciding relative value among sectors?

Our approach to sector allocation within multi-sector portfolios relies on a combination of top-down and bottom-up inputs, as well as viewing sector allocations through a risk lens.

The starting point for our sector allocation strategy is the Portfolio Strategy Group’s views on the overall attractiveness of credit. This sets the overall tone for the amount of credit risk we’ll take in multi-sector portfolios.

Next, we look at relative valuations between sectors in a historical context, going back multiple decades. Relative valuations have been cyclical and have tended to revert to the mean over time, and we believe that behavior should continue. These patterns have been driven by a combination of economic and market cycles, as well as underlying borrower behavior.

Take the history of the high-yield sector as an example: During periods of strong markets and low volatility, high-yield issuers tend to gradually take more risk in how they manage their businesses and balance sheets. Eventually, this risk- taking behavior goes too far, which is often revealed when there’s a slowdown in the economy. Then high-yield borrowers must course correct, and you'll see cost cutting, reduced capital spending, and often asset sales, as they look to repay debt and shore up operations and profitability. This pattern has played out again and again over time.

With this in mind, we often take a countercyclical approach to sector allocation, reducing exposure to higher yielding, lower quality sectors after periods of spread tightening and strong results, while simultaneously expanding exposure to lower yielding, higher quality sectors. We then look to add back exposure to higher yielding, lower quality sectors after a period of spread widening and lower returns, in anticipation of issuers in that sector taking steps to improve credit quality.

A quantitative model also helps us identify relative valuation dislocations at the sector level. We take the quant model’s signals as a starting point for sector allocation, and then overlay forward-looking views on fundamentals and technicals from each of the sector level portfolio management and analyst teams across high yield, investment grade, emerging markets, and securitized credit.

Lastly, we look at the potential risk factors that could affect different sector allocations, considering various economic and market scenarios so that we understand correlations and the potential volatility of an overall multi-sector income portfolio.

Bloomberg U.S. Corporate Investment Grade Index represents the universe of investment grade, publicly issued U.S. corporate and specified foreign debentures and secured notes that meet the specified maturity, liquidity, and quality requirements. This index is unmanaged, and its results include reinvested distributions but do not reflect the effect of sales charges, commissions, account fees, expenses or U.S. federal income taxes.

The use of derivatives involves a variety of risks, which may be different from, or greater than, the risks associated with investing in traditional securities, such as stocks and bonds.

Don't miss our latest insights.

Our latest insights

-

-

Emerging Markets

-

Global Equities

-

Economic Indicators

-

RELATED INSIGHTS

-

-

Emerging Markets

-

Economic Indicators

Don’t miss out

Get the Capital Ideas newsletter in your inbox every other week

Damien McCann

Damien McCann