U.S. Equities

A thought ran through my head as I stood on a crowded New York City commuter train last October and saw no one wearing a mask: COVID is over. But as one who manages an investment portfolio for retirement plans, I see the effects of the pandemic everywhere, and I believe we’ll be living with its implications for many years to come. I think of it as the pandemic decade.

The pandemic continues to ripple through different industries, has set economic cycles off-kilter, caused bank failures, and drives many of today’s global conflicts in my view.

Different life cycles for products and systems mean the echoes of COVID-19 could linger for a decade — perhaps even a generation. For instance, the length of a commercial real estate loan is usually 10 years, and business travel has not returned to past levels.

COVID-19 kick-started a roller coaster of booms and busts less correlated to the typical economic cycle. As a result, relying on past economic patterns may be misleading. With that backdrop, here are five thoughts on how I believe the pandemic has affected the investment landscape, and how I’m sizing up implications in portfolios I manage for both growth and dividend-paying equities.

1. Capital floods and droughts have delivered different outcomes

First off, the pandemic produced bouts of capital floods and droughts. They are disruptive and not great for industries. Stability is more profitable than extremes. Capital floods can drown almost every competitor. Conversely, capital droughts can cull weaker companies and leave survivors stronger. Let’s take a look back for some context.

Floods: Think 2020. Some industries grew to maturity quickly out of the necessity to keep the economy afloat and maintain a sense of normalcy in our daily lives. Capital flooded into areas where we needed additional resources, making for an extensive list.

These areas included video conferencing, telehealth, food delivery, housing, construction, home refurnishing, technology tools, PCs, electronics (including iPads and phones), streaming video, digital advertising and video games.

Meanwhile, pharmaceutical and vaccine development efforts jumped when scientists rushed to develop cures for COVID-19, fueled by government subsidies.

In almost every flooded area, firms overhired as a result of strong profits and demand. Rapid expansion ended in disproportionate growth for future demand.

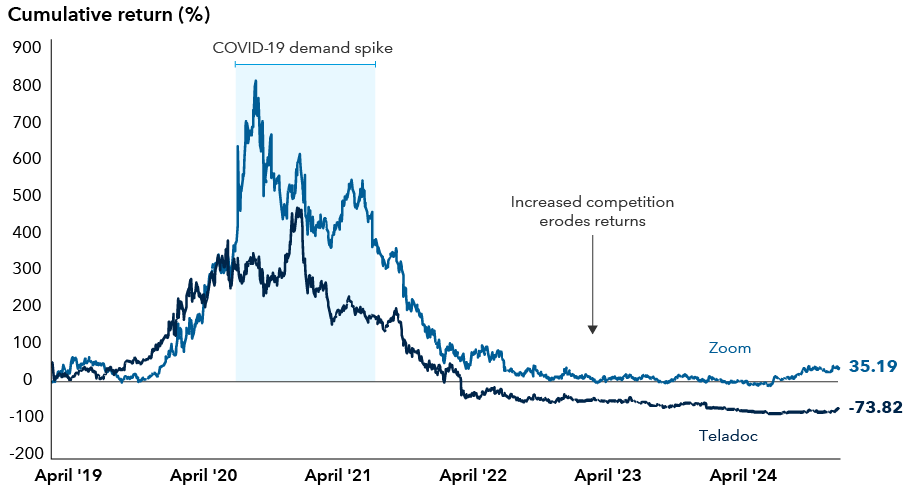

My two favorite examples are Teladoc and Zoom. Both solved a major need when we were working from home. In less than a year, Zoom and Teladoc appreciated 7 times and 2.9 times, respectively, relative to the market. But floods of capital and limited barriers to entry favored other solutions longer term. Today, Zoom stock is worth about the same as it was before the pandemic while Teladoc is worth much less.

Staggering rise, sudden collapse

Source: Factset. Data as of April 22, 2019, to February 14, 2025. Past results are not predictive of results in future periods.

