Markets & Economy

Russia’s military aggression against Ukraine — Europe’s largest ground war in generations — has impacted millions of people and triggered a large-scale humanitarian crisis. From a financial perspective, the February 24 Russian invasion took markets utterly by surprise. The global economy, already reeling from high inflation, suddenly faced dire new threats, including a severe energy shortage, a growing refugee crisis and the potential for a protracted war in eastern Europe.

The conflict also carries wide-ranging geopolitical implications for the future of European cooperation, the changing posture of U.S. foreign policy toward Russia and China, and the reversal of globalization trends that have transformed the world since the end of the Cold War.

What follows are a range of views from across Capital Group’s investment team of political analysts, economists, and equity and fixed income portfolio managers and analysts.

Published March 10, 2022

Conflict highlights need for fiscal pragmatism in Europe

Talha Khan, political economist

The world has changed in a matter of weeks, with geopolitical and economic consequences that will reverberate for years to come. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine marks the end of an era of relative stability and peace since the fall of the Berlin Wall and opens a period of geopolitical peril.

Putin crossed the Rubicon once he decided to invade, but he seems to have badly misjudged both the resistance the Russian forces would face as well as the manner in which the Transatlantic Alliance has come together in pushing back.

He has managed to do in just over a week and a half what Western leaders have failed to do in over three decades of painstaking progress on European cohesion. However, we need to be careful in assessing how this conflict ends. In my mind, Ukraine is not going to retain the territorial borders it had before the invasion, and the world will not return to the status quo. Even if Putin backs down, we're likely to see lasting structural changes.

On fiscal policy, I expect greater flexibility for the foreseeable future. It appears the EU’s fiscal rules will be suspended for another year at least. And I believe the debate over revising the fiscal framework will take greater urgency. The threat from Putin's Russia has also highlighted the need to shore up military and energy security. Years of underspending on defense means that European countries are far behind where they should be and need to invest a lot more. So far, Germany is the most prominent example of this shift in thinking.

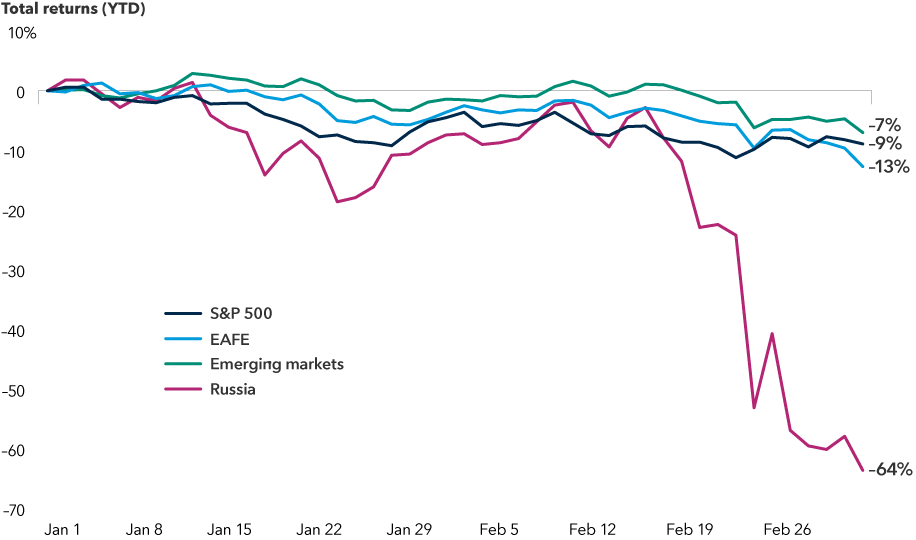

Pandemic, inflation, war; It's been a tough start to the year

Sources: MSCI, RIMES, Standard & Poor's. As of 3/4/22.

Sanctions pose a dilemma for EU policymakers

Robert Lind, European economist

This week, the U.S. announced expanded economic sanctions against Russia, banning imports of oil and gas, and the U.K. quickly followed suit, banning Russian oil. But the EU, which counts on Russia for a significantly larger portion of its energy supply, has not moved as forcefully, vowing only to cut its gas imports by two thirds within a year.

