Market Volatility

Monetary Policy

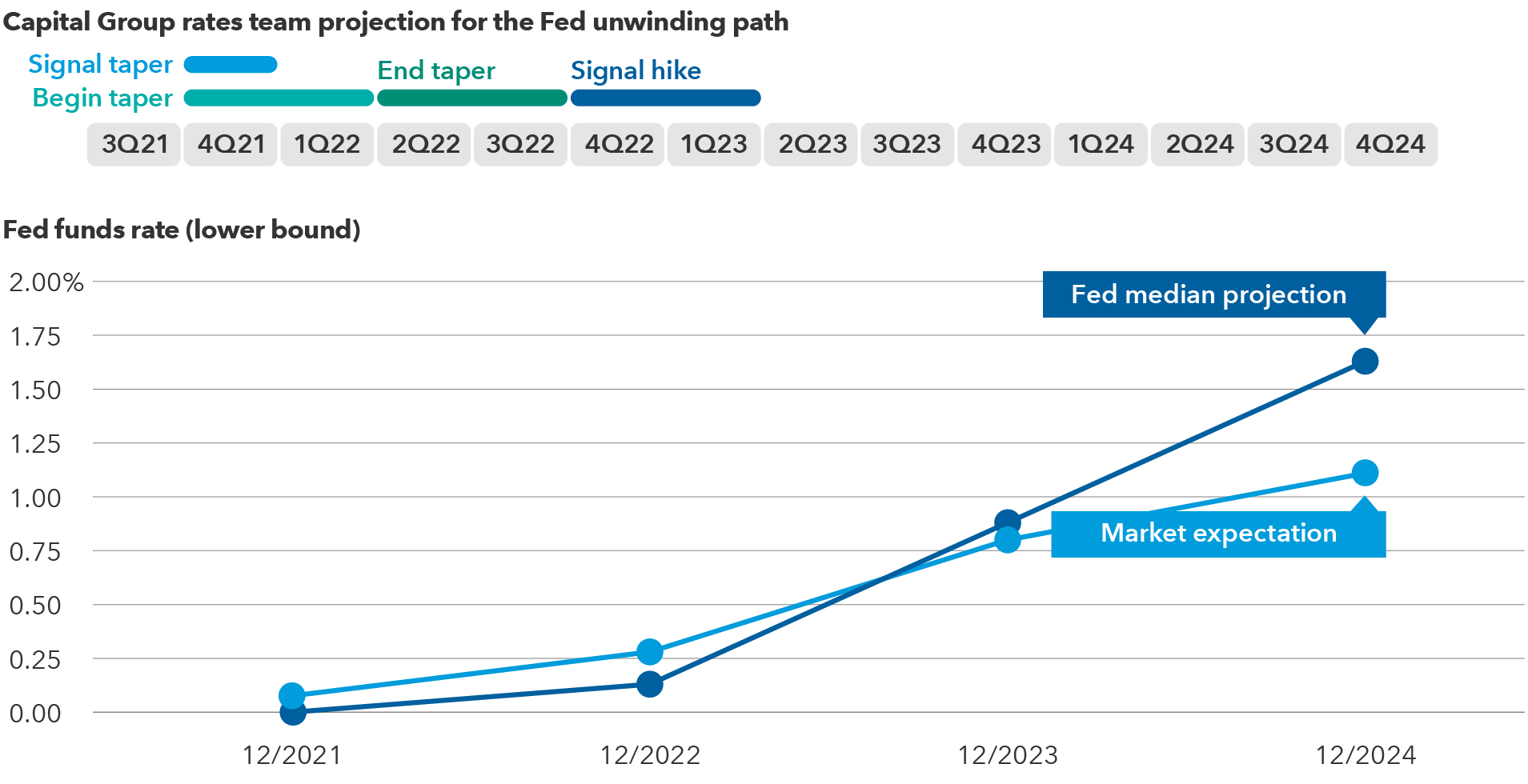

In the final months of this year, we expect the U.S. Federal Reserve to begin scaling back some of the extraordinary stimulus measures launched last year in the early stages of the pandemic. Although the Fed chose not to break any news about its first move at the September 2021 meeting, we already know the initial step. The central bank will begin by reducing, or tapering, the pace of its bond buying.

The last time the Fed tapered, it prompted the infamous Taper Tantrum of 2013. Markets were caught off guard and bond yields soared. With investors better prepared for tightening this time around, we don’t expect another tantrum. The Fed’s unwind has been well telegraphed with only the precise timing unknown. Let’s unpack that path and consider how it might affect fixed income markets.

