Market Volatility

U.S. Equities

If you’re not keeping an eye on the debt binge in corporate America, it’s time to pay attention, according to three Capital Group investment team veterans. Non-financial corporate borrowing has soared to a record high of $9.95 trillion, or 47% of GDP, as of June 30, 2019, according to the Federal Reserve.

What’s driving this debt deluge? Years of low interest rates, combined with two Federal Reserve rate cuts in 2019, have likely extended the more than 10-year-old U.S. economic expansion, and market returns have been reasonably strong.

Unconventional monetary policy decisions — aided by persistently low inflation — are giving heavily leveraged U.S. companies incentives to continue borrowing.

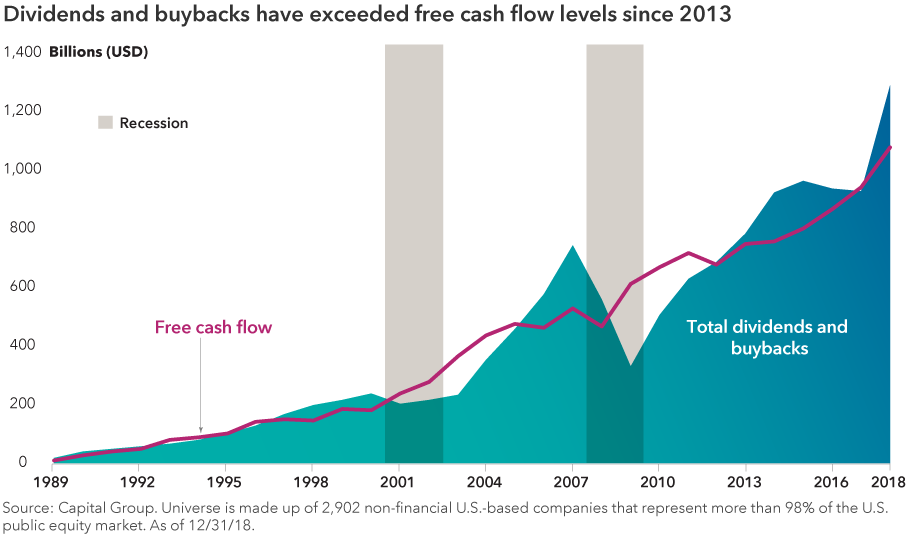

Much of the debt has been used to fund dividends, share buybacks and acquisitions. In many cases, these actions are helping to inflate reported earnings and share values.

So, what does this mean for companies, investors and the economy? Could this binge on cheap debt be the road to the next recession? Capital Group’s investment team is closely watching three key signals.

1. Not all dividend payments are sustainable

Joyce Gordon, portfolio manager, American Mutual Fund® and Capital Income Builder®

One important lesson I learned during the global financial crisis in 2008 and 2009 is to avoid companies with a lot of debt this late in the cycle. Companies with significant debt service face a number of challenges. For example, some companies today are issuing debt to buy back shares and pay their dividends, rather than using free cash flow.

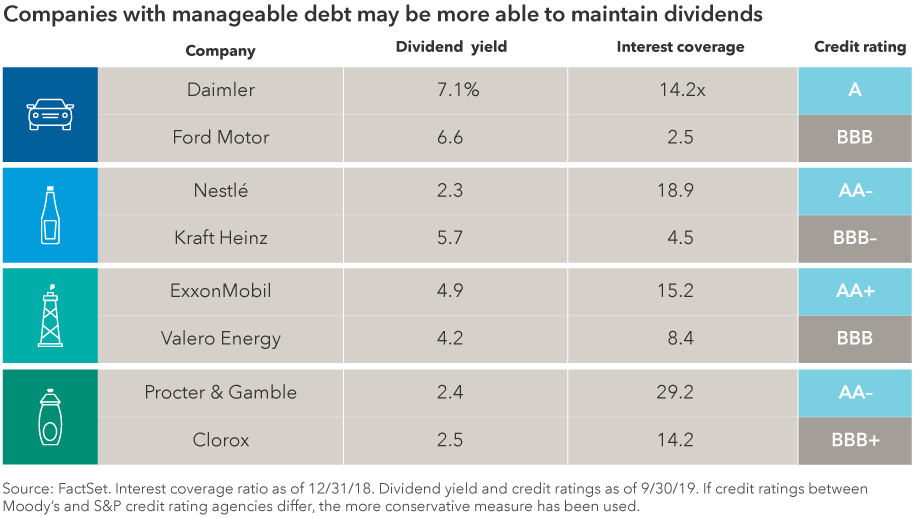

It’s tempting for companies to do this because rates are so low, but it can be a warning sign. If rates rise and a company has trouble funding its debt, it may have to consider cutting its dividend or reducing share buybacks. I look carefully at companies with BBB credit ratings on the lower end of the investment-grade spectrum. If conditions deteriorate, some of these companies may be among the first to cut their dividends to preserve their ratings.

I have also seen some companies that have typically increased their dividend every year that have yet to do so over the past year. And in many cases, these have been the companies with a lot of leverage that are concerned about paying down debt. We have seen this with some of the food companies. It suggests that sales growth is tougher in this late-cycle environment.

At this point, I’m very focused on higher quality companies with very strong balance sheets that are less likely to have funding problems and are able to maintain dividend payments if we go into a recession.

2. Sooner or later, excesses will be recognized

Dane Mott, global accounting analyst

At this point in the cycle, companies appear to have become more comfortable with taking on debt.