A full energy embargo on Russia would be extremely painful for the major European economies, especially Germany and Italy and smaller countries in central and eastern Europe that depend on Russian gas imports. In the short term, the EU should be able to cope with offsetting imports of LNG. But the bigger challenge will come during the summer when gas is being stockpiled for winter. Higher prices will make it even harder.

Analysis by the European Central Bank (ECB) and others show that a significant reduction in gas supply would have substantial negative effects on the euro zone’s GDP. For instance, the ECB estimates a 10% reduction would reduce euro zone GDP by around three quarters of a percentage point. Given that Russian imports account for around 40% of EU gas supply, an energy embargo could depress GDP by 3% to 4% relative to the pre-war baseline.

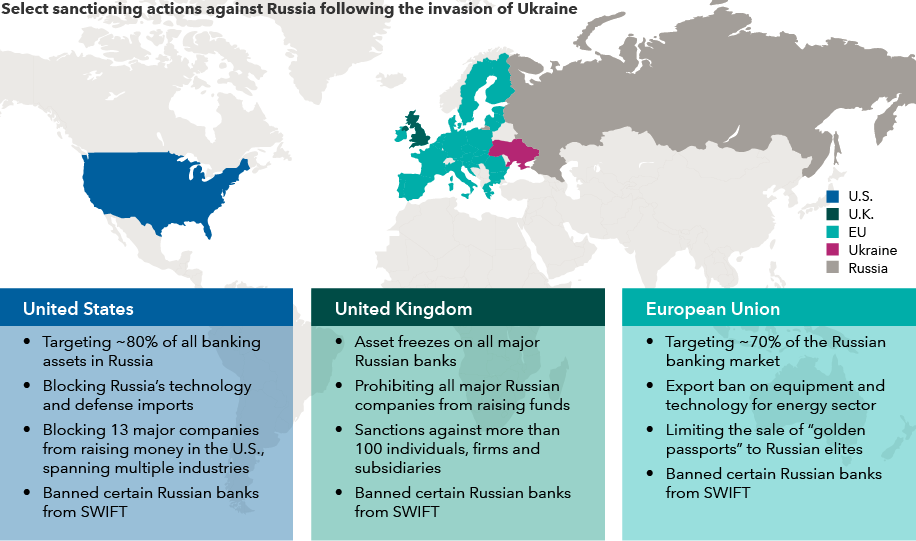

International sanctions are mounting against Russia

Sources: Capital Group, Council of the European Union, U.K. Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, U.S. Department of the Treasury, U.S. State Department. As of March 7, 2022. Note: SWIFT is the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication, which runs a messaging and payment system used by more than 11,000 financial institutions. “Golden passports" refer to residence permits that can be made available to foreign nationals and their immediate family via certain citizenship-by-investment programs.

Unsurprisingly, the EU is wary of implementing sanctions that could have such a damaging impact on its economy. But if the recent spike in oil and gas prices continues or is protracted, the European economy will suffer a negative supply shock even if there is no embargo. Alongside steep energy prices, we are seeing higher prices for other commodities related to the global food supply chain. Prices are also rising sharply for fertilizer and building materials. At the same time, in the absence of an embargo, higher energy prices will boost Russia’s export earnings, mitigating the effects of the economic and financial sanctions.

In the light of extreme uncertainty, I expect the ECB to avoid giving a clear signal that it will end its asset purchases. It will also have to closely monitor the inflationary shock this conflict brings. There is a growing risk of stagflation in Europe, which is a bigger challenge. Central banks would want to monitor any signs of inflation expectations so they don’t fall behind. I think they will continue to signal a removal of monetary accommodation, but at a much more cautious pace.

Gas is more challenging than oil for Europe’s economy

Craig Beacock, equity investment analyst

There’s an important distinction between oil and gas that seems likely to impact Europe and could ripple through the global economy, given the region’s heavy manufacturing and industrial base for automobiles, airplanes and chemicals. Oil is relatively easier to supply and ship around the world when there are supply disruptions in certain regions. Natural gas, on the other hand, is much less fungible. It is far more difficult to transport, whether it is through pipelines or LNG liquefaction infrastructure. So, if Russian supply is significantly curtailed and Europe faces major shortages, it would be challenging to secure replacement supplies. This would be a blow to Germany, which is a large user of gas for power generation.