Fed tapering soon but no hikes likely before late 2022

As recently as August, some investors believed that the Fed could announce the start of its taper program at its September meeting. The relatively weak jobs report paired with a softer inflation rate reading in August closed the door on that possibility, however. We now believe the Fed will announce its intention to taper as soon as its November meeting, unless economic conditions deteriorate significantly before then.

The U.S. central bank will probably begin tapering assets in the weeks following that announcement. Once that begins, based on the Fed’s previous statements and its prior tapering program, we expect it to last roughly six to nine months, most likely ending sometime around the middle of 2022. Currently the Fed is buying $120 billion of U.S. Treasuries and mortgage bonds each month. That amount will decrease gradually until the Fed is no longer adding any securities to increase the size of its balance sheet.

Once the taper has ended, the Fed will only buy assets sufficient to maintain the size of its balance sheet, replacing old securities that mature. At that time, the central bank will consider a three-part test prior to raising interest rates:

- Has the economy achieved maximum employment?

- Has core inflation — the rate that excludes food and energy prices — reached its 2% target?

- Is core inflation on track to exceed its 2% target?

We’ll dig into these conditions next. We believe the Fed isn’t likely to begin considering hiking rates until late 2022 at the earliest. Once it does allow short-term interest rates to drift higher, we expect it to do so in a very gradual manner, as it did from 2015 through 2018.

The Fed’s expected unwinding path: Sequential and gradual

Sources: Capital Group, Bloomberg, Federal Reserve. As of 9/22/2021.