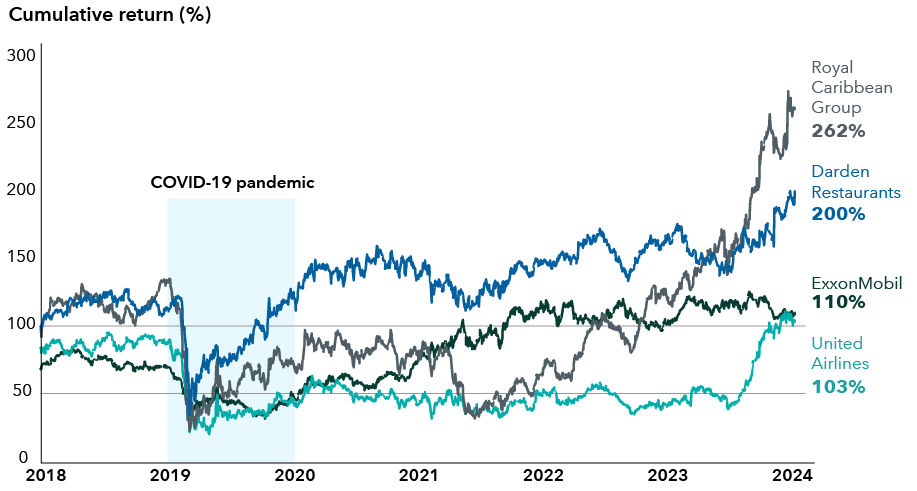

Droughts: In 2020 and 2021, some businesses shrank, lost staff and scale, and they continue to struggle. Yet the strongest companies in these areas are better off and have been solid investments from depressed levels.

Broadly speaking, these affected companies were forced to rationalize their cost structures to survive, which made them more profitable when demand returned. In this bucket, I would put travel-related businesses (airlines, hotels and cruise lines), restaurants, aerospace suppliers, nursing homes and energy providers.

While several industries subject to drought haven’t rebounded enough to beat the market since March 2020, if you had purchased them in the heart of the pandemic, you could have increased your investment two to four times relative to the market.

Slow start, stronger finish

Source: Factset. Returns indexed at 100. Data from December 31, 2018, to February 18, 2025. Past results are not predictive of results in future periods.

The investment implication: Capital floods can create tremendous growth, but you should be wary of competition and ready to sell. Capital droughts might make it easier to realize investment returns because knowing when to sell is less tricky in my view.

2. Rolling recessions are not in sync

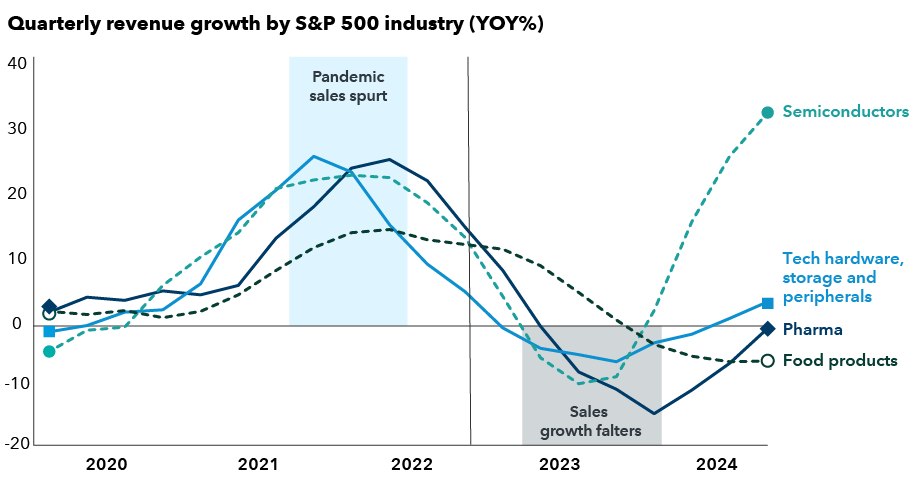

When have we ever seen demand spike concurrently for toilet paper, groceries and personal computers? The pandemic sparked uncommon demand cycles across industries, making for strange bedfellows. Typically, most economic cycles are driven by interest rates and the resulting cost of capital. The COVID-19 cycle was not. Procyclical sectors, like electronics and housing, boomed simultaneously, along with defensive sectors such as consumer staples.

This made for some interesting booms and busts. The reopening of the U.S. economy brought a sharp downturn to analog chips and pharmaceutical R&D. Yet the echoes of these cycles, like the shifting of chip allocations away from cars, resulted in an auto shortage a year later.