In the commodities market, oil and gas prices have reacted very differently. While oil prices usually dominate headlines, the spike in gas prices has been more staggering. For example, European natural gas prices recently skyrocketed to trade at roughly the equivalent of $100 per million cubic feet of gas. That’s roughly equivalent to $600 for a barrel of oil. This underscores the disparity in how these commodities are transported around the world.

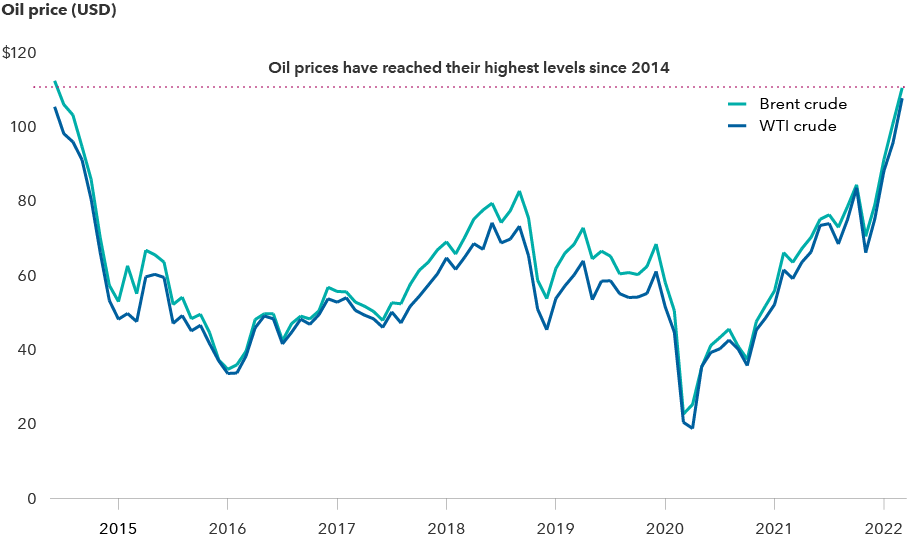

Energy prices spike amid Russia-Ukraine conflict

Source: Refinitiv Datastream. As of 3/4/22.

I expect CEOs of oil companies and others in the industry to play a role in helping to alleviate this global crisis. In the U.S., I anticipate production to grow between 500,000 to one million barrels a day. Trading prices for oil have recently climbed to nearly $140 a barrel. That’s too high. I don’t think the oil producers want prices at this level because it creates volatility and destroys demand. In my view, most oil stocks are being priced for the commodity to trade in the range $60 to $70 a barrel.

I do not expect this to significantly derail the world’s shift to green energy, but I do think it shows how the policy lines around energy security and sustainability could change, especially in Europe. Going forward, I expect policymakers will focus more on a dual mandate. I believe they will put a much greater emphasis on balancing the environmental side of things with the social ramifications of what could happen if they do not shore up energy security and make sure that they have the right supplies from the right partners.

Prior to the invasion of Ukraine, equity markets had been signaling to oil companies a preference for dividends and buybacks and less investment in pumping oil, partly because many projects over the past decade had poor returns on capital. Oil companies have ample cash flow, and if capital expenditures are increased, they should still have sufficient funds to cover both dividends and share buybacks.

Calibrating fixed income investments in this new world

Rob Neithart, fixed income portfolio manager

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is a geopolitical and economic shock, no doubt. Rising commodity prices will feed into inflation and act as a dampener on global growth. That said, we have entered this period with an upswing towards growth in many economies.

The United States was leading the growth recovery mainly because its fiscal and monetary policy actions have been so supportive. On the other hand, China has been working hard to slow things down and tighten financial conditions. Europe was somewhere in between — recovering but not as strongly. And finally, there is a wide dispersion across emerging markets, with many economies just beginning to see a post-COVID recovery.

Given this backdrop, our fixed income team is of the view that in the U.S., the Federal Reserve will largely stay on its path of lifting interest rates to contain inflationary pressures as labor markets remain strong and economic growth prospects are modest but positive. Our fixed income portfolios generally favor a short duration stance, especially in the three- to five-year part of the yield curve. Longer term interest rates are likely to remain anchored by investors seeking the safety of U.S. government debt. The Fed has signaled that inflation momentum is fairly entrenched in the U.S., and with these shocks, it could become even more so. The central bank still has a way to go before financial conditions are considered tight. So, in absolute terms, we're still looking at sharply negative real interest rates.