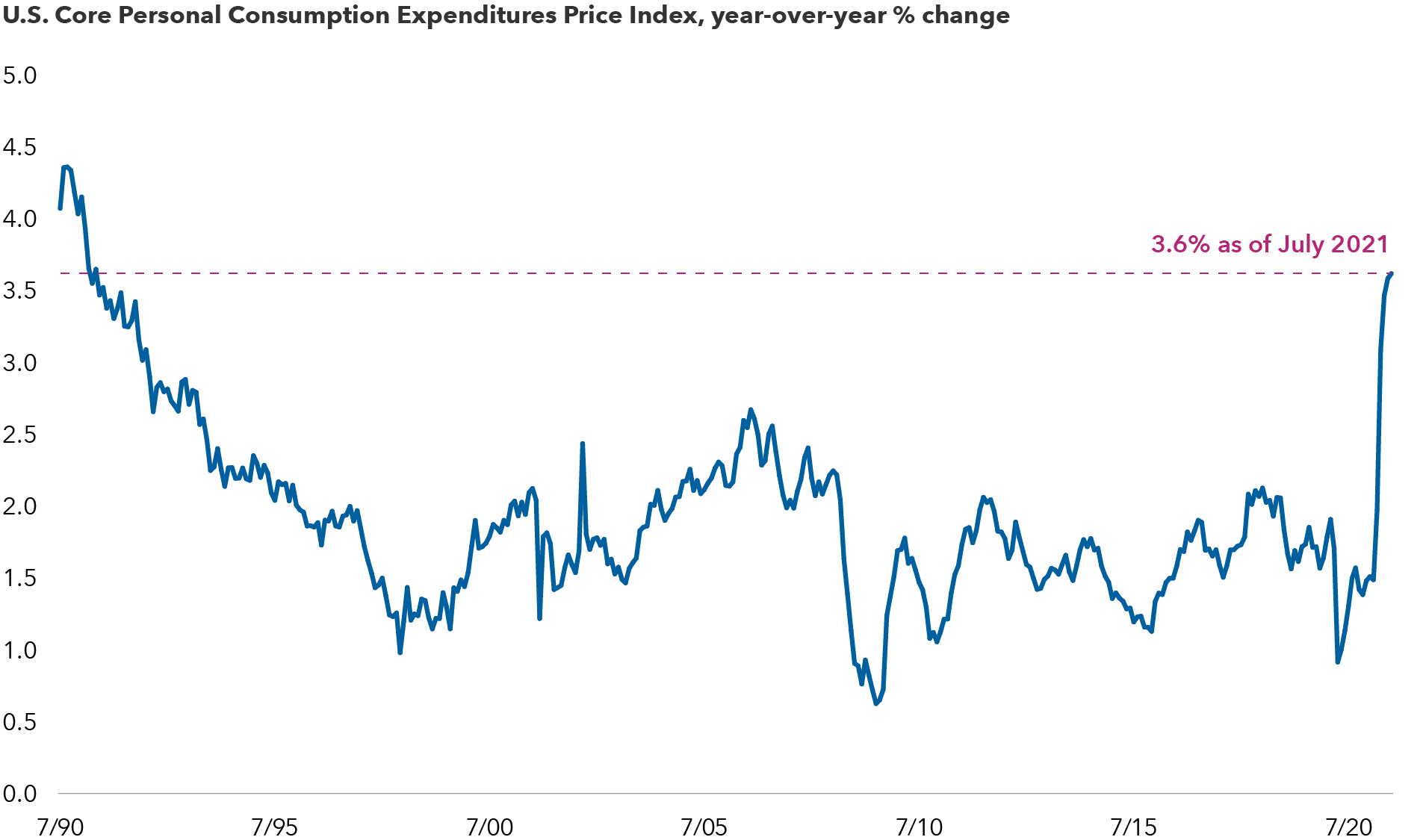

Why the Fed hasn’t hit the brakes, despite rising inflation rate

As most investors are aware, the inflation rate is not holding the Fed back. This year it has risen above the Fed’s 2% target. Consider the Fed’s favored measure, the U.S. Core Personal Consumer Expenditures Price Index. Its July reading was 3.6%. That puts it well above target — at a level not seen since the early 1990s.

Core inflation is the highest in three decades

Source: Bloomberg. As of 7/31/2021. Core inflation excludes food and energy prices.

But today’s inflation rate is not necessarily what matters when it comes to interest rate hikes. The Fed probably won’t begin considering that move until late next year. We’ll have to wait to see if the current high inflation rate is durable enough to last until then. If price growth recedes below its target, the Fed may have to wait longer.

On the other hand, inflation pressures could begin to look more severe. For example, we could see higher prices begin to bubble in areas like rent, housing and services. If the Fed begins to worry more about inflation running too hot, it may feel compelled to respond sooner.

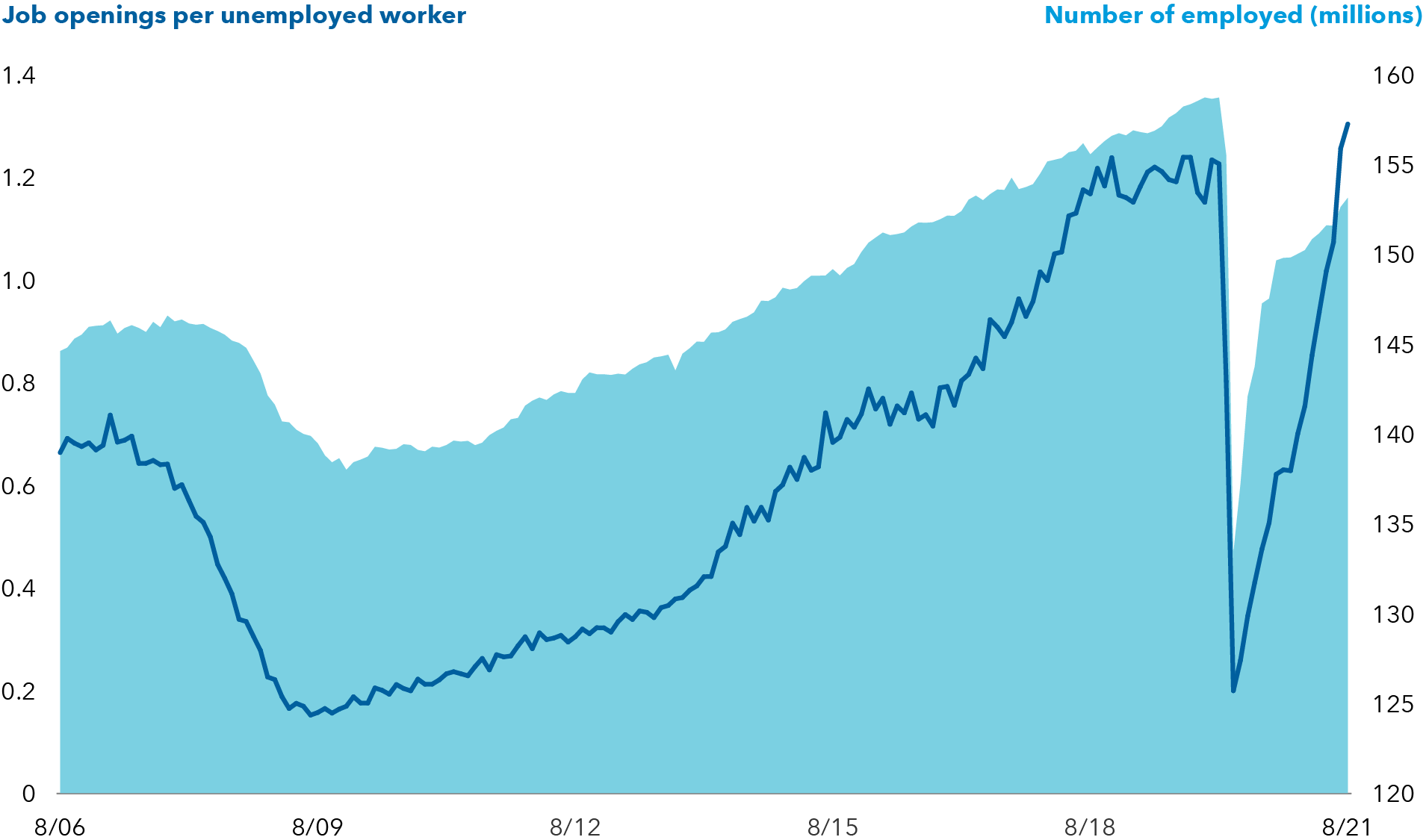

The Fed is unlikely to signal interest rate hikes until there is a clearer employment outlook