Sales accelerated during the pandemic, then faltered

Source: Factset. Pharma = S&P 500 Pharmaceuticals Index. Tech hardware, storage & peripherals = S&P 500 Technology Hardware, Storage & Peripherals Index. Semiconductors = S&P 500 Semiconductors Index. Food products = S&P 500 Food Products Index. Data from March 2020 through December 2024.

The investment implication: Isaac Newton's third law of motion states, "For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction." Periods of exceptional growth are followed by scarcity. It takes time for industries to equilibrate after a shock.

3. Past economic patterns may be misleading

The pandemic resulted in changes to labor, housing and commercial real estate that could persist for an extended period. While the Federal Reserve did cut interest rates in 2024 after a two-year hiking cycle, we may end up in a period of higher interest rates.

Labor: The labor market remains tight. Early retirements, long COVID and government stimulus shrank the labor pool. Geographic moves created further distance between worksites and workers.

Usually, when the economy is strong and unemployment is low, there are numerous job vacancies. Following the pandemic, we are seeing higher levels of vacant jobs along with higher levels of unemployment, which signifies inefficiency in the labor market, or a mismatch in skills or geography between jobs and workers. You can see evidence of this in the number of help-wanted signs at retail shops and restaurants and in persistent wage inflation.

Geographic change: We’ve never had an economic phenomenon that impacted labor similarly to the pandemic. Within three months, people started moving out of cities and high lockdown areas (California, New York, Pennsylvania, Illinois and Michigan) to more rural, less locked down areas (Idaho, Arizona, Texas, Colorado, Tennessee, Kentucky, Georgia and Florida). This trend continued for three years.

The Great Resignation: “An unprecedented number of U.S. workers quit their jobs in 2021 and 2022 — a phenomenon dubbed the Great Resignation,” the U.S. Census Bureau stated. Some workers exited the labor force. Particularly, workers left food service, construction and nursing.

The investment implication: Labor dynamics are a critical part of the economic cycle. The availability of labor affects economic growth, output and consumption. COVID affected labor in ways that make future economic cycles harder to predict.

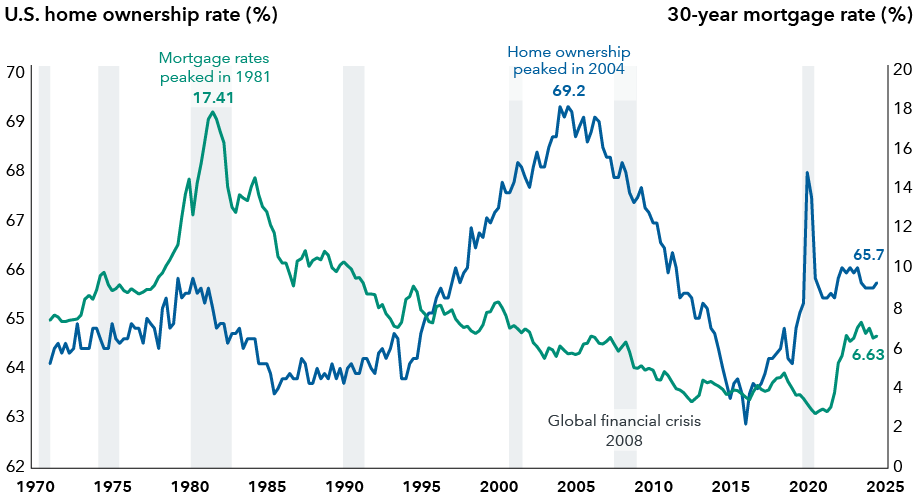

4. Housing: What will be the norm?

We should be careful about expecting the housing market to return to "normal." The pandemic pulled forward U.S. housing demand. It occurred after a long period of low rates helped many finance new homes or refinance existing mortgages.

Three months into the lockdowns, people started moving out of cities, seeking safety, space and a lower cost of living. They moved to bigger houses to accommodate work-from-home and bought second homes as a refuge, freed from office commutes or school drop-offs.

Now, interest rates and construction costs are much higher, and home affordability has fallen. Rates on existing mortgages are well below current rates, so residents are motivated to stay put, not move and hold tight to existing lower rate mortgages.

Housing activity may be focused on renovation in coming years, but projects will be smaller because economic returns are uncertain. Builders, mortgage insurers and credit bureaus are all likely to be impacted to varying degrees.

