Municipal Bonds

Global Equities

This past winter I celebrated my 35th anniversary in the fund management business, and that milestone prompted me to start jotting down lessons I’ve learned along the way. I thought it might also be useful to share some perspective on how I’ve come to accept market crises as both inevitable and frequent, and how I’ve learned to manage through them.

I stumbled into this industry in 1987 because the China‐focused consulting boutique I worked for was going bust and my wife was pregnant with our first child. I talked to a headhunter who asked if I had considered equity research. Given my somewhat unconventional background, she said the only fund management firm in New York that might consider hiring me was Sanford Bernstein. It didn’t hurt that like Bernstein’s then-president, Lew Sanders, I had once driven a taxicab. Amazingly enough, it worked.

Market disturbances are a fact of life

Sources: MSCI, RIMES. As of August 31, 2023. Data is indexed to 100 on January 1, 1987, based on the MSCI World Index from January 1, 1987, through December 31, 1987, the MSCI ACWI with gross returns from January 1, 1988, through December 31, 2000, and the MSCI ACWI with net returns thereafter. Shown on a logarithmic scale. Past results are not predictive of results in future periods.

A frequent acquaintance with market crises

Knowing almost nothing about company analysis or portfolio management, I became a generalist equity analyst some three weeks before the October 1987 market crash.

So a career begun in crisis has been marked by it ever since. Over my 35 years as an investor, I have lived through 23 market shocks, including the 1987 crash, the bursting of the technology bubble, the global financial crisis, COVID-19, the Ukraine war and most recently the rise of global inflation.

I mention these events only to highlight the fact that market disruptions are inevitable. It’s just a matter of time before the next. My list suggests it happens every 16 months or so.

Hear more on this topic from Steve Watson:

An early introduction to dividends

When I began as an analyst, Bernstein’s investment process was driven by their proprietary dividend discount model. Early on I was imbued with the idea that dividends are important, and from a theoretical standpoint, companies are worth the current value of all the future dividends they'll pay.

My big takeaway was this: Over the long term, share prices are more volatile than earnings. This is because markets are driven by emotion perhaps as much as by the cool quantification of the value of firms. That has guided my investment philosophy ever since: I watch for the extremes of sentiment change and attempt to benefit from them.

But just selling the beloved firms and buying the mistrusted isn’t in and of itself a recipe for success. Couple the contrarian philosophy with an informed judgment about future profits, however, and there is power to the approach. That’s why I listen carefully to what our analysts at Capital think about where they see company returns headed.

A global citizen in search of a new home

Before I began as an investment analyst I worked on China business development as well as the restructuring of Venezuela’s public sector debt, having previously studied at both the undergrad and graduate levels in Europe and China. I considered myself a citizen of the world and wanted to globalize my investment work.

