Market Volatility

Europe

The incoming Trump administration is already signaling aggressive action on trade, with likely tariffs on U.S. imports. Alongside China, President-elect Donald Trump has identified Germany as a problem. This is not surprising, as the U.S. is running a sizeable bilateral current account deficit with Germany, principally reflecting a large deficit in goods.

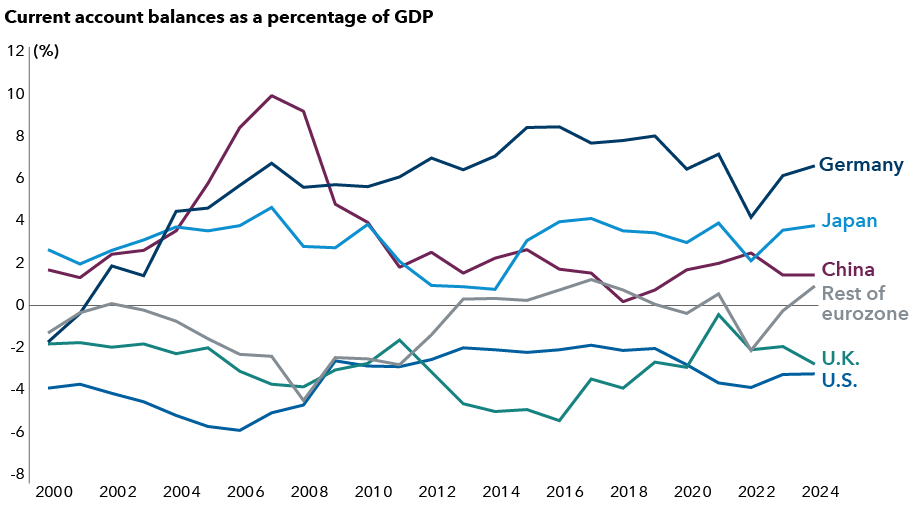

Germany’s overall current account surplus is back to around 6% of its GDP, much larger than Japan’s, China’s or the rest of the eurozone combined. In effect, the U.S. and U.K. have been running structural current account deficits over recent decades, offset by structural surpluses in Germany, Japan and China.

Germany’s current account balance outweighs global peers

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook. Data as of November 13, 2024.

Trump says he believes these countries are taking advantage of the U.S. In Germany’s case, he is equally concerned about Berlin’s reluctance to increase its defense spending in line with NATO’s 2% GDP target. Perhaps understandably, there is growing anxiety in Germany about the potential impact of a trade war with the U.S. In some sense, Trump's approach may represent a return of the geopolitical strategy of mercantilism.

Trump is not the first U.S. president to express concern about Germany’s large trade surplus. In the 1970s, Richard Nixon introduced a policy known as the “Nixon Shock,” which closed the gold window and triggered the end of Bretton Woods, when Germany became reluctant to accumulate dollar assets or reduce its trade surplus. In the 1980s, Ronald Reagan and Treasury Secretary James Baker strong-armed Germany to sign up for the Plaza Accord to weaken the dollar and boost the Deutsche Mark as a way of closing the U.S. trade deficit and Germany’s trade surplus.

These analogies show the U.S.-German trade relationship is more nuanced than Trump’s rhetoric implies. Germany has run large surpluses for many years, to the consternