Market Volatility

Inflation

Against the specter of soaring energy prices, labor shortages and supply chain constraints, a question that has arisen in the U.S. has landed firmly on European shores: Will inflation continue to rise and how persistent will it be?

The prevailing school of thought is that inflationary pressures will diminish once economies are past the post-COVID recovery, and Europe will return to its decade-old pattern of low growth, low inflation and low interest rates. My view is that the pandemic has brought about changes in consumer behavior and the political climate that, when combined with secular shifts that were already underway, will likely result in a shift to higher inflation in the range of 2% to 3% in Europe over the next few years. I expect eurozone real gross domestic product to increase to around 5% in 2021 and 4.5% in 2022, with the U.K. economy growing by around 7% in 2021 and 5% in 2022.

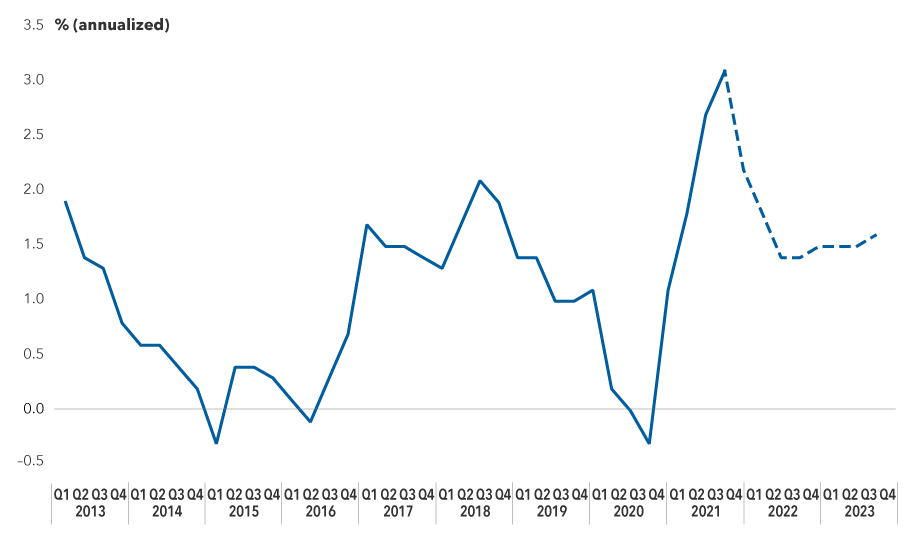

Eurozone inflation has recently climbed above its medium-term target of 2%

Source: European Central Bank. Annualized quarterly data as of October 15, 2021.

Interest rates could shift moderately higher, but that will depend largely on the reaction of the European Central Bank (ECB) and the Bank of England (BOE). The ECB has held its main refinancing operations rate at zero since March 2016 and does not seem likely to raise rates in the foreseeable future. It did, however, begin slowing the pace at which it is buying bonds through its Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) in September. It is likely to let the program expire in March 2022.

The BOE cut its benchmark bank rate to 0.1% in March 2020. Markets are pricing in an expected rate hike of approximately 0.25% by the end of the year, with more hikes in 2022.

Here are six reasons why I expect to see higher inflation and faster growth in Europe over the next few years:

Central bank benchmark rates and market expectations

Source: Bloomberg. Data as of October 15, 2021. The futures implied rate reflects market expectations for rate changes for December 2021.

1. Structural shifts in energy will keep prices higher

Industry is booming in Germany and the U.K., so there has been a rise in demand for energy. At the same time, both cyclical and structural factors have lowered supply.

For natural gas, Europe is dependent on Russia and Norway, where there have been significant outages. That is partly due to politics and partly due to infrastructure, in terms of just not being able to get the gas into the rest of Europe. The shortages are also related to the fact that last winter was actually quite cold and thus Europe didn't build up any gas reserves.

Capital Ideas™ webinars

Insights for long-term success

This combination of very strong demand and low reserves has been made worse by the slow pace of transition to renewable energy. Europe is still too reliant on fossil fuels. Wind and hydroelectric plants, for all kinds of reasons, haven't been producing enough electricity to meet base requirements. Europe needs to build out much more renewable energy capacity, which is going to take some time. And that means this supply problem is likely to be present for years to come.

I think the prices that we're seeing today are probably an overshoot. But even if they are an overshoot, the fact is that the demand and supply fundamentals will tell you that energy prices six months ago were just far too low. Given that energy has a weight of 9% in the eurozone consumer price index, these price increases will push up headline inflation rates over the next few months.

2. Consumers appear to keep their wallets open

Household savings have increased sharply as consumers have been housebound for a large part of the last 18 months. Now those savings are being released.