In Europe, the European Central Bank may take a more cautious approach given Europe’s greater exposure to Russia’s economy and its dependence on Russia for gas.

In emerging markets debt, risk premiums have adjusted, and we are seeing very high yields across the universe — somewhere in the 7% to 8% range in U.S. dollar terms. Despite the extremely severe situation in Russia and Ukraine, most emerging markets have continued to function well, maintaining continued liquidity. Investors that have a longer time frame will probably see very good returns, even though short-term volatility may be significant.

Our fixed income team still favors local currency emerging markets debt given valuations and where many of these credits are in the economic cycle. Many emerging markets have continued to function in a way that resembles developed markets.

Russian and Ukrainian debt markets are a different story. Before the invasion, Russia had one of the strongest credit profiles in emerging markets. It is not financially dependent on external debt markets and was a net creditor — meaning its hard currency assets vastly exceeded its liabilities. Russia had issues with its slow-growing economy, but the financial strength of its balance sheet had always been a positive. Ukraine, on the other hand, was an improving credit and taking policy actions that looked positive for the credit over the long term. It had moderate levels of debt, and it did not appear to be in a situation where financial sustainability was in question.

Now, obviously, everything has completely changed. Russian debt markets are priced for certain default. Ukrainian bonds are priced higher, but they're still at a default level. There is no market making in these investments, partly due to sanctions.

There are scenarios where markets might begin to function, even in the midst of sanctions. There might be peer-to-peer trading that gets set up, as happened after the invasion of Crimea in 2014. It is unlikely this would facilitate any significant change in liquidity, but it would help with price discovery.

China is likely to accelerate development of import substitution

Victor Kohn, equity portfolio manager

We are looking at the potential impact of these developments across emerging markets and broader capital markets. Clearly, the fallout related to oil and gas and commodities more broadly is significant. Net commodity-exporting countries like Indonesia will be beneficiaries, while countries with a large oil import bill such as India will face challenges. Russia and Ukraine have been major exporters of agricultural commodities such as wheat and precious metals such as titanium. For example, by some rough estimates, about a third of the world’s titanium comes from Russia.

Beyond commodities, I think this will accelerate the trend towards lesser dependence on cross-border sourcing for critical supply chain components. I believe countries will look to increase domestic production where they have capabilities. This will be particularly true for China.

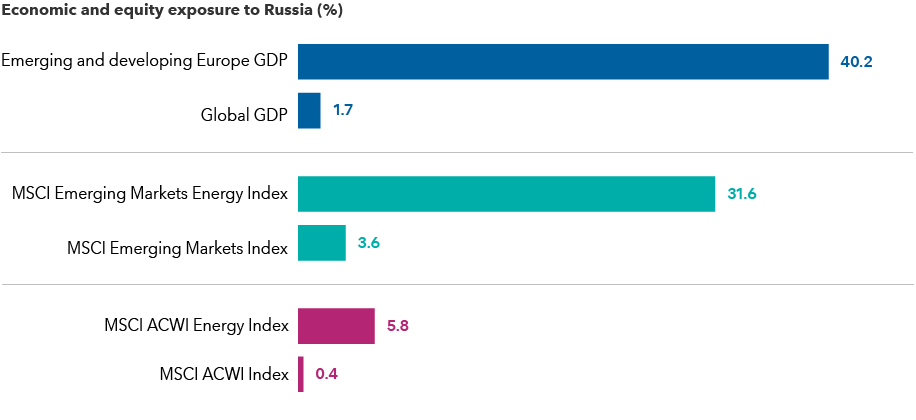

Exposure to Russia looms large for Europe, less so for the world

Sources: Capital Group, IMF World Economic Outlook, MSCI, RIMES. As of December 31, 2021. GDP figures are annual. "Emerging and Developing Europe" includes Albania, Belarus, Bosnia, and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Hungary, Kosovo, Moldova, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Poland, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Turkey and Ukraine. Exposure to equity indexes reflects the percentage of index market value represented by Russion companies within listed indexes.

The invasion of Ukraine and subsequent sanctions by Western nations will potentially be a further catalyst for China’s party leadership to accelerate the country’s domestic capabilities in areas such as technology, pharmaceuticals and consumer-related products. They could also seek to secure energy and metal sources.