Home ownership has declined sharply from its 2004 peak

Sources: U.S. Census Bureau, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Data not seasonally adjusted. Data from April 1, 1971, to October 1, 2024.

The investment implication: Housing is a major driver of the U.S. economy. Interest rates, construction labor, material costs and credit availability all factor into affordability. Given the shocks to so many of those inputs, it’s hard to predict where housing starts will settle.

5. Commercial real estate is a shell of its former self

Take a walk through downtown office districts across America and you get a sense the commercial real estate market is a shell of its former self. Available space signs and shuttered restaurants inside towering office buildings are common sights. Overall, the vacancy rate for U.S. office buildings was 21% at 2024 year-end compared with 13% in early 2020, according to real estate broker Cushman & Wakefield.

Getting people back to the office has been a gradual process. Most companies didn’t start calling people back until early 2022. Big business gatherings and conferences didn’t return in force until 2024. And business travel remains below pre-pandemic levels. This year, some large firms have pushed for employees to return to the office five days per week, though we haven’t witnessed broad commitments to such mandates.

The investment implication: Property defaults are a slow-moving freight train. This will continue to flow through banks, investors, lenders and private equity. But it could take up to five more years as debt matures and cannot be repaid or refinanced. If the labor market loosens, companies could regain the leverage to call employees back to offices, but many jobs could remain remote or partly remote indefinitely.

So, where’s the next flood or drought?

There are floods in artificial intelligence (AI) and GLP-1s. I’d argue that real estate and housing are areas of drought.

AI: We are seeing massive amounts of capital spent for semiconductors, data centers and power development to fuel the use of AI. This extends from leading-edge chip provider Nvidia all the way to private equity funds focused on infrastructure. The continuation of this investment trend will depend on returns generated from the AI applications across industries.

GLP-1s: Eli Lilly’s and Novo Nordisk’s success in cracking the puzzle of safe, effective weight loss drugs have spurred an arms race to develop cheaper and easier-to-administer GLP-1 obesity drugs. According to health care firm IQVIA, there are 124 obesity drugs in development pipelines. Not all will succeed, but many companies are chasing this very large market.

Real estate: Investors’ attention has shifted from commercial real estate to industrial real estate, data centers and multi-family housing. Office vacancies remain high but could trend lower if we see a cultural shift back to working in offices.

Housing: Lower investment in housing due to poor affordability (caused by high construction costs, high mortgage rates and higher insurance costs) has resulted in limited growth. This means fewer people build wealth through home ownership. It may create a labor imbalance by making it hard for people to move to areas with job vacancies. It could push rents higher, lower birth rates, drive migration to lower cost regions and increase homelessness and wealth inequity.

Moving forward

The pandemic clearly had many short-term impacts. It pulled forward many long-term trends already underway, like videoconferencing, telehealth, the demise of onsite retail and the development of some pharmaceutical platforms like mRNA, which carries DNA’s instructions for making new proteins. Short-term impacts could take a decade to cycle through and rebalance into traditional cyclical patterns.

While everyday life has gradually returned to normal following the surge of COVID illnesses and stay-at-home lockdowns, the pandemic continues to ripple through the economy in unconventional ways.

As a long-term investor, I think we need to be more creative in attempting to predict the economic future and investment opportunities given the unique shock we just experienced.

Past results are not predictive of results in future periods.

S&P 500 Index: A market-capitalization-weighted index based on the results of 500 widely held common stocks.

S&P 500 Pharmaceuticals Index: A subset of the S&P 500 Index that tracks the performance of companies in the pharmaceutical sector of the broader S&P 500 Index.

S&P 500 Technology Hardware, Storage & Peripherals Index: A subset of the S&P 500 Index that tracks the performance of companies involved in the technology hardware, storage and peripherals industry.

S&P 500 Semiconductors is a subset of the S&P 500 Index that tracks the performance of companies involved in the semiconductor industry. This includes companies that design, manufacture and sell semiconductor devices and related equipment.

S&P 500 Food Products Index is a subset of the S&P 500 Index that tracks the performance of companies involved in the food products industry.

Don't miss our latest insights.

Our latest insights

-

-

Market Volatility

-

Market Volatility

-

World Markets Review

-

Don’t miss out

Get the Capital Ideas newsletter in your inbox every other week

Cheryl Frank

Cheryl Frank