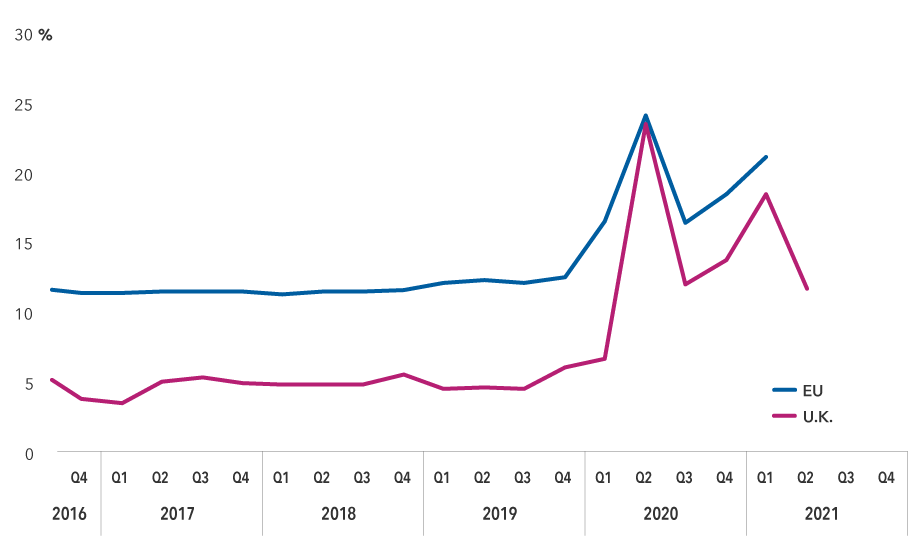

The EU household saving rate had tracked somewhere around 12% since 2008, before doubling in early 2020 as lockdowns swept the continent and the ECB unleashed the first wave of its €1.85 billion stimulus program.

Europe’s household gross saving rate surged during the pandemic

Sources: Eurostat, U.K. Office for National Statistics. Data as of October 18, 2021.

Before the pandemic, household consumption was heavily weighted toward services and away from durable goods, particularly in Europe and the U.S. People bought cars, refrigerators and bikes, but they spent most of their money on services like going out to restaurants and traveling. That flipped during the pandemic.

Economists are now wrestling with the question: Is this change in consumption a temporary thing and will we go back to normal pre-pandemic patterns? I think the honest answer is, we don't know.

If the demand for durables remains robust, it's arguable that there isn't enough capacity to produce what we need. And that's a long-term structural issue.

3. Labor shortages are likely to persist

There is also mounting evidence of acute labor shortages in some economies, which raises the probability that higher headline inflation rates could feed through to higher wage growth. German unions, for example, are sounding more determined in the run-up to the next round of pay negotiations in the spring. We have already seen a significant pickup in wage growth in the U.K. as the economy has reopened.

There was a significant exodus of labor away from the service sectors during the pandemic. The shift has been pronounced in economies like the U.K., Italy and Spain. A section of the labor force migrated from services to assembly jobs in manufacturing. And manufacturing has seen a huge upswing because demand has been so strong. So, there are labor shortages across industries.

While the labor mismatch in the eurozone isn’t as pronounced as in the U.K., and wages are still growing only modestly, ECB policymakers are worried that labor shortages and effective wage indexation could lead to a sharp rise in wage growth in 2022.

4. Supply constraints are showing up across many industries

It's tempting to say the supply issues will go away. The fact is that we just don't know how long it will take to resolve them, and indeed, there is a much more fundamental structural problem in many markets.

Our equity analysts inform us some Asian countries are experiencing huge spikes in COVID cases and are mandatorily shutting down manufacturing facilities as a result. And there are also massive delays to load and unload cargo ships. The backlog of ships has grown so severe at the port of Felixstowe, which handles around 36% of the U.K.’s freight container volume, that Swedish shipping company Maersk has said it is diverting a third of its ships bound for the port elsewhere.

Bottlenecks started in the U.S. and China, where a COVID outbreak at one of its busiest ports resulted in a multiweek shutdown. Now the dysfunction is spreading to many other global ports that are providing overflow relief. This is resulting in multiweek delays in product deliveries for finished goods, and many manufacturers can’t even get the necessary parts to make their products in the first place.

5. Back to Keynes — Fiscal policies will remain stimulative

I believe we are close to a change in the policy regime that is a complete reversal of what we saw in the early 1980s with Thatcher and Reagan. I think we're now in a much more pragmatic world similar to the 1960s, where governments were more willing to use fiscal policy to do public investment.