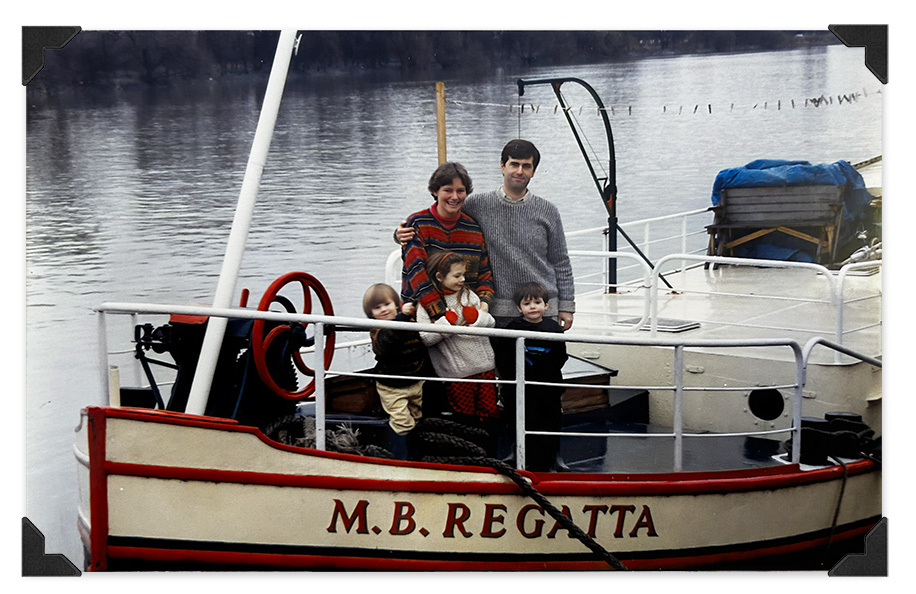

When I joined Capital Group in late 1989, I was thrilled to pack up my young family and head to London. Even 30 years ago, I found U.K. property prices ridiculously high, so we instead lived on a boat in the Thames River. A glorious adventure, but I won’t go into detail here.

Steve Watson and his young family aboard their London home in the early 1990s.

Early successes covering U.K. utilities

Initially I covered European utilities, starting with the recently privatized U.K. water firms. The privatization process had been a political minefield, and opposition was feverish. Selling the industry had been a must for the government, however, as the system was collapsing. Huge capital expenditure was required to get things in shape. Prices would need to rise, and cash flows would need to grow. The resulting dividend streams were going to be attractive, but all the political drama hindered valuations. Just my thing!

Fortunately for me, Capital Income Builder®, an equity income mutual fund, had been launched two years before I joined Capital, and the fund was open to investment ideas offering a combination of strong current yield and rising dividends. In addition, Jon Lovelace, son of Capital’s founder and the driving force behind the creation of the fund, regularly visited London. JL, as we called him, was receptive to my U.K. utility ideas. I was lucky enough to spend a fair amount of time with him, visiting companies and sharing ideas about investing.

Bumps along the road

The water and electricity utilities I recommended initially faced tough sledding. As the U.K. general election of 1992 approached, the Labour Party was making noises about renationalization. Utility shares went into freefall. I retreated into a state of fear about how it would end. Fortunately, JL happened to be visiting London at the time and we sat down for a discussion about possible outcomes. I suggested that renationalization would be too expensive for any future government, and that prices had to rise to facilitate the capital expenditure plans in place. JL concluded, “Well, I think we should be buying then.” And buy we did. And, as luck had it, Labour lost in a surprise upset, the sector soared, and I learned a lesson about not caving in to fear when things are against you.

In the years since, I have had the privilege to serve as a portfolio manager for Capital Income Builder as well as growth-and-income and growth strategies, including New Perspective Fund®.

An encounter with disaster

The biggest failure of my analyst career was Eurotunnel. In 1993, five years after its IPO, the company was a mess. The under‐the‐English‐Channel rail project was late and over budget. Management was in disarray while the largely French retail investor base was in revolt. Clearly there was fodder here for the contrarian.

Construction delays, cost overruns, new safety regulations, the French government’s refusal to halt subsidies to their Channel ferries and disappointing traffic derailed the project. From the recommendation price of GBP 4.00, the share rose to about GBP 5.60 and then began a sad slide toward zero. By late 1995 we had seen the writing on the wall and sold with a loss of around 80%.

A fresh perspective from Hong Kong

In 1999 I was asked to move to Hong Kong to help build Capital’s presence there; the Watsons arrived in early 2000. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) followed three years later. With many of the hallmarks now familiar to us from the COVID-19 pandemic, SARS hit Asian economies and markets hard. It was in that tough environment that I took on my new role as Greater China property analyst.