Full employment is tougher to measure. Right now, we’re seeing some real dislocations in the labor market. Payroll surveys show the U.S. had 5 million fewer people working this summer than it did in early 2020. And that doesn’t even account for the expected natural growth of 200,000 new workers each month. That widens the gap to at least 8 million fewer workers than full employment would imply.

But looking at wages and job openings complicates this picture. Lower wage workers have seen income gains exceeding 3% this year — well above average. We are also seeing 1.3 job openings for each unemployed worker. These factors would normally indicate a very strong labor market. Current trends paint a murky picture, however. For example, the labor market could look less healthy next year than those job openings and wage increases indicate, delaying the Fed’s first interest rate hike if the unemployment rate needs more time to heal.

Mixed signals: High job openings, low employment

Source: Bloomberg. As of 8/31/2021.

Why we don’t expect Taper Tantrum 2.0

Fixed income investors panicked when the Fed announced its last taper. We don’t expect that this time. First, investors have seen the Fed take such action before. They saw its impact and that broader normalization was far from catastrophic. Back in 2013, investors feared the Fed would eventually increase the federal funds rate from zero to a range of 4% to 5% over time. That didn’t happen. This time they’re not expecting the Fed to hike interest rates much above 2%.

Capital Ideas™ webinars

Insights for long-term success

Second, the market should not be caught by surprise once the process begins. The Fed has been very transparent with its plans. In numerous speeches and other communication, Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell and other governors have explained what to expect. As a result, the market isn’t likely to react as dramatically. Of course tighter financial conditions — through reduced liquidity and higher borrowing costs — will still have some negative impact on investors’ appetite for risk.

The Fed’s clarity has led current bond yields to already reflect the assumption of a taper announcement before the end of the year. After that happens, investors’ concerns will likely shift to how quickly the Fed reduces its asset purchases and when it will start hiking interest rates. If inflationary pressures persist and the labor market trends in the positive direction, we could begin to see Treasury yields rise across the maturity spectrum.

When the Fed begins raising short-term interest rates, shorter term yields may feel a more direct impact, prompting the yield curve to flatten. Historically, this is how we have seen it play out.

While yields throughout the market should rise over time as the Fed normalizes, the past 12 months have shown just how stubborn low yields can be. Concern about the longevity of robust economic growth has been one factor. Investors began to understand the persistence of COVID-19 when Delta and other strains caused new infection surges. The Chinese economy, a source of global economic strength over the past decade, has also been slowing. Lastly, investors believe the Fed’s inflation narrative — that the high rate we’re seeing is just transitory.

Some investors may fret or become nervous about the Fed pulling back. Yet, policymakers will only do so when they’re confident the economy can sustain it. Ultimately, normalization should help ease the concerns about inflation that have cast a long shadow over markets this year. Importantly, once the Fed has trimmed its balance sheet and, eventually, raised interest rates, it will be in a much stronger position to act when the next major economic challenge begins. Looking at the taper through the lens of a Fed that wants to maintain price stability should reassure investors: Core fixed income funds should continue to provide ballast in diversified portfolios.

The U.S. Core Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index provides a measure of the prices paid by people for domestic purchases of goods and services, excluding the prices of food and energy. The core PCE is the Fed's preferred inflation measure.

BLOOMBERG® is a trademark and service mark of Bloomberg Finance L.P. and its affiliates (collectively “Bloomberg”). Bloomberg or Bloomberg’s licensors own all proprietary rights in the Bloomberg Indices. Neither Bloomberg nor Bloomberg’s licensors approves or endorses this material, or guarantees the accuracy or completeness of any information herein, or makes any warranty, express or implied, as to the results to be obtained therefrom and, to the maximum extent allowed by law, neither shall have any liability or responsibility for injury or damages arising in connection therewith.

Our latest insights

-

-

Market Volatility

-

Market Volatility

-

-

Artificial Intelligence

Never miss an insight

The Capital Ideas newsletter delivers weekly insights straight to your inbox.

Timothy Ng

Timothy Ng

Tom Hollenberg

Tom Hollenberg