Bonds

The 10-year Treasury yield topped 3% last week after rising steadily since the beginning of the year. How much can bond yields rise and what are the implications for stocks? Three of our portfolio managers provide their views.

Gradual rate hikes to continue as inflation poised to pick up.

Ritchie Tuazon

Portfolio manager, Strategic Bond Fund, Inflation Linked Bond Fund

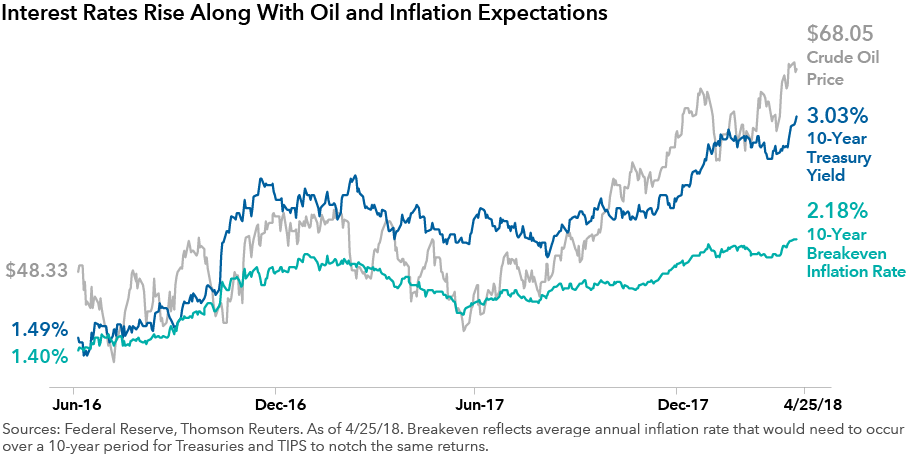

Bond yields have moved higher as inflation has risen. Commodities broadly, and especially gasoline prices, have risen meaningfully in recent months.

More importantly, wages have risen and will feed into inflation. There is a debate in the market as to whether the traditional relationship between wages and inflation, also known as the Phillips curve, is not as strong as it used to be. I think sooner or later, tighter wages will feed into inflation.

Inflation, as measured by the consumer price index, could touch 3% in the middle of this year and then drift lower at the end of the year. Core inflation, which is the measure that strips out volatile energy and food prices, could be up 2.6% by the end of 2018.

It is worth remembering that we are in the later phases of this economic cycle. And the Federal Reserve is not only raising interest rates, it is also removing money from the system through quantitative tightening. Given a tightening of financial conditions, there's certainly a reasonable chance that financial markets could wobble.

So the Fed will watch and calibrate its rate cycle based the impact of its actions and other factors on markets and the broader economy. There could be up to three further hikes this year, though two hikes would also be reasonable. If there is one word that summarizes the Fed’s approach, it’s “gradual.”

In this environment, I don’t expect 10-year Treasury yields to move a lot higher in any sustained way. A range of approximately 2.75% to 3.25% for the remainder of 2018 appears reasonable. And within that, higher than 3% may be more likely than lower than 3%, in part due to increased Treasury supply to fund the larger deficits.

Rising interest rates can be good for stocks.

