U.S. Equities

Portfolio Construction

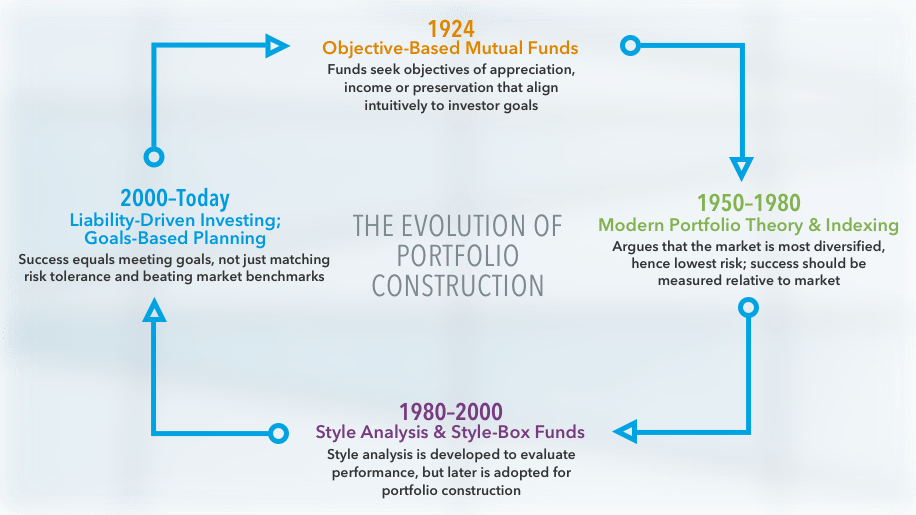

- The earliest mutual funds pursued clear objectives aligned with investor goals.

- Research in the 1950s and 60s argued that broad market indexes were the most diversified portfolios.

- Style analysis was developed in the 1970s and 80s to evaluate fund results, but applied to build portfolios.

- The adoption of liability-driven and goals-based wealth management is challenging the idea of index-relative performance measurement and style-box investing.

- As advisors seek to deliver against concrete and personal client goals, they may once again find value in flexible mandates with objectives that align clearly with client needs.

They say fashion goes through cycles. The same might be true in portfolio construction, with the rise of goals-based wealth management. Financial professionals increasingly recognize that real-world goals should guide portfolio construction, alongside traditional inputs like market indexes. But the tools of portfolio construction have not caught up yet, and we need new thinking in order to meet the needs of 21st century investors.

Fortunately, the past provides a partial answer to this dilemma. To explain where portfolio construction might be going, we have to understand how we got here. So first, we will give a brief history lesson before outlining where we think portfolio construction is headed.

Where it all began

The earliest mutual funds pursued clear objectives of appreciation, income or stability that aligned intuitively with investor goals, and research found that fund attributes typically matched those objectives; appreciation-oriented funds tended to have higher returns, and income-oriented funds tended to have lower risk. (McDonald, 1974).

But three developments caused the world of investing to move away from the clarity of this objective-based approach. First came “Modern Portfolio Theory” in 1952, which laid out a new way to measure portfolio risk based on volatility.* According to Harry Markowitz, who developed the theory’s foundations and won a Nobel Prize for his work, investors should evaluate correlations between each of their investments and seek to build diversified portfolios that have the highest expected return for their risk tolerance, along a mathematically calculated “efficient frontier.”

Next came the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM), often credited to Bill Sharpe in 1964 (Sharpe, 1964). CAPM argued that the “market” portfolio of all listed companies is most diversified, and in a world where all investors seek to maximize risk-adjusted returns, a company’s equity market capitalization represents aggregate consensus for its optimal portfolio weight. Thus, all investors could simply hold proportions of the market-cap-weighted index consistent with their risk tolerance.

This put indexes at the core of investment thinking, and suggested that active management (defined as any deviation from the index) is risky and appropriate only if it consistently beats the index. In the early 1970s, this thinking leapt from academic journals into the marketplace and gave birth to passive investing when Wells Fargo and Vanguard launched index-tracking funds for institutional and retail clients, respectively.

Style comes in style

Finally, the idea of “style” arrived. It started when researchers noticed that a portfolio of “value” (i.e., low price-to-earnings ratio) and “small-cap” stocks had better risk-adjusted returns than the market as a whole (Basu, 1977; Banz, 1981). “Style” in its infancy was not used in the same way it is today, however. In fact, style was seen as a way to evaluate portfolios, not build them. Pension consultants — Russell in 1986 and Wilshire in 1987 — launched indexes that divided the overall market into value/growth and large/small sub-components. These indexes helped categorize funds into sensible peer groups, and also to calculate performance benchmarks (Sharpe, 1988).

Style was initially descriptive and grouped similar funds across factors that were important to results. However, a descriptive tool quickly became prescriptive, as consultants started to advocate that a diversified portfolio must hold each of the different styles. The argument of style diversification was a departure from the early research that emphasized specific styles (i.e., value over growth/small cap over large cap), yet had some intuitive appeal, and became quite popular.