China is likely to increase financial support for its leading domestic companies to develop a more localized supply chain that relies less on foreign multinationals. It had already been making this transition in its dual circulation strategy. It took on greater urgency after the U.S. banned telecommunications giant Huawei in 2019 and pressed other countries to do the same.

Across markets, I will be looking to see which companies could benefit from import substitution and which could be challenged — and accordingly adjust portfolios.

The West is united

John Emerson, political economist and former U.S. ambassador to Germany

The transatlantic alliance has not been this united since the aftermath of 9/11. It’s quite remarkable how, after years of skepticism and finger-pointing — whether it was over NATO funding, the imposition of sanctions after Russia began the Ukraine war back in 2014, Brexit or the Trump administration’s America First agenda — Europe and the United States have quickly come together in response to Russian President Vladimir Putin’s unprovoked war in Europe.

For more than two decades, the U.S. has unsuccessfully urged Germany to ramp up its defense budget, kill the Nord Stream 2 pipeline and reduce its energy dependence on Russian gas. Yet, within 72 hours of Russia commencing its invasion of Ukraine, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz signaled a radical shift in multiple sacred pillars of German foreign policy: defense spending will quickly exceed 2% of German GDP, including an immediate €100 billion infusion; German-made weapons can now be sent to Ukraine; and Nord Stream 2 has been halted.

Historically neutral Switzerland has stunningly agreed to adopt all European Union (EU) sanctions against Russia, including freezing Russian funds in Swiss banks. Even traditional supporters of Russia, such as Miloš Zeman, president of the Czech Republic, have condemned the attack on Ukraine and called for harsh sanctions.

We should anticipate significant Russian retaliation for these unprecedented sanctions. This could include severely reducing or even cutting off oil and gas exports to sanctioning nations, as well as restricting exports of titanium and other critical metals. While curtailing oil and gas sales to sanctioning nations would deprive Russia of needed revenue, China would presumably fill some of that gap — at fire sale prices. Moreover, Putin has used the time since the imposition of Western sanctions in response to his annexation of Crimea in 2014 to build up Russian cash reserves and enhance Russian resilience.

Furthermore, we should prepare for the possibility of major cyberattacks on European and U.S. communications, energy and financial systems.

The Germans are preparing for a reduction of Russian gas exports, making plans to backfill with imports of liquid natural gas (LNG). This will be complicated by Germany’s failure over the past several years to complete construction of regasification facilities at its North Sea ports. There is little doubt that energy costs in Europe are likely to skyrocket, which are expected to be inflationary and dampen growth.

All that being said, Putin clearly miscalculated on two fronts: First, the fact that the West would come together as quickly as it did, despite European reliance on Russian energy, the newly elected government in Germany, and potentially distracting domestic challenges faced by U.S. President Joe Biden, U.K. Prime Minister Boris Johnson and French President Emmanuel Macron. Second, Putin miscalculated the intensity of Ukrainian resistance from both the military and civilians.

Notwithstanding all that, sadly, in the end, I think we could end up with an ugly “peace,” with Russia expanding its control over eastern Ukraine after having severely damaged the country’s national infrastructure. It is hard to see how Putin backs down at this point, absent massive domestic opposition within Russia. I expect this war will get worse before it gets better.

U.S. economy faces heightened inflation risk

Darrell Spence, U.S. economist

While the threat to Europe’s economy is far greater, the U.S. economy probably won’t emerge from this conflict unscathed. Rising energy prices were a problem prior to the invasion of Ukraine, and now are moving higher as global markets contemplate a world without Russia’s vast oil and gas supplies.

That could very well lead to higher U.S. inflation, which is already running hot. Price increases for food, energy, and other goods and services essentially rob U.S. consumers of their purchasing power. That can put a damper on consumer spending, which accounts for about 70% of U.S. economic activity.

Could it be bad enough to push the U.S. into recession? I’d put the chances at 25%–30% by late 2022 or early 2023. The R word is a much bigger issue for Europe, of course, because of its proximity to the crisis and dependence on Russian trade, particularly in the energy sector. Europe is more exposed than the U.S., but both economies could falter if the conflict isn’t resolved soon.

