Market Volatility

India

India’s incumbent Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) secured a third term on June 4, 2024, with the BJP-led National Democratic Alliance (NDA) clinching a win in the country’s closely watched national election.

In contrast to the 2014 and 2019 elections, the race was tighter than expected, with the BJP failing to secure a simple majority on its own in the lower house of parliament. This has created some uncertainty around the direction of policy over the next five years. India’s equity market fell sharply on the news but recouped losses in subsequent days.

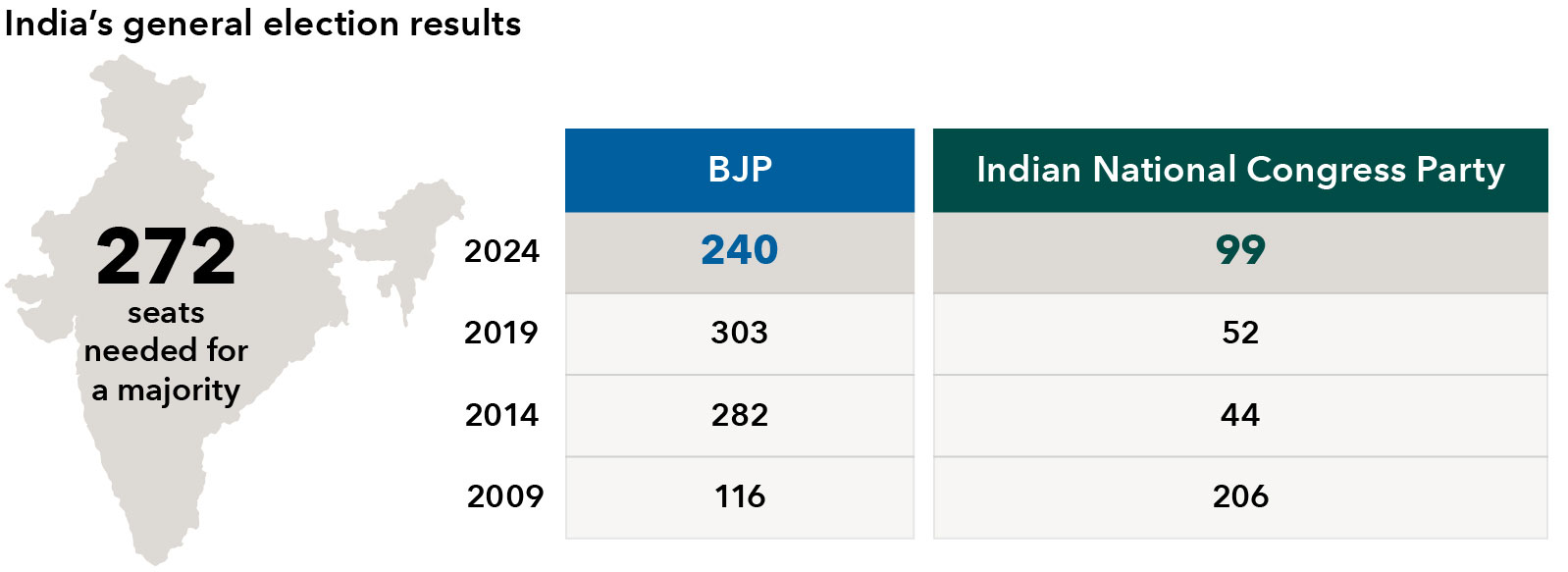

In the six-week election that began in April, the BJP won 240 seats in the country’s 543-member parliament, falling short of market expectations of 300 or more and the 272 seats needed to secure a majority on its own. The result was also less than the 282 seats the BJP secured in the 2014 election and 303 in 2019. The outcome means India will once again see a coalition government after 10 years, which had been the norm since 1989.

The results were a big disappointment for the BJP. It had gone into this election expecting to easily best its 2019 result. Nevertheless, it is still impressive that the alliance secured a comfortable majority after being in power for 10 years, as some voter fatigue was bound to have crept in. The BJP waged its election campaign in the name of Modi, and clearly at the margin, the Modi brand has diminished.

The key events to watch out for in the coming weeks and months are the formation of the cabinet, the selections to the key ministries and the budget scheduled to be presented in July. So far, it appears that key appointments will be retained by the BJP.

Modi was sworn in for his third term as prime minister on June 9, along with 72 ministers, 30 of which are cabinet ministers. As we look ahead, here are some potential implications and key questions to think about.

