Market Volatility

Interest Rates

- Inflation and interest rates continue to drive market sentiment.

- There should be sufficient slack in the labor market to contain wage growth.

- Long-term bond yields should remain range-bound even as they adjust higher.

- Rate market volatility to remain above recent multi-year lows as major central banks tighten monetary policy worldwide.

As a fixed income investment analyst at Capital Group, Tom Hollenberg has research responsibility for interest rates. He explains why interest rates should remain range-bound, despite rising inflation and tightening by central banks.

Concerns about a rise in inflation and interest rates are driving investor sentiment and market volatility. What are your thoughts?

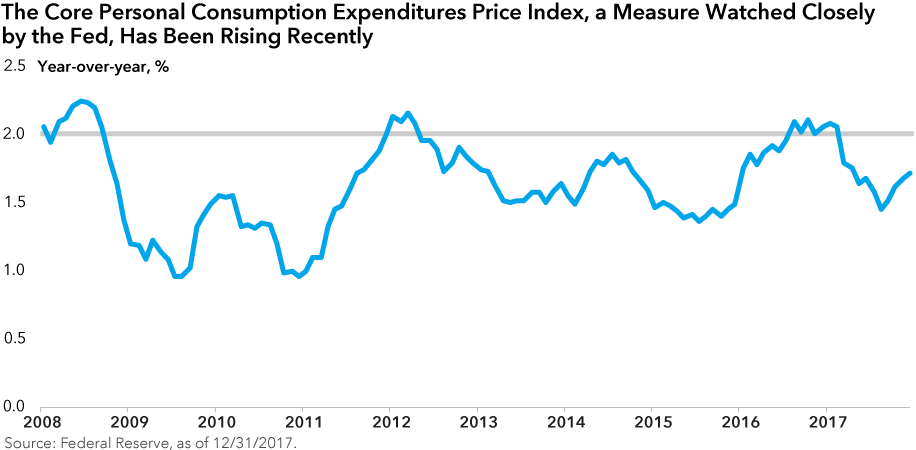

There is no doubt that inflation has turned around pretty remarkably since its period of mid-2017 weakness. We learned on Wednesday that in January the core Consumer Price Index (CPI), which excludes volatile food and energy prices, rose 0.3% month-over-month, which was above expectations. This provides further evidence that we will continue to see a gradual firming of inflation. I expect the core Personal Consumption Expenditure (PCE) Price Index — the Fed’s favored measure that excludes food and energy prices and which generally runs 30 to 40 basis points below CPI — to rise to nearly 2% this year. That should give the Fed the backdrop it needs to hike rates three times over 2018, assuming other factors don’t derail employment or growth.

The January CPI number was boosted by rising prices of some components such as apparel, furniture, and used cars. But it is inflation in the services area that bears watching, as that tends to reflect any tightness in the labor market. On top of continued strength in shelter inflation, Wednesday’s report showed broad-based price pressure in many services components, such as medical care.

A pickup in average hourly earnings was a factor that set off the sharp decline in stocks earlier this month, as investors worry about how this will feed into inflation. Do you see this as a concern?

We have what some would call a white-hot labor market with very low unemployment. But I think there is still some slack in the labor market. As wages go up — particularly for entry-level occupations — you may see more people who have been on the sidelines start to look for employment. We are already seeing that happen. Therefore, I don’t think you will get a step function higher in wages. And it’s part of the reason we have not seen a spike in wages even though we currently have a 4.1% unemployment rate.

The labor market participation rate is still low on a historical basis. A large portion of this can be explained by secular factors, such as demographics or the opioid crisis. But there is still a cohort of marginally attached workers to the economy who could potentially reenter the labor force given the right incentives. The bottom decile of wage earners has seen a near 5% growth in pay over the past year — much more than top earners in percentage terms. That implies that lower skilled labor, which may be able to enter the market more readily, can soak up new entry-level jobs.

If the economy continues to grow around a 2.3% annualized GDP growth rate, wages should continue to move higher, but at a gradual pace. This would be consistent with a gradual rise in core inflation. Finally, increased investment and automation — think self-serve kiosks in retail stores as one example — can act as a buffer against higher wage costs and their pass-through effect on higher inflation.

We have seen a firming up of economic activity and inflation not just in the U.S., but globally. What does this mean for monetary policy?

We are seeing central banks become less accommodative worldwide. As recently as two years ago, it seemed that only the Federal Reserve was taking decisive tightening action. This began in December 2015 with its first rate hike in nearly a decade. After three subsequent rate increases, in October 2017 it began cutting its asset repurchases on maturing securities, effectively shrinking its balance sheet.