With the Fed poised to raise interest rates later this month, some market participants are wondering if the Ukraine crisis might give Fed officials a reason to keep rates near zero. I don’t see it happening.

The Fed is in a tough spot. With U.S. inflation hitting a 40-year high of 7.5% in January — and a war-related energy shock potentially pushing it even higher — Fed officials have no choice in my view but to raise rates at their March 15–16 meeting. In an ideal world, they could pause. But at this level of inflation, I don’t believe they have the luxury. That said, the conflict probably means a hike of 50 basis points is off the table. Rather, a more moderate increase of 25 basis points is likely.

Fed officials have clearly telegraphed their intention to tighten monetary policy. Investors should expect them to do so.

Invasion of Ukraine could mark turning point for cybersecurity

Julien Gaertner, equity investment analyst covering cybersecurity

As the war in Ukraine unfolds, cyberwarfare is likely to play a role. I suspect we will be confronted with some incredibly ugly realities that need addressing. My initial assessment is that this will support increased cybersecurity spending in the near term, but it will be more likely a meaningful inflection point for the industry. The Overton window (the range of policies politically acceptable to the mainstream population at a given time) around cyberwarfare as a tool in international relations could open wide and expose incredible weakness in U.S. and EU security.

Most U.S. critical infrastructure assets fail even basic cybersecurity protocols and penetration testing. I feel reasonably good about the U.S.’s large financial institutions’ security and the tech companies, but that’s about it. Energy and utility companies in both the U.S. and Europe have substantially underinvested in cybersecurity, and many companies remain vulnerable.

Against this backdrop I think cybersecurity investments have strong potential. I have been positive on the cybersecurity industry for two reasons: 1) the spending outlook and 2) the fundamental change in industry structure that allows for platform formation and hence more sustainable growth.

In the short term, I think accelerating cybersecurity budgets among corporations, and federal and state governments is a near certainty. And if the situation in Ukraine escalates, I think there is a chance for much more pronounced long-term changes.

The single biggest change could be a substantially different regulatory environment. Federal and state laws could become extremely prescriptive about minimum cybersecurity standards, especially in industries that are relevant to national security or impact the public. We could see an enormous investment cycle, specifically in the energy and utility sectors. In Europe as well, we could see a massive cybersecurity investment cycle and possibly an acceleration in cloud migrations.

The market indexes are unmanaged and, therefore, have no expenses. Investors cannot invest directly in an index.

MSCI EAFE (Europe, Australasia, Far East) Index is a free float-adjusted market capitalization-weighted index designed to measure developed equity market results, excluding the United States and Canada.

MSCI All Country World Index (ACWI) is a free float-adjusted market capitalization-weighted index designed to measure equity market results in the global developed and emerging markets, consisting of more than 40 developed and emerging market country indexes.

MSCI Emerging Markets Index is a free float-adjusted market capitalization-weighted index designed to measure equity market results in the global emerging markets, consisting of more than 20 emerging market country indexes.

MSCI Russia Index is designed to measure the performance of the large- and mid-cap segments of the Russian market.

MSCI ACWI Energy Index is designed to measure results of large- and mid-cap energy securities from 23 developed markets and 25 emerging markets.

MSCI Emerging Markets Energy Index is designed to measure results of large- and mid-cap energy securities from 25 emerging markets countries.

Standard & Poor’s 500 Composite Index is a market capitalization-weighted index based on the results of approximately 500 widely held common stocks.

MSCI has not approved, reviewed or produced this report, makes no express or implied warranties or representations and is not liable whatsoever for any data in the report. You may not redistribute the MSCI data or use it as a basis for other indices or investment products.

Standard & Poor’s 500 Composite Index (“Index”) is a product of S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC and/or its affiliates and has been licensed for use by Capital Group. Copyright © 2022 S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, a division of S&P Global, and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved. Redistribution or reproduction in whole or in part is prohibited without written permission of S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC.

Our latest insights

-

-

Emerging Markets

-

Global Equities

-

Economic Indicators

-

RELATED INSIGHTS

-

-

Global Equities

-

Economic Indicators

Don’t miss out

Get the Capital Ideas newsletter in your inbox every other week

John Emerson

John Emerson

Talha Khan

Talha Khan

Darrell Spence

Darrell Spence

Craig Beacock

Craig Beacock

Rob Neithart

Rob Neithart