Municipal Bonds

Taxes

- Tax rules change — be vigilant and stay flexible.

- Diversify your tax strategies to hedge against tax-rule changes.

- Think beyond deductions to long-term goals.

You know that diversification can protect your investment strategy from curveballs thrown by financial markets. But what about your tax strategy?

If there’s one thing to learn from the sweeping tax reforms of 2018, it’s that tax rules change. Despite what many taxpayers believe, tax rules are not “permanent.” The only way to protect yourself from the vagaries of taxation is to diversify your approach.

“Do not put all your eggs in one tax strategy basket,” says Capital Group wealth strategist Jeff Brooks. “We just don’t know what will end up becoming the law and how that law will be interpreted and enforced by the Internal Revenue Service.”

The value of a diversified tax strategy will become clear in April, when the realities of many tax changes that kicked in during 2018 hit home.

Changes made by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 serve as valuable and practical lessons in the need for flexibility. “’Permanent tax laws’ means they are permanent until Congress changes them,” Brooks says.

Here are nine tips for building a diversified tax strategy that can help investors stay ahead of whatever comes out of Washington:

1. Manage standard deductions.

Tax strategies that work well in one year can falter when tax rules change. Flexible strategies allow investors to shift where it makes sense. The 2018 tax year presents several examples.

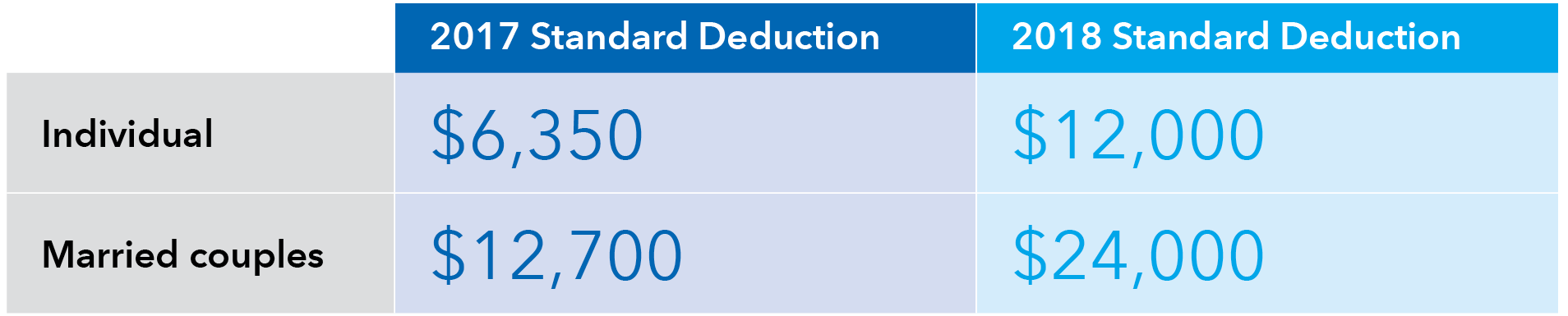

Perhaps the most significant change for many taxpayers in the 2018 tax year is the near doubling of the standard income tax deduction. The deduction jumps from $12,700 to $24,000 for married couples, and from $6,350 to $12,000 for single filers.

This major change means the vast majority of taxpayers will not itemize, Brooks says, which puts into question the usefulness of past strategies that relied on itemized deductions.

2. Consider bunching.

So what should itemizers do now? Brooks suggests crafting a tax plan that “bunches” into a single tax year expenses that previously were deducted annually. For example, taxpayers might take the standard deduction in one year, and then accumulate deductible expenses to itemize for next year.

“If I have deductions I spread over a number of years and would not be in a situation where I could itemize, why don’t I try to force them into one year?” Brooks says.

A donor-advised fund (DAF) is a good option for the charitably minded. A DAF is a centrally managed collection of individually directed charitable accounts. It allows individuals to irrevocably donate cash, stock or other assets like real estate and take a deduction in the year of the gift to the DAF that presumably would be greater than the standard deduction limit.

Donors don’t have to release all the funds to charity at once. “I can keep making gifts year after year from the donor-advised fund, but I get the deduction in the year of my gift to the fund,” Brooks says.

