Market Volatility

Market Volatility

It’s déjà vu all over again. With inflation higher than it has been since the 1970s, interest rates rising and the economy slowing, many have grown fearful of investing.

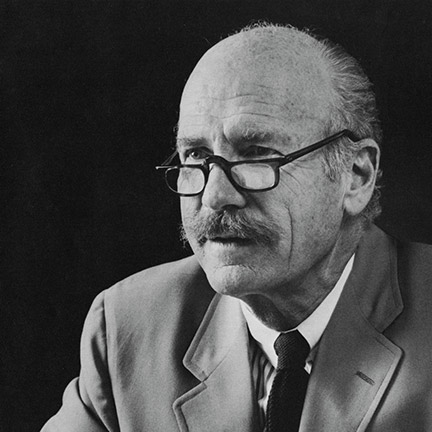

The last time it felt this way was the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. I remember sharing with my colleagues a classic speech from former Capital Group chairman Jim Fullerton. This speech, delivered in November 1974 amid a prolonged bear market, provided us with much-needed historical perspective and a dose of optimism when it was in short supply.

The “Fullerton letter” as it has come to be known, has been recirculated among Capital Group’s investment team at least five times in my career. My former colleague, retired equity portfolio manager Claudia Huntington, shared it in 1987, saying, “I have been saving this speech, one of my favorites, for a time like today.”

I think it’s been shared so often because Jim captured so well what we all know: It is always darkest before the dawn. Over time, and in time, the financial markets have demonstrated a remarkable ability to anticipate a better tomorrow even when today’s news feels so bad.

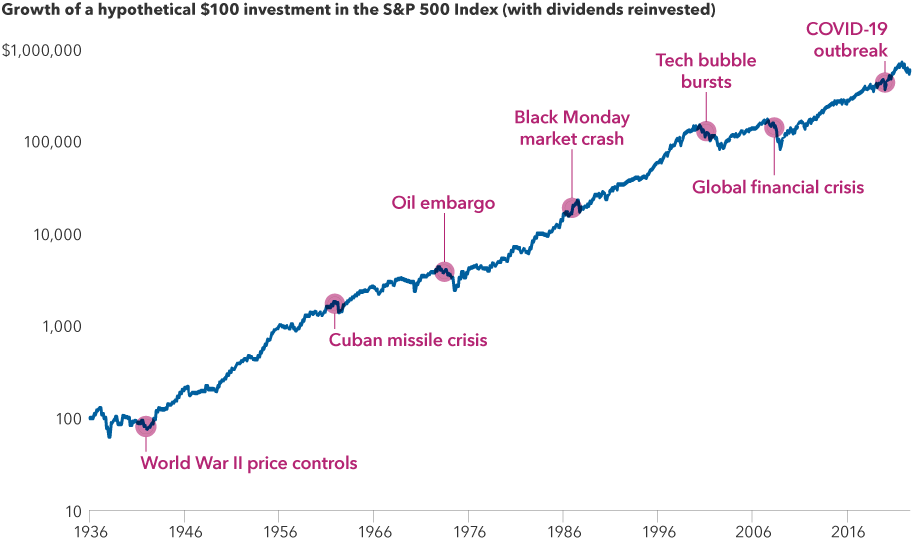

The stock market has overcome past bear markets and unsettling news

Sources: RIMES, Standard & Poor’s. As of October 31, 2022. Chart shown on a logarithmic scale. Past results are not predictive of results in future periods.

We are once again in uncertain territory. It feels scary and terrible. It is exactly those feelings that make this speech so timeless. It’s precisely when the backdrop has looked so difficult that the markets have begun to recover. It’s hard to know when that turn will happen this cycle. But, based on prior experiences the market will turn eventually — and that should provide some solace.

In November 1974, few people thought it was a good time to invest. The Dow had lost more than 40% from its high in January 1973. In his letter, Fullerton recalled an even darker period in our nation’s history — April 1942. His remarks follow, and you can download a copy of the letter:

“We have been here before”

One significant reason why there is such an extreme degree of bearishness, pessimism, bewildering confusion, and sheer terror in the minds of brokers and investors alike right now, is that most people today have nothing in their own experience that they can relate to that is similar to this market decline.

My message to you, therefore, is: “Courage! We have been here before. Bear markets have lasted this long before. Well-managed mutual funds have gone down this much before. And shareholders in those funds and we the industry survived and prospered.”

I don’t know if we have seen the absolute bottom of this prolonged bear market, (although I think we’ve seen the lows for a lot of individual stocks).

Each economic, market and financial crisis is different from previous ones. But in their very difference, there is commonality. Namely, each crisis is characterized by its own new set of nonrecurring factors, its own set of apparently insoluble problems and its own set of apparently logical reasons for well-founded pessimism about the future.

Today there are thoughtful, experienced, respected economists, bankers, investors and businessmen who can give you well-reasoned, logical, documented arguments why this bear market is different; why this time the economic problems are different; why this time things are going to get worse — and hence, why this is not a good time to invest in common stocks, even though they may appear low.

Today people are saying: “There are so many bewildering uncertainties, and so many enormous problems still facing us — both long and short term — that there is no hope for more than an occasional rally until some of these uncertainties are cleared up. This is a whole new ballgame.”