Jim Lovelace

Portfolio manager, Capital Income Builder

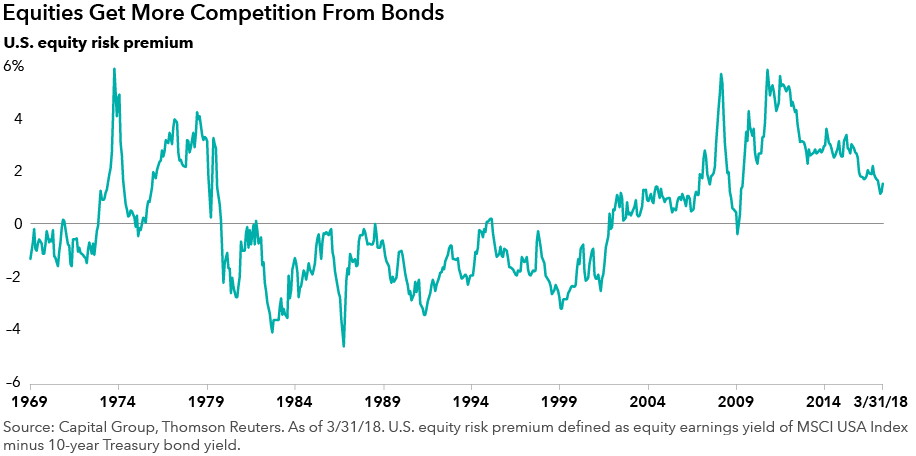

Although the conventional wisdom is that interest rate increases are bad for stocks, the relationship really depends on the reason that rates are moving higher. If rates are going up because the economy is healthy, then we can be in a period when both interest rates and stocks can go up.

For me, reaching 3% is a significant moment in that it means the economy has fully recovered from the financial crisis and is healthy. We have gone from an extremely low level of interest rates to what will be a more normal level of 3% to 4% yields. And that’s probably good for equity valuations.

The real debate is: when does that change? When do rising interest rates reflect an overheated economy? I don’t think we are there yet, as inflation remains modest and rates are rising from a pretty low level.

Similarly, it’s not always the case that rising rates are bad for dividend-paying stocks. The dividend-paying universe of stocks has evolved and electric utilities are among the few areas that still have a tight relationship to bond yields. The telecommunications companies don’t trade in line with rates as much as utilities do, and consumer products companies hardly trade with interest rates at all. On the other hand, financials, and especially banks, benefit from rising rates.

We may continue to see sharp market moves for a period of time as the benchmark 10-year yield touches key levels — 3% or 3.25%. But these can be driven by program trades or large positions from select market participants getting flushed out. The trends that impact markets long-term — the gravitational pulls — are generally more subtle and not captured in one-day moves, but occur over a number of months.

I am less concerned about the impact of rising rates on markets than the possibility of trade wars and the impact it may have on the economy and market sentiment. As a portfolio manager in a multi-asset fund, Capital Income Builder, we reduced the equity exposure in favor of fixed income over the last year, albeit from historically high levels of equity in the fund.

The equity risk premium has declined as rates have risen. It is stocks' earnings yield minus the Treasury yield.

Emerging markets bonds could hold their own.

Rob Neithart

Portfolio manager, Emerging Markets Bond Fund, World Bond Fund

From a global perspective, as bond yields continue to rise in the U.S., it becomes increasingly attractive versus other developed markets. Higher relative rates should also be supportive for the dollar in the near-term. From the perspective of valuations, however, a stable to weaker dollar seems more likely over time.

For emerging markets, rising U.S. interest rates have historically had a negative impact. But emerging markets economies have undergone profound changes in the past two decades.

Economic and monetary cycles are much less tied to the U.S. It’s no longer the case that they have to raise interest rates when the U.S. does. Also, many markets have well-developed local bond markets with a local investor base, even though that base may not be as deep as in some developed markets.

Many economies in the emerging markets are at the early or middle stages of their economic growth cycle, and that has a momentum of its own. Overall, they’re well positioned to handle modestly higher U.S. yields. There’s still decent return potential in emerging markets debt, even after the strong rally of the past year or so.

Investing outside the United States involves risks, such as currency fluctuations, periods of illiquidity and price volatility, as more fully described in the prospectus. These risks may be heightened in connection with investments in developing countries.

MSCI does not approve, review or produce reports published on this site, makes no express or implied warranties or representations and is not liable whatsoever for any data represented. You may not redistribute MSCI data or use it as a basis for other indices or investment products.

Our latest insights

-

-

Emerging Markets

-

Global Equities

-

Economic Indicators

-

Don’t miss out

Get the Capital Ideas newsletter in your inbox every other week

Statements attributed to an individual represent the opinions of that individual as of the date published and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of Capital Group or its affiliates. This information is intended to highlight issues and should not be considered advice, an endorsement or a recommendation.

Jim Lovelace

Jim Lovelace

Rob Neithart

Rob Neithart

Ritchie Tuazon

Ritchie Tuazon