In the latter part of 2017 and in 2018, we’ve seen other central banks come forward. The European Central Bank has announced that it will cut its quantitative easing program in half this year. More recent communication from ECB officials hints that the program could end entirely in September or December, and that a rate hike could follow as soon as a matter of months after purchases end. Because the ECB’s quantitative easing program has served as such a prominent buyer of European debt, its absence could have a significant effect on both Euro and global yields.

A part of the ECB’s bullishness comes not only from better growth prospects, but also from stronger inflation expectations. New collective bargaining agreements are helping to push wages up in countries like Germany. And while the Fed’s dual mandate requires it to base U.S. monetary policy on both inflation and unemployment, the ECB policy is based solely on its inflation target. Furthermore, the ECB has a target of below, but close to, 2% — unlike the Fed’s symmetric 2% inflation target.

Across the English Channel, the Bank of England cut rates in August 2016 following the U.K. referendum decision to exit the European Union. Yet, as it became clearer over the following year that the U.K. economy had performed much better than initial consensus expectations, the Bank of England reversed its cut by hiking rates last November. In its most recent meeting this month, policymakers struck an upbeat tone on inflation, which is pushing markets to expect more rate hikes.

Should this tightening of monetary policy — via both rates and a shrinking of central bank balance sheets — result in higher interest rates? Both short-term rates and long-term rates?

As we see a gradual winding down of this period of experimental monetary policy, global yields are beginning to rise. In the U.S., where yields are the highest among major developed markets, rates have increased due to a number of factors beyond the Fed’s influence. Part of the reason for higher longer term yields stems from a rising term premium, which is the additional compensation that investors demand for holding bonds for a longer period of time. I would say we are seeing a re-pricing of term premium rather than expectations of higher interest rates in the short run. Global central banks could be having a significant effect as well, as tighter financial conditions across the world lead to higher rates abroad — which, in our interconnected markets, could spell higher rates in the U.S.

My base case is that short-term rates, including the two-year yield, should rise gradually, absent a major shock to the financial system. That said, given my expectations for modest rises in pay and inflation, I see the 10-year bond yield remaining range-bound, probably around 3% in the near term, unless global growth and inflation appear to be accelerating at an even more rapid pace than currently anticipated. That is still quite low on a historical basis and should continue to support economic growth. Over the longer term, the picture for 10-year yields is less clear. They could rise as Treasury supply rises with bigger deficits from tax cuts and increased spending in Washington. Yields could also fall if the strength of our late-cycle economic expansion begins to fade, or even if we enter a period of relative calm. A number of fixed income buyers — think pension managers, life insurers, and wealth funds — may view higher yields as an opportunity to add to their portfolios.

Against this backdrop, should we expect market volatility to remain elevated?

Yes. Although the gradual unwinding of the Fed’s balance sheet has gone relatively smoothly, we are still in a period where central banks around the world have begun unwinding extremely loose monetary policies, resulting in tighter financial conditions. So market volatility rising from its extremely low levels shouldn’t be surprising. The CBOE’s Volatility Index (VIX) in early January was under 10. That’s remarkably low compared to its historical level of 19 since 1990.

While the levels of 30 and above seen in recent weeks might be at the high end of their long-term range, something closer to their historical average is probably warranted. And since U.S. interest rates are edging higher, it is no surprise that we are seeing greater volatility in equities as well. Moving away from extraordinarily loose financial conditions globally means that volatility loses a key dampener.

What can investors do to protect purchasing power as inflation begins rising to higher rates than we’ve seen in recent years?

Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities provide a good, explicit hedge against rising inflation. They’re pegged against CPI and high-quality government securities. Having a portion of your portfolio’s fixed income allocation in bond funds like our American Funds Inflation Linked Bond Fund® can help to protect you from rising prices.

The return of principal for bond funds and for funds with significant underlying bond holdings is not guaranteed. Fund shares are subject to the same interest rate, inflation and credit risks associated with the underlying bond holdings.

While not directly correlated to changes in interest rates, the values of inflation linked bonds generally fluctuate in response to changes in real interest rates and may experience greater losses than other debt securities with similar durations.

Our latest insights

-

-

Market Volatility

-

Market Volatility

-

-

Artificial Intelligence

Never miss an insight

The Capital Ideas newsletter delivers weekly insights straight to your inbox.

Statements attributed to an individual represent the opinions of that individual as of the date published and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of Capital Group or its affiliates. This information is intended to highlight issues and should not be considered advice, an endorsement or a recommendation.

Tom Hollenberg

Tom Hollenberg