Will it be a stable coalition?

This is the most pressing question on everyone’s mind. Demands of coalition partners often make way for a seemingly unstable government that can stymie decision making.

There are two things to bear in mind: First, with BJP at 240 seats, this is the strongest coalition government since 1989. If the support of two major coalition partners — the Telugu Desam Party (TDP) from the southern state of Andhra Pradesh and Janata Dal (United) from Bihar — remains steadfast, then there is no reason for this government to be unstable. These long-standing NDA allies can ensure a steady coalition, provided their key demands are met.

TDP leader Nara Chandrababu Naidu is regarded as the original reformer and has been one of India’s most forward-looking chief ministers, who has pushed for economic transformation. The inclusion of these parties in the coalition will likely temper divisive rhetoric that has heightened social tensions.

India sees first coalition government in a decade

Sources: Capital Group, media reports. Data as of June 2024

The stability of the government will not be a function of just the alliance partners. BJP will have to rein in its members from making statements that could upset the alliance and potentially destabilize it. Moreover, senior leaders of the BJP and the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, the BJP’s ideological front, are likely to be more assertive this term than in the last 10 years.

The opposition alliance led by the Indian National Congress Party has been hinting that at the appropriate moment, it would like to form the next government. It means that it will try to woo away the NDA partners, placing the onus to prevent such a move on the BJP. The opposition parties would also make it difficult for the new government to pass any contentious legislation, and it could try to hobble its functioning.

Likely key demands of the major coalition partners

A long-standing demand of Andhra Pradesh and Bihar has been the granting of special status to the two states, which will give them additional funds from the central government. Even if the special status is not granted, the two states could demand special financial packages for their development. The alliance partners are also likely to demand key cabinet ministries if the past is any indication.

Depending on the allocation of these posts, Prime Minister Modi will not have the same control over the ministries. Going by the names of the ministers sworn in, there has been no change in the important posts of home, finance, defense and external affairs.

A coalition government could slow decision making

On the upside, the new government is likely to see more collective and consensus-oriented decisions with greater transparency. Depending on the ministries that the coalition partners control, the election results will likely impede Modi’s ability to appoint technocratic ministers, and the priorities of the ministries may change or get recalibrated. Hence, the profile of the new cabinet, as well as those key ministry posts non-BJP party members demand or receive, will give us a better sense of how the new government will function and its policy direction.

I would stress that a coalition government is not a doomsday scenario. It was India’s modus operandi from 1989 until 2014, when Modi was first elected as prime minister. Under various coalition governments, the economy, reform agendas and markets have done reasonably well. The medium-term economic growth trajectory is unlikely to change as there is almost no likelihood of repealing policy or reversing major government decisions.

Similarly, I do not expect any change in foreign policy. The new government will likely prioritize the national good and strengthen Western alliances rooted in mutual interests and democratic principles.