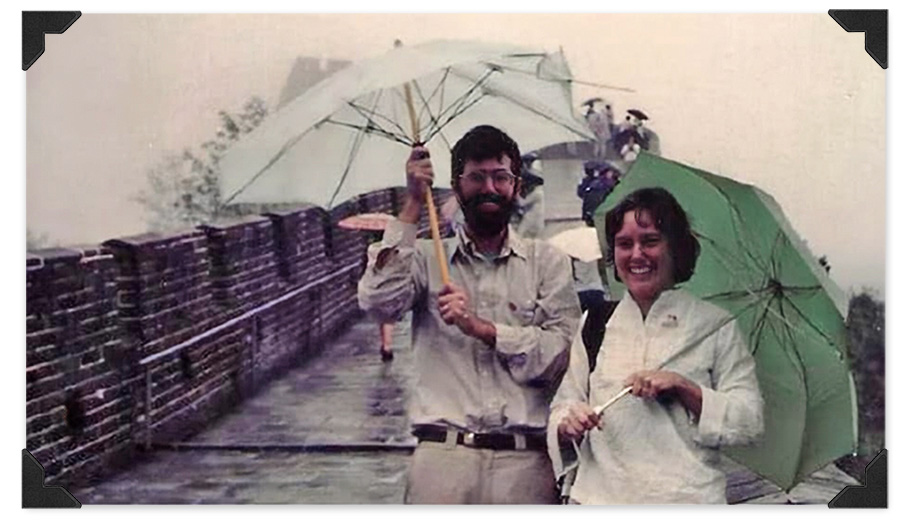

Steve Watson and his wife, Barbara, visiting the Great Wall of China in 1981.

Contrarian that I am, the collapse of Hong Kong property prices gave me useful opportunities once prices began to recover.

In the 23 years I’ve lived in Hong Kong and followed China closely, I’ve witnessed periods of tremendous growth along with challenges including regulatory clampdowns on entire industries and restrictive zero-COVID policies. Today, China is a tough market. It's not done well for several years. Interestingly though, it's done a bit better than emerging markets as a whole, but I believe it’s overlooked because people are so focused on the country’s disappointing returns.

There's a great debate raging globally, and we have an interesting debate within Capital along the same lines. Will China return to growth? I think it will. And I think that what may be the world's most disliked market can offer some pretty good returns. That's probably my most contrarian view today. I have a greater concentration of China and China-related investments in the portfolios I manage than most of my colleagues.

A final word on surviving crisis

Market shocks and crises are simply part of the investing landscape. They are painful, but eventually we recover. And it's easy to say at moments of crisis that I'm going to wait for clarity before I invest. I want to see the catalysts for a turnaround.

I've concluded that it's just not worth it to try and time things. We’re always looking for value. We're always weighing. We're always judging. But my own attempts to be clever about building cash and going more defensive haven't paid off very well.

What has worked for me as a portfolio manager is the collaboration with our analysts — who know the companies we can invest in better than I ever will — to get a sense of intrinsic value. And then I can do my own thing trying to decide where the market is wrong, over or underestimating fundamental values, and then invest accordingly, while doing my best to remain patient and focus on long-term results.

So that's what I do. And it enables me to look beyond crises because the crises seem like such a constant. So yes, this too shall pass. And I'll be relatively fully invested, most of the time.

Investing outside the United States involves risks, such as currency fluctuations, periods of illiquidity and price volatility, as more fully described in the prospectus. These risks may be heightened in connection with investments in developing countries. Small-company stocks entail additional risks, and they can fluctuate in price more than larger company stocks.

The market indexes are unmanaged and, therefore, have no expenses. Investors cannot invest directly in an index.

MSCI All Country World Index is a free float-adjusted, market capitalization-weighted index designed to measure equity market results in the global developed and emerging markets, consisting of more than 40 developed and emerging market country indexes.

MSCI has not approved, reviewed or produced this report, makes no express or implied warranties or representations and is not liable whatsoever for any data in the report. You may not redistribute the MSCI data or use it as a basis for other indices or investment products.

Our latest insights

-

-

-

Emerging Markets

-

Global Equities

-

Economic Indicators

RELATED INSIGHTS

-

Global Equities

-

-

Markets & Economy

Never miss an insight

The Capital Ideas newsletter delivers weekly insights straight to your inbox.

Steve Watson

Steve Watson