International

International equities have lagged U.S. markets over the past decade. And with major central banks moving in a similar direction and economies increasingly interconnected, they no longer provide a high level of portfolio diversification. So why bother?

I would ask a simple question: If you go fishing, you don’t say that I’ll fish in only half the lake. It’s no different in the investing world. Why would you willingly ignore more than half of the investing universe? As someone who has invested in most markets of the world for three decades, I’ll make a few simple observations:

- Some of the world’s best-run and fastest-growing companies are based outside the U.S.

- A large swath of companies paying handsome dividends can be found in Europe and Asia.

- The corporate culture of share buybacks, which at times results in excessive leverage on the balance sheet, is less prevalent outside the U.S., which in my view makes for more attractive long-term investments.

In order to have a well-rounded and robust portfolio of stocks, investing in international markets is a must — even if you think the U.S. market in aggregate will continue to do better in the short term. As I look out over the next few years, I see a few key themes related to investing abroad:

Looking for growth? Invest alongside the Chinese consumer.

China’s vast middle class and increasingly wealthy upper middle class will continue to be among the top drivers of global growth.

In the past decade, China was busy building out the infrastructure of its economy and, as a result, drove global demand for commodities and all things industrial. It still maintains enormous influence on the industrial economy. But what’s more interesting are the evolving tastes of the Chinese consumer. Consumption in China has grown by at least 5% a year pretty consistently over the last 10 years. It is capital expenditure and exports that have been more volatile, hence the concerns around total GDP growth.

As the population gets wealthier, their priorities are changing. For example, infant nutrition, health and hygiene have become top priorities. That’s great for a company like Reckitt Benckiser, a Dutch British multinational that specializes in baby formula Enfamil and other personal care products. French food products powerhouse Danone is capitalizing on escalating demand for yogurt and other dairy foods in China. L’Oreal is another good example. The company has overcome a slowdown in Europe’s economies by tapping into the strong demand for cosmetics in China, India and other Asian markets. It has, in fact, managed to grow revenues by around 15% year over year. If you just think of L’Oreal as a France-based company, you are missing the point and the opportunity.

We can’t ignore Chinese consumers’ fascination with luxury brands like Gucci and Louis Vuitton. And in my opinion, the Europeans are the best at creating luxury brands. Kering is the French luxury goods company that owns Gucci as well as other celebrated names like Yves Saint Laurent, Alexander McQueen and Balenciaga. Focusing on the Asian consumer broadly and the Chinese consumer specifically, Kering grew top-line revenue by more than 25% in 2018 over the prior year.

In addition to following consumer demand patterns, we closely follow how corporate management is navigating these trends. Take LVMH Group, the holding company that owns, among many others, the iconic Louis Vuitton brand. The company has exhibited a highly disciplined management of its cash flow. It has redeployed much of its cash flow to expand its portfolio of brands while simultaneously pursuing a policy of growing the dividend initiated by the controlling Arnault family a dozen years ago.

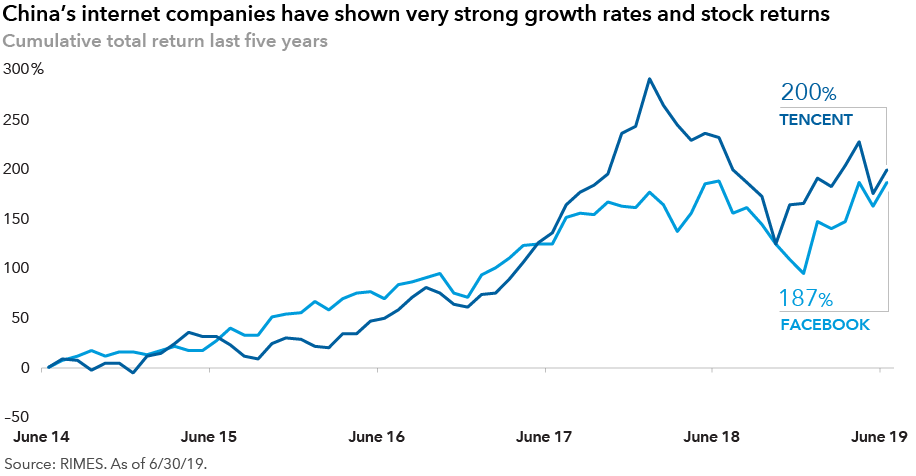

Within China, I find that internet companies are nimble and responsive to changing consumer behavior. Take internet giant Tencent as an example. At the start of this decade, it took off as a very successful gaming company. It quickly identified retail as a rapidly evolving area, so it started an online retail platform. Then it recognized that electronic payments would be the next wave of evolution and started a payment platform. It is now entering a phase where it is looking at software — particularly industrial software — and management of the cloud. The company is constantly moving into the next phase of opportunity. In the context of China, it has been a phenomenal growth opportunity.

Looking for dividend income? Many technology and health care firms offer a dividend yield above 3%.