Debt has been an engine for dividends and share buybacks as well as the significant amount of acquisitions that have been a hallmark of this long cycle. A look at data for U.S. companies in aggregate, shows that since 2013, dividends and stock buybacks have generally exceeded free cash flow generation. Companies have filled that funding gap through debt issuance, thanks to low interest rates and easy access to debt.

Companies cannot spend more than they make indefinitely. A look at interest coverage ratios ― which measure a company’s ability to service debt ― paints a picture that is reminiscent of 1998–1999, a period of elevated leverage shortly before a recession. History, of course, does not necessarily predict the future, but experience navigating similar periods can be informative.

What’s more, many companies that have been active in making acquisitions have reported solid earnings growth, but such cases require nuanced analysis because acquisitions can distort perceptions of company growth and health, and those distortions can be reflected in market prices. Acquisitions can be flattering to a company’s earnings because many of the costs associated with them can be excluded from some measures of earnings and hidden on balance sheets.

To be sure, in many cases companies have been borrowing prudently and investing capital efficiently. But it is important to be aware of the companies that have taken on excessive leverage and be mindful of the risks associated with this behavior. Being able to distinguish between those groups of companies will serve investors well when we enter tougher parts of the cycle.

3. Is the BBB bond market a systemic risk?

David Lee, portfolio manager, American Funds Corporate Bond Fund® and The Bond Fund of America®

This late in the cycle, I think it’s prudent to take a cautious approach to corporate debt. The market appears to be on high alert, ready to pull back on any hint of negative news. The upcoming U.S. presidential election is amplifying uncertainty around the trade war with China, Brexit, and Fed policy.

The good news is that companies have borrowed at very low interest rates and, on the whole, they have been somewhat disciplined about the debt they’ve taken on. What’s more, corporate profits have increased significantly in the past decade. Profitable companies generally have ample free cash flow and can easily make interest payments when they’re due. The low interest rate environment and drive to increase shareholder value have contributed to more companies willing to operate with higher debt loads.

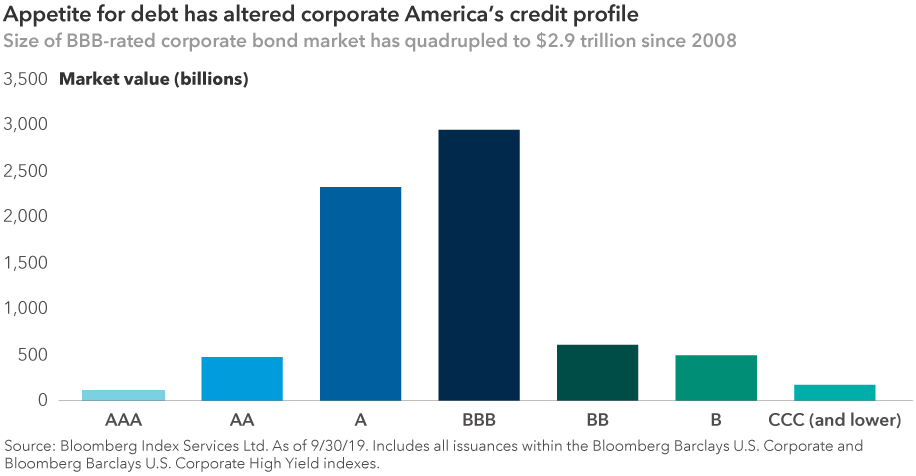

Against this backdrop, the rise of triple-B corporate debt — the lowest investment-grade rating — is a development I’m keeping an eye on. There is now around $2.9 trillion of U.S. BBB corporate debt outstanding, which is more than four times as much as in 2008. These bonds account for 50% of investment-grade corporate debt.

Despite this profound change in corporate America’s credit profile, we have seen many firms where higher quality companies are keenly focused on protecting their investment-grade credit ratings. There is a willingness to take measures such as cutting dividends to retain the access to relatively cheap capital that comes with an investment-grade rating.

Although an imminent recession seems unlikely, the rise in BBB-rated corporates suggests that the next downturn may see a record number of downgrades to high yield due in part to the larger size of the market today. That would likely cause BBB and BB credit spreads to widen dramatically.

A wave of downgrades may also make it more difficult for investors to buy and sell bonds, because available dealer liquidity has not kept pace with the growth in the market. This could also contribute to corporate credit spreads widening.

Of course, credit spreads (the yield gap between corporates and Treasuries) may also widen even if downgrades don’t pick up. Significantly weaker economic data, geopolitical shocks or other escalating signs of recession could also be triggers. Because investment-grade companies tend to be under-researched on the credit side, volatility has a silver lining: creating attractive entry points for selective investors such as Capital.

Bond ratings, which typically range from AAA/Aaa (highest) to D (lowest), are assigned by credit rating agencies such as Standard & Poor's, Moody's and/or Fitch, as an indication of an issuer's creditworthiness. If agency ratings differ, the security will be considered to have received the highest of those ratings, consistent with the fund's investment policies. Securities in the unrated category have not been rated by a rating agency; however, the investment adviser performs its own credit analysis and assigns comparable ratings that are used for compliance with fund investment policies.

Our latest insights

-

-

Market Volatility

-

-

Artificial Intelligence

-

Interest Rates

Never miss an insight

The Capital Ideas newsletter delivers weekly insights straight to your inbox.

Statements attributed to an individual represent the opinions of that individual as of the date published and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of Capital Group or its affiliates. This information is intended to highlight issues and should not be considered advice, an endorsement or a recommendation.

Joyce Gordon

Joyce Gordon

David Lee

David Lee

Dane Mott

Dane Mott