A whole new ballgame

In 1942 everybody knew it was a whole new ballgame. And it sure as hell was. Uncertainties? We were all in a war that we were losing. The Germans had overrun France. The British had been thrown out of Dunkirk. The Pacific Fleet had been disastrously crippled at Pearl Harbor. We had surrendered Bataan, and the British had surrendered Singapore. The U.S. was so ill-prepared for a war that the cavalry school at Fort Riley was still teaching equitation, and I would guess that probably 75% of our field artillery was equipped with horse-drawn, French 75mm guns, Model 1897 (including the battalion in which I was then serving).

In April 1942, inflation was rampant. A Federal Reserve bulletin stated: “General price increases have become a grave threat to the efficient production of war materials and to the stability of the national economy.”

Today there is concern about the slump in housing construction. On April 8, 1942, the lead article in the Journal was: “Home construction. Total far behind last year’s; new curbs this week to cut further … Private builders hard hit.”

Today almost every financial journal or investment letter carries a list of reasons why investors are standing on the sidelines. They usually include (1) continued inflation; (2) illiquidity in the banking system; (3) shortage of energy; (4) possibility of further outbreak of hostilities in the Middle East; and (5) high interest rates. These are serious problems.

But on Saturday, April 11, 1942 (remember when the exchanges were open on Saturday?), The Wall Street Journal stated: “Brokers are certain that among the factors that are depressing potential investors are, (1) widening defeats of the United Nations; (2) a new German drive on Libya; (3) doubts concerning Russia’s ability to hold when the Germans get ready for a full-dress attack; (4) the ocean transport situation with the United Nations, which has become more critical; and (5) Washington is again considering either more drastic rationing with price fixing or still higher taxes as a means of filling the ‘inflationary gap’ between increased public buying power and the diminishing supply of consumer goods.” (Virtually all of these concerns were realized and got worse.)

On the same day, discussing the slow price erosion of many groups of stocks, a leading stock market commentator said: “The market remains in the dark as to just what it has to discount. And as yet, signs are still lacking that the market has reached permanently solid ground for a sustained reversal.”

Yet on April 28, 1942, in that gloomy environment, in the midst of a war we were losing, faced with excess profits taxes and wage and price controls, shortages of gasoline and rubber and other crucial materials, and with the virtual certainty in the minds of everyone that once the war was over we’d face a post-war depression in that environment, the market turned around.

A return to reality

What turned the market around in April of 1942?

Simply a return to reality. Simply a slow but growing recognition that despite all the bad news, despite all the gloomy outlook, the United States was going to survive, that strongly financed, well-managed U.S. corporations were going to survive also. The reality was that those companies were far more valuable than the prices of their stocks indicated. So, on Wednesday, April 29, 1942, for no apparent visible reason, investors again began to recognize reality.

The Dow Jones Industrial Average is not reality. Reality is not price-to-earnings ratios and technical market studies. Symbols on the tape are not the real world. In the real world, companies create wealth. Stock certificates don’t. Stock certificates are simply proxies for reality.

Now I’d like to close with this:

“Some people say they want to wait for a clearer view of the future. But when the future is again clear, the present bargains will have vanished. In fact, does anyone think that today’s prices will prevail once full confidence has been restored?”

That comment was made 42 years ago by Dean Witter in May of 1932 — only a few weeks before the end of the worst bear market in history.

Have courage! We have been here before — and we’ve survived and prospered.

The S&P 500 Index is a market capitalization-weighted index based on the results of approximately 500 widely held common stocks.

The S&P 500 Index (“Index”) is a product of S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC and/or its affiliates and has been licensed for use by Capital Group. Copyright © 2022 S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, a division of S&P Global, and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved. Redistribution or reproduction in whole or in part is prohibited without written permission of S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC.

Our latest insights

-

-

Markets & Economy

-

-

Market Volatility

-

Market Volatility

Don’t miss out

Get the Capital Ideas newsletter in your inbox every other week

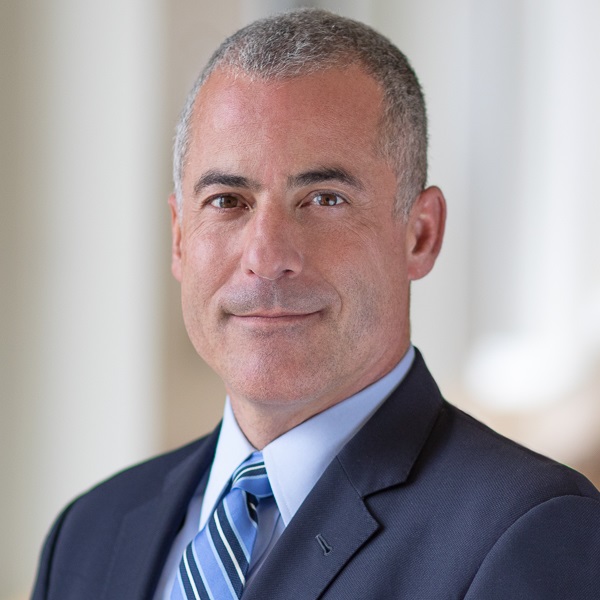

Martin Romo

Martin Romo

Jim Fullerton

Jim Fullerton