The orthodoxy of the last 20 to 30 years has been that monetary policy is the primary instrument for managing demand, with fiscal policy playing a subordinate role. But if Germany, for instance, is spending €80 billion on public investment, that's 2% of its gross domestic product. If you get the same in France, Italy and maybe even the U.K., then that raises the growth potential of these economies in the medium to longer run.

In the West, we've seen a long-term downtrend in investment as a share of the economy. Partly that's about private investment, but there's also been significant underinvestment in public infrastructure.

Governments know they made mistakes after the global financial crisis when they tightened fiscal policy too quickly. I think they will be at pains not to repeat those errors.

6. Central banks don’t want to raise rates at the wrong time

Central banks’ response to the COVID crisis had been to pin the pedal flat to the floor and print money at a rate not seen before. Now, with Europe facing inflationary pressures that are also visible in other parts of the developed world, it appears the ECB is thinking about easing off the accelerator and the BOE is ready to step on the brakes.

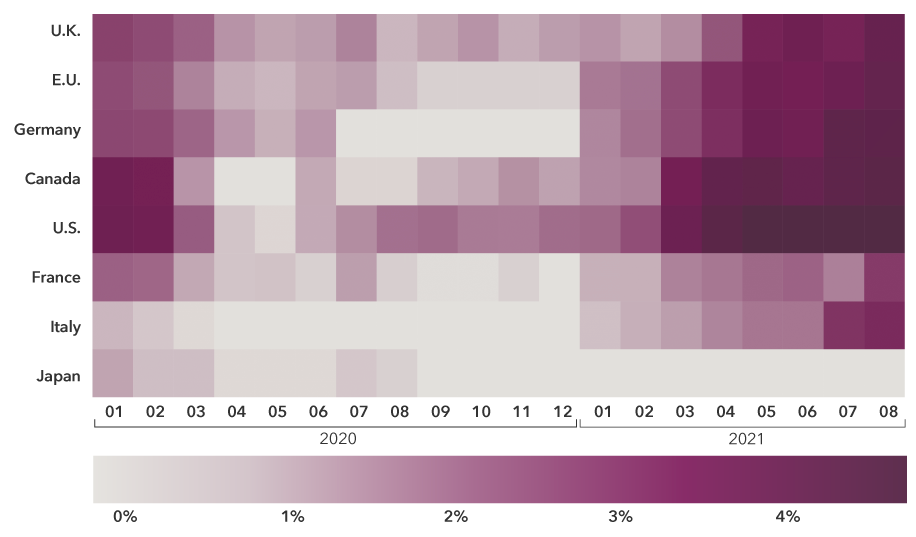

Inflation surges across most of the G7

Source: OECD, as of October 15, 2021. Darker colors indicate higher inflation.

The BOE’s monetary policy committee signaled a hawkish turn in September with the publication of its policy meeting minutes. While they voted to maintain its current policy stance, there were some clear signals of an emerging tightening bias.

Christine Lagarde, president of the ECB, has indicated publicly that it is not planning to tighten. But the minutes of the ECB’s latest meeting also show some governing council members are growing concerned about upside risks to its inflation forecast.

It seems likely to me that both central banks will tighten before markets expect, and the BOE is likely to react more swiftly than the ECB. By moving early, central bankers hope they can avoid bigger inflation problems and more aggressive tightening later, which would be more of a threat to the recovery.

Central banks must determine to what extent higher prices will choke off demand and growth. I think that is where most central bankers are really scratching around for an answer. The challenge is that the traditional models of relationships between labor, inflation and prices have broken down.

The ECB appears to be particularly concerned with not repeating the mistakes of 2011, when it stymied growth by raising rates at the wrong time. The bigger risk, in my view, is that the bank could make exactly the opposite mistake. If the ECB leaves its policy too loose for too long there's a danger that, at some point, we could end up with an inflation problem that's much bigger than we have today.

Investing outside the United States involves risks, such as currency fluctuations, periods of illiquidity and price volatility. These risks may be heightened in connection with investments in developing countries.

BLOOMBERG® is a trademark and service mark of Bloomberg Finance L.P. and its affiliates (collectively “Bloomberg”). Bloomberg or Bloomberg's licensors own all proprietary rights in the Bloomberg Indices. Neither Bloomberg nor Bloomberg's licensors approves or endorses this material, or guarantees the accuracy or completeness of any information herein, or makes any warranty, express or implied, as to the results to be obtained therefrom and, to the maximum extent allowed by law, neither shall have any liability or responsibility for injury or damages arising in connection therewith.

Our latest insights

-

-

Market Volatility

-

Market Volatility

-

-

Artificial Intelligence

Never miss an insight

The Capital Ideas newsletter delivers weekly insights straight to your inbox.

Robert Lind

Robert Lind