3. Keep an eye out for new opportunities.

It’s also important to refresh tax strategies to take advantage of new incentives. For instance, Qualified Opportunity Funds (QOFs), a tax incentive created in 2017, might appeal to high net worth investors.

QOFs — which can be used to invest in Qualified Opportunity Zones identified by states as needing economic development — can enable investors to postpone and possibly eliminate taxes resulting from the realization of gains on the sale of capital assets. As long as sale proceeds are invested in QOFs for this purpose, taxation of the capital gains is postponed. Over time, the tax basis in the sold property is adjusted, reducing or eliminating the tax generated by the sale, Brooks says.

4. Update estate plans.

The estate tax planning process should never be “set it and forget it.” Changes to estate-planning laws are common and can be significant. Plans built on current rules can be rendered ineffective by subsequent legislative changes.

Take 2018 as an example. The basics remain the same: Lifetime gifts carry cost basis to the recipient, and estate assets receive a “step up in basis” to date of death value at owner’s death. However, the gift and estate tax exemption amounts doubled in 2018 to $11.8 million per individual, or $22.36 for a married couple.

5. Believe in basis planning.

The result? Basis planning is the new paradigm. It’s now prudent for taxpayers to use the much higher exemption amount to keep appreciated assets in their estates, Brooks says. When they die, they can then bequeath appreciated assets to beneficiaries. That way, the basis is stepped up to value at the time of death.

“Now the argument is switched for many more taxpayers who are now saying, ‘No gifts. I want that property included in my estate,’” he says.

6. Pay medical and education costs directly.

For ultra-wealthy taxpayers, the $11.2 million lifetime exception may still be too low. One way to increase their tax-free gift ceiling is to help pay the education and medical expenses of loved ones, Brooks says. Most commonly used for children or grandchildren, these payments may be made for anyone and do not apply to the annual exclusion or lifetime exemption if payment is made directly to the provider. Gifts to newly created and tax-advantaged ABLE accounts are another way to fund lasting care for those with special needs.

7. Use the rules to your advantage.

All tax laws are subject to change, but some have withstood the test of time, Brooks says. Including longstanding statutory structures spelled out in the Internal Revenue Code can make a tax plan more durable.

“These are rules that have been on the books for years,” Brooks says. “If you build something around these, you might have more faith they’re going to remain available for years to come.”

Certain “split-interest trusts,” such as grantor-retained annuity trusts, charitable remainder trusts, charitable lead trusts and qualified personal residence trusts, are structures that have endured and may give investors more faith in their longevity. Consider them not only for their tax benefits but also the protection they may offer from changes to other tax provisions.

8. Negotiate based on tax changes.

Knowing a change is coming is essential when negotiating the terms of an agreement that will carry forward into future tax years. Again, 2018 serves up an important reminder of this. Prior to 2018, alimony was deductible by the payer and reported as income by the recipient.

All that changed for 2019. Alimony payments for divorces finalized after December 31, 2018, are no longer deductible. In essence, alimony payments are now made with after-tax dollars.

The payment amount should reflect the new tax treatment of alimony or support payments. “When negotiating or renegotiating a divorce decree, be certain that it properly reflects the economic consequences of this change in the law,” Brooks says.

9. Diversification pays.

Diversification of tax strategies allows taxpayers to create plans that accommodate changes to the law. The most recent changes have enabled taxpayers to focus less on minimizing their tax bill and more on creating strategic goals to meet current cash flow needs and build a legacy.

“The changes imposed by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act have allowed more people to refocus on the true purpose of charitable and non-charitable giving, rather than simply the creation of a tax deduction,” Brooks says.

Above all, recent changes to the tax code are a reminder of the importance of seeking counsel. “We always encourage our clients to seek tax counsel,” Brooks says. “Good counsel will raise the fact that laws can and do change over time.”

This material does not constitute legal or tax advice. Investors should consult with their legal or tax advisors.

Our latest insights

-

-

-

Emerging Markets

-

Global Equities

-

Economic Indicators

RELATED INSIGHTS

-

Demographics & Culture

-

-

United States

Never miss an insight

The Capital Ideas newsletter delivers weekly insights straight to your inbox.

Statements attributed to an individual represent the opinions of that individual as of the date published and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of Capital Group or its affiliates. This information is intended to highlight issues and should not be considered advice, an endorsement or a recommendation.

Jeffrey Brooks

Jeffrey Brooks