Market Volatility

Fed

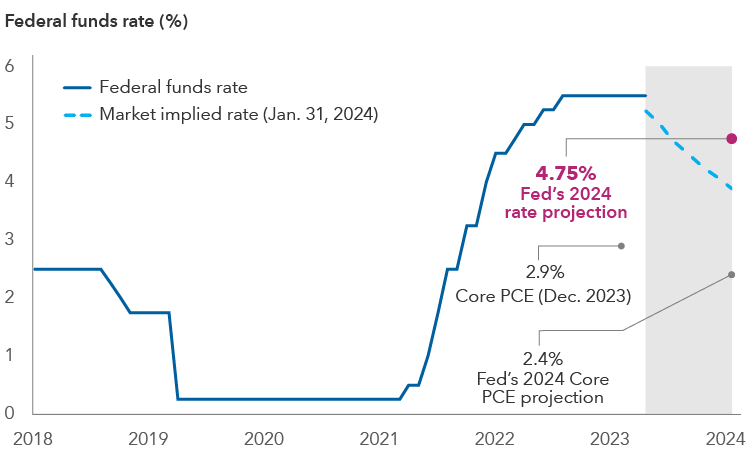

The Federal Reserve left its benchmark interest rate unchanged at a range of 5.25% to 5.50% for the fourth consecutive meeting, but did not tip its hand as to when cuts may begin.

The Fed’s official statement removed language about the potential need for further tightening but emphasized that the central bank’s governors still require “greater confidence that inflation is moving sustainably toward 2%” before moving to lower borrowing costs.

“Almost every participant on the [Federal Open Markets Committee] believes it will be appropriate to reduce rates,” said Fed Chair Jerome Powell, acknowledging the fact that near-term inflation numbers look good. “What we are trying to do is identify a place where we are really confident about inflation getting back down to 2% so we can then begin the process of dialing back the restrictive level.”

“Based on the meeting today, I would tell you that I don't think it is likely that the Committee will reach a level of confidence by the time of the March meeting to identify March as the time to [begin cutting], but that is to be seen,” Powell added.

Fed has room to cut rates, even in a growing economy

Sources: Bloomberg, Federal Reserve, Bureau of Economic Analysis. Data as of January 31, 2024.

Market pricing after the January 31 meeting showed investors appear to believe the Fed will cut rates by around 140 basis points (bps) by the end of the year. This is higher than the Fed’s most recent dot-plot projections of 75 bps and reflects a view that the central bank is likely to deploy “maintenance cuts” as inflation continues to slow, even if growth stays positive.

Market valuations are reflecting a Goldilocks economic scenario of slowing inflation and resilient growth, supported by easier monetary policy. While a recession is not the base case, there are signs that markets could be overly optimistic about the economy. The risk is that markets are underestimating the potential impact of one of the sharpest tightening cycles in decades. Even if one has a baseline expectation for a soft landing, the margin of error reflected in current bond pricing seems very thin.

Valuations across fixed income sectors suggest it may be prudent to consider adding some defensive positioning. Since the Fed’s pivot at its December meeting, there have been strong excess returns across various bond sectors. Investment-grade (BBB/Baa and above) credit spreads are nearing their tightest levels since before the global financial crisis. A bias for higher quality securities may be appropriate as the current pricing of lower rated credits does not appear to reflect the potential downside risk.

The core Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) Index (the Fed’s preferred gauge of inflation) dipped below 3% year over year in 2023 and is now below 2% on three-month and six-month bases. As a result, the central bank is likely to begin rate cuts even as the economy continues to expand. Maintenance cuts may be greater than the Fed's projection (e.g., if inflation falls below 2.5% by the end of 2024 and the Fed wants to bring the real monetary policy rate down to 1%, this would imply the federal funds target rate should fall to 3.5%, entailing 200 bps of cuts by the end of 2024).

According to both Governor Christopher Waller and Chair Powell, the Fed will be closely watching the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ revised Consumer Price Index (CPI) data released on February 9. The Fed will be looking for confirmation that the near-term inflation trend is sustainable, particularly as revisions to CPI this time last year surprised to the upside.

Should a recession materialize, additional cuts would likely be implemented. Given the recent decline in interest rates, positioning for a steeper yield curve may offer more attractive risk-reward than an overweight to duration.

Labor market strength remains a key variable to achieving a soft landing. So far, the labor market appears to be reaching balance without significant loss of jobs — but there are areas to watch such as aggregate employment measures and revisions to nonfarm payrolls, which have been negative in 11 out of the last 12 months. Additionally, the larger-than-expected fiscal stimulus and liquidity from the decline in usage of the Fed’s Reverse Repurchase (RRP) facility were both supportive of strong economic growth in 2023. Both factors are expected to be weaker this year.

The value of fixed income securities may be affected by changing interest rates and changes in credit ratings of the securities.

Bond ratings, which typically range from AAA/Aaa (highest) to D (lowest), are assigned by credit rating agencies such as Standard & Poor's, Moody's and/or Fitch, as an indication of an issuer's creditworthiness. If agency ratings differ, the security will be considered to have received the highest of those ratings, consistent with the fund's investment policies.

The Consumer Price Index (CPI) is a measure of the average change over time in the prices paid by urban consumers for a market basket of consumer goods and services.

Credit spread — A credit spread is the difference in yield (the expected return on an investment over a particular period of time) between a government bond and another debt security of the same maturity but with different credit quality.

Duration measures a bond’s sensitivity to changes in interest rates. Generally speaking, a bond's price will go up 1% for every year of duration if interest rates fall by 1% or down 1% for every year of duration if interest rates rise by 1%.

Inflation — The rise in the prices of goods and services, as happens when spending increases relative to the supply of goods on the market — in other words, too much money chasing too few goods. Core inflation metrics strip out volatile items like food and energy.

Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) — A measure of the prices that people living in the United States, or those buying on their behalf, pay for goods and services. The PCE price index is known for capturing inflation (or deflation) across a wide range of consumer expenses and reflecting changes in consumer behavior. Core PCE excludes food and energy.

Yield curve — A measure of the difference between the yields of bonds of different maturities. A yield curve is said to be inverted when shorter term bonds provide higher yields than longer term bonds.

Our latest insights

-

-

Market Volatility

-

-

Artificial Intelligence

-

Interest Rates

Never miss an insight

The Capital Ideas newsletter delivers weekly insights straight to your inbox.

Margaret Steinbach

Margaret Steinbach