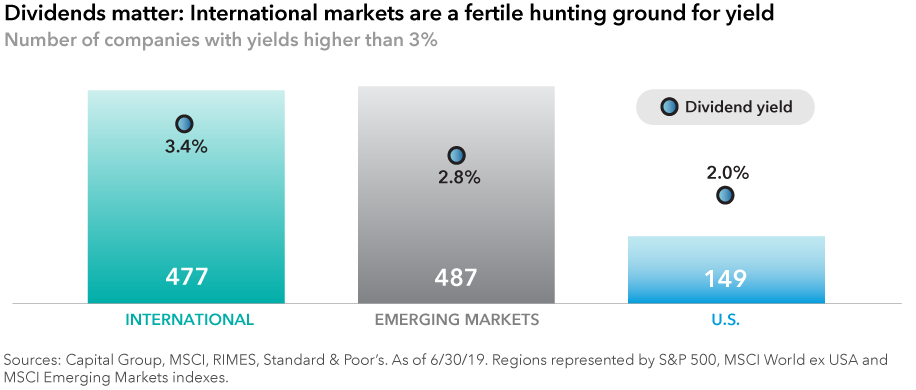

Many high-flying technology companies like Netflix and Facebook are in the U.S. But the so-called nuts and bolts of the internet are made in Europe and Asia. Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing (better known as TSMC) and Samsung make the majority of the world’s semiconductors. Dutch company ASML is the world’s largest supplier of lithography systems used to build semiconductors and machines used in the production of integrated circuits. Investing in stocks of these companies offers exposure to fast-growing areas of technology with a record of paying dividends, which has historically helped lower volatility and provide better downside protection in declining markets. TSMC and Samsung both have a dividend yield above 3% (as of June 30th).

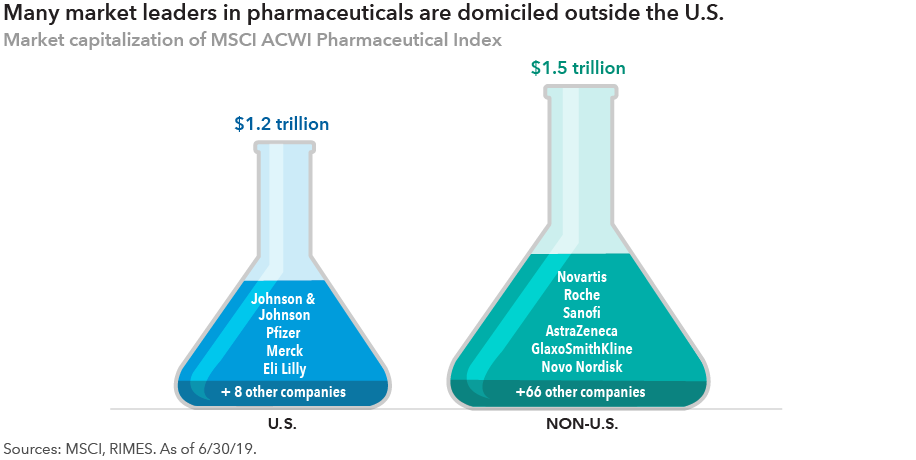

Health care is another area of continuing interest for us. Europe is home to many high-quality pharmaceutical companies that are leading in immunotherapy, an area with applications ranging from treatment of various types of cancer to obesity. Roche and Novartis are the largest and most obvious; they offer the potential for capital appreciation with an attractive dividend yield above 3% (as of June 30th). But our analysts believe there are many other smaller companies with viable drugs in their pipelines.

Fundamentals matter: Europe and Asia are home to some very well-run companies.

After I have decided that I like the fundamentals of a company, I always go back to basics, which for me is that a stock’s return is capital appreciation plus the dividend. The reality today is that dividend yields are higher outside the U.S., and capital appreciation may be higher than it seems on the surface. Many companies also have a strong culture of paying dividends — they are very focused on paying the cash flow back to shareholders. When I look at operating profit rather than EPS, the growth rates of many European companies are comparable to those in the U.S.

In the U.S. there is tremendous focus on buybacks to sustain a steady growth of earnings per share (EPS). There is less focus on operating profit and organic growth. Companies are taking on debt to buy back stock. As a result, the EPS grows much faster than the operating profit. That is not a common tradition outside the U.S. Certain companies do it, but on a far smaller scale and with less frequency. And even when they do, they don't often cancel the stock, so it does not translate to EPS growth.

Companies cannot borrow indefinitely to pay dividends. Nor can they take too much of the operating cash flow to pay dividends to shareholders because that usually comes at the cost of the reinvestment cycle.

A well-balanced company is one that is able to take some of its operating cash flow, deploy it to the needs of the business and then look at other sources of growth — be it through acquisition or otherwise. At the end of the day, there should still be some cash left to service a stable but growing dividend policy. There is a discipline both to the management of the business and the capital structure. In my experience, those companies that are able to balance both tend to have very good stock price evolution over extended periods of time. And those are the companies that I look to invest in for the long term.

Investing outside the United States involves risks, such as currency fluctuations, periods of illiquidity and price volatility. These risks may be heightened in connection with investments in developing countries.

Our latest insights

-

-

Market Volatility

-

Market Volatility

-

World Markets Review

-

Don’t miss out

Get the Capital Ideas newsletter in your inbox every other week

Statements attributed to an individual represent the opinions of that individual as of the date published and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of Capital Group or its affiliates. This information is intended to highlight issues and should not be considered advice, an endorsement or a recommendation.

Gerald Du Manoir

Gerald Du Manoir