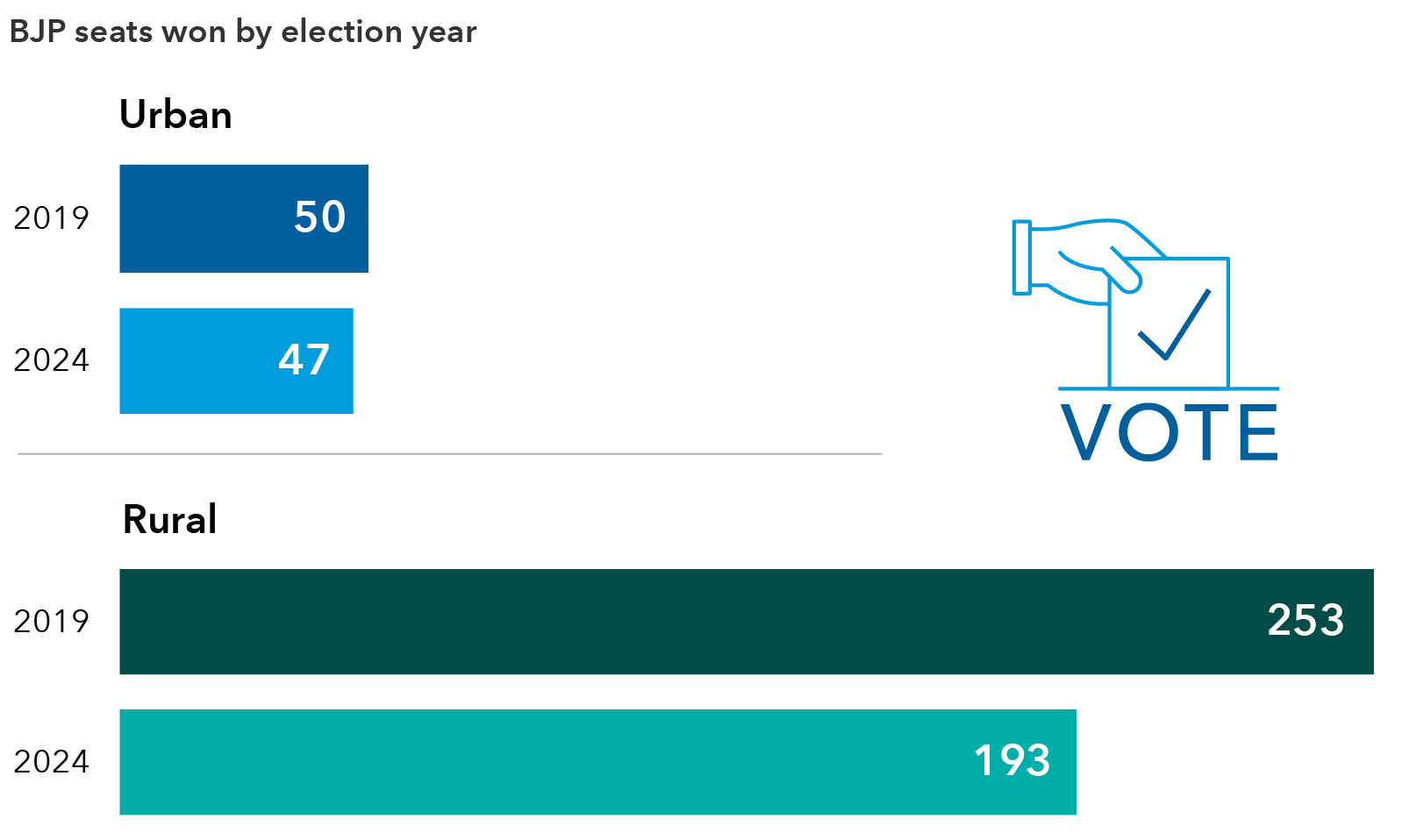

BJP loses edge with rural voters in 2024 election

Sources: Trivedi Center for Political Data, Election Commission of India, 2011 census, Mint calculations. A constituency is classified as urban if more than 50% of its population was urban during the 2011 census.

In the new parliament, the BJP will find it difficult to push through unpopular but necessary policy and reform measures. The privatization of banks will likely be one early casualty. Hopes of progress in land, agriculture and labor reforms will likely be ratcheted back as well. To be fair, there was not a high degree of hope that these reforms would progress given that the attempts over the last 10 years have not made much headway. As many of these have dual oversight by both federal and state authorities, there is the possibility of progress at the state level.

It would be easier to push reforms that do not require a change in legislation, since the opposition will have a significant voice in parliament, unlike Modi’s first two terms. The government will face more accountability and scrutiny both inside and outside the parliament. Hence, there will be more checks and balances on the functioning of the government and its various institutions.

Policy implications — business as usual with some recalibration

There should not be any major changes to the core economic focus of the last government — a push for higher investment in infrastructure, the growth of the manufacturing sector, an increase in its share of GDP and a focus on renewable energy and energy transition. Policies supporting domestic industries in strategic sectors like defense, space, semiconductors and energy are likely to continue, as well as the thrust into technology and digital public infrastructure.

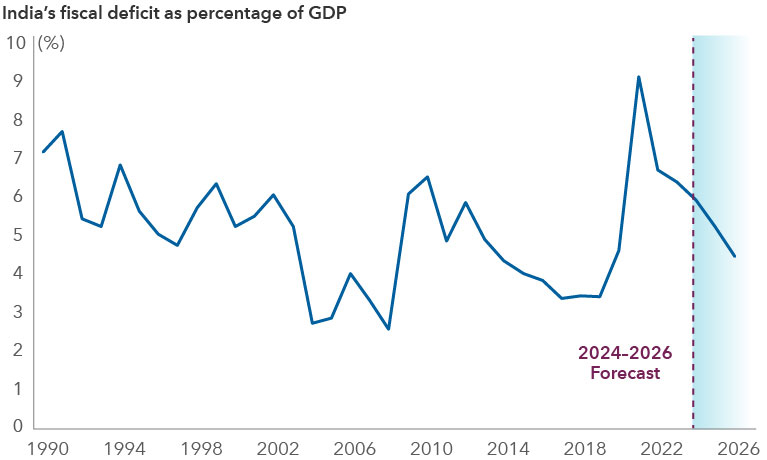

Meanwhile, we could see somewhat looser fiscal policies, which goes against the grain of BJP’s core ideology. Distress in India’s rural communities and joblessness were dominant themes in the opposition’s narrative. In the elections, BJP losses have been deeper in rural areas than in urban ones, relative to its performance in 2019. Further financial support for rural India and poor households could strain the government’s investment budget or increase the country’s fiscal deficit in the medium term.

However, both the BJP and TDP will likely seek macroeconomic stability and responsible economic governance. Thankfully, in the fiscal year 2025, there is headroom for higher spending given the government’s fiscal position. I expected that fiscal consolidation (policy intended to reduce deficits and the accumulation of debt) would proceed faster than what was targeted, but that may have to wait. That said, I don’t expect a deterioration of the fiscal deficit.

Sources: Capital Group, Indian government. Forecast data is shown from 2024 to 2026. Data as of June 2024.

The private sector is also likely to postpone investment decisions until there is greater clarity on government policies and their functioning. The new government will have to think more critically about employment and job creation. In his first speech after the election results, Modi reiterated that the new government would continue the policies of his outgoing regime.

There have been questions on the possible changes in tax policies. The BJP emphasized its policy of a stable and predictable tax regime in its manifesto. Thus, I do not expect any major changes. But there have long been rumors that a wealth or inheritance tax could be introduced in some form, and capital gains taxes could be rationalized across asset classes. We could see some move in this direction.

There is a strong case for streamlining the goods and services tax regime, and potentially lowering taxes, which will need support from the states. While I do not expect any immediate change, there is a greater chance of progress on this front in the next one to two years. Similarly, I do not expect any major changes to corporate taxes.

Will Modi be replaced as prime minister?

It’s possible, but it seems unlikely. There are two scenarios under which there can be a new prime minister: First, BJP’s allies demand a change and want someone who is more flexible; second, BJP partners walk out of the coalition to support the opposition led by the Congress Party. Both seem highly unlikely as of now.

The NDA has already chosen Modi as its prime minister, and he was sworn in on June 9. Moreover, Modi still remains India’s most popular politician and continues to have very high approval ratings. After 10 years in power, the BJP is the single largest party in parliament, and its share of seats is more than the number held by the opposition alliance. The BJP has also made reasonable inroads into states in eastern India and southern India where it has hitherto had a limited presence.

What were other surprises in this election?

The biggest surprise in this election was from Uttar Pradesh, a northern state that sends 80 members to parliament. I expected that the BJP would hold its ground or increase its seat share. However, BJP won only 33 seats, versus 62 in 2019 and 71 in 2014. Two other large states, where the results were worse than expected for BJP, are Maharashtra and West Bengal.

It has not been all bad news for BJP. In significant parts of the northern belt, the party remains dominant. For the first time, it has won the mandate to rule in the eastern state of Odisha and won its first seat to parliament from the southern state of Kerala. It has also increased its vote share in the southern states of Telangana and Tamil Nadu, where it had only a modest presence in the past.