Morningstar’s launch of its style-box framework (a nine-square grid that shows the investment style of a particular fund) further popularized style-based strategies. As a result, investment mandates shifted away from investor-centric objectives like appreciation or income; instead, managers sought to deliver a style or market exposure while beating a peer group of funds (Bernstein, 1995).

Everything old is new again

Two developments in the 21st century have drawn style-based investing into question.

First, a growing body of research demonstrated that constraints on investment universe and strategy were costly and hurt performance (Clarke, et al., 2000). Russ Wermers extended this general argument to style boxes in his 2002 paper, finding a link between style drift and improved fund results (Wermers, 2002). Indeed, Morningstar itself has called style boxes “descriptive, not prescriptive.”

Second, pension funds began adopting liability-driven investing (LDI). In the aftermath of the dot-com crash, pension funds found that a combination of declining interest rates and falling equity prices caused their funded ratios (i.e., the value of their assets to liabilities) to fall — even when many of their fund managers beat market benchmarks. Pension managers realized that success meant meeting pension promises, not beating market indexes. They began to invest in custom mandates that focused on matching their unique future liabilities, not beating broad fixed-income indexes.

Goals come to the fore

Today goals-based wealth management has begun to take hold amongst the investment community. Like LDI, the goals-based approach has sought to emphasize unique client goals in favor of a singular focus on risk tolerance and market benchmarks (Chhabra, 2005).

Industry leaders are following suit. Harvard’s endowment recently acknowledged that it had overemphasized individual asset-class benchmarks and is shifting its approach to focus on outcomes. “While this silo approach does bring the benefits of specialization, it has also created some unintended consequences … This model has also created an overemphasis on individual asset class benchmarks that I believe does not lead to the best investment thinking for a major endowment, “ wrote N.P. Narveka, CEO of Harvard Management Company.

Where we are headed

The move toward goals-based wealth management will require a rethink of portfolio construction and manager selection. In our view, objective-based investing will return – but it will build on previous academic research and complement existing approaches. Here is how:

- As with pension CFOs before them, investment advisors will need to evaluate how their portfolios align with client goals – not just benchmark indexes – and which fund attributes matter most.

- As a result, there will be rising demand for objective-based mandates that link more directly to investor goals, rather than simply providing asset class or style exposure.

- A focus on outcomes may lead to another change: relaxing style or geographic constraints in portfolios by adding flexible mandates that can invest across asset classes, styles and geographies to pursue specific investment objectives.

- Those who retain some of the ideas around diversification embedded in style boxes — but who also use more flexible, objective-based mandates — may well have the most success.

Of course, no one really knows exactly where we are heading. What we do know is that objective-based investing appears to be gaining momentum, and it is unlikely that we will continue to build portfolios the same way in the decades to come. This is an exciting area of evolution and one that we will seek to address in future research.

*More technically, volatility according to Markowitz is represented as the variance of returns — or equivalently, the square of the standard deviation of returns (Markowitz, 1952).

Works cited

Banz, Rolf W., “The relationship between return and market value of common stocks,” Journal of Financial Economics 9.1, 1981, pages 3–18.

Basu, Sanjoy, “Investment performance of common stocks in relation to their price‐earnings ratios: A test of the efficient market hypothesis,” The Journal of Finance 32.3, 1977, pages 663–682.

Bernstein, Richard, “Style investing: Unique insight into equity management,” Vol. 31, John Wiley & Sons, 1995.

Chhabra, Ashvin, “Beyond Markowitz: A Comprehensive Wealth Allocation Framework for Individual Investors,” The Journal of Wealth Management, Spring 2005, pages 8–34.

Clarke, Roger, Harindra de Silva, and Steven Thorley, “Portfolio Constraints and the Fundamental Law of Active Management,” Financial Analysts Journal, Vol. 58, No. 5, September/ October 2000, pages 48–66.

Markowitz, Harry, “Portfolio selection,” The Journal of Finance 7.1, 1952, pages 77–91.

McDonald, J.G., “Objectives and Performance of Mutual Funds, 1960-1969,” Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, June 1974, pages 311–333.

Sharpe, William F., “Capital asset prices: A theory of market equilibrium under conditions of risk,” The Journal of Finance 19.3, 1964, pages 425–442.

Sharpe, William F., “Determining a fund’s effective asset mix,” Investment Management Review 2.6, 1988, pages 59–69.

Wermers, Russ, “A matter of style,” Canadian Investment Review, Summer 2002, page 42.

Our latest insights

-

-

Global Equities

-

Economic Indicators

-

-

Related Insights

-

Portfolio Construction

-

Portfolio Construction

-

Portfolio Construction

Don’t miss out

Get the Capital Ideas newsletter in your inbox every other week

Statements attributed to an individual represent the opinions of that individual as of the date published and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of Capital Group or its affiliates. This information is intended to highlight issues and should not be considered advice, an endorsement or a recommendation.

Brett Hammond

Brett Hammond

Sunder Ramkumar

Sunder Ramkumar