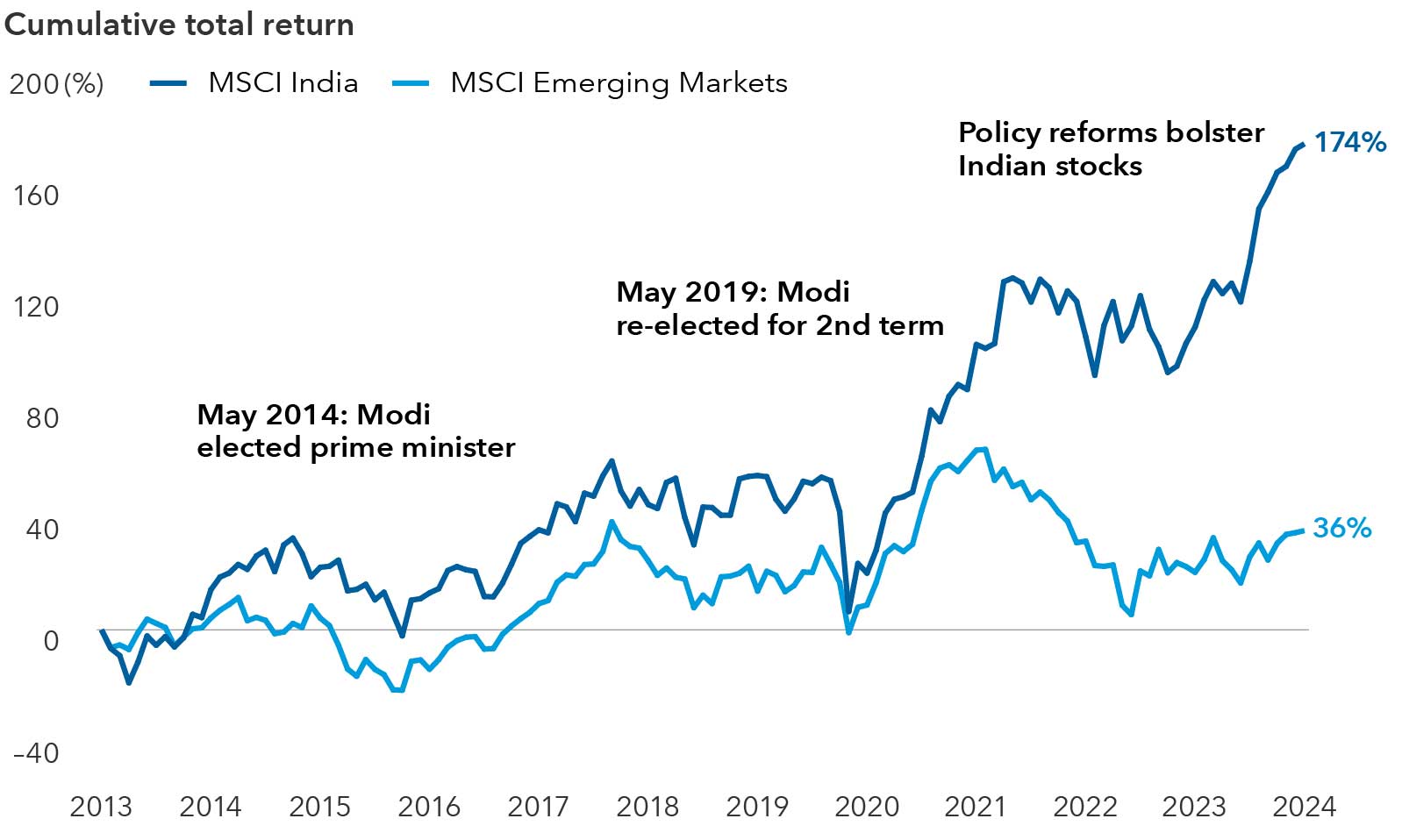

Equity markets are likely to be volatile after a strong run

Markets will likely be volatile until there is more clarity on the formation of the cabinet, the key ministers and the policy direction of the new government.

Indian stocks have surged during Modi’s tenure

Sources: MSCI, RIMES. Data as of May 31, 2024.

While the cabinet formation should be known in a couple of weeks, the July budget would be one of the first statements on economic direction. Until then, small- and mid-cap stocks could continue to face selling pressure, particularly in sectors dependent on continued policy momentum. If the past is any indicator, the market’s immediate reaction usually reverses once a new government has formed, and the trajectory of growth and reform become clearer. The MSCI India Index has posted one of the strongest returns in the world over the past 12 months, notching a gain of more than 35% through June 7. By comparison, the S&P 500 Index has risen 24%.

The MSCI India Index is designed to measure the performance of the large- and mid-cap segments of the Indian market.

MSCI has not approved, reviewed or produced this report, makes no express or implied warranties or representations and is not liable whatsoever for any data in the report. You may not redistribute the MSCI data or use it as a basis for other indices or investment products.

Our latest insights

-

-

Market Volatility

-

Market Volatility

-

-

Artificial Intelligence

Never miss an insight

The Capital Ideas newsletter delivers weekly insights straight to your inbox.

Anirudha Dutta

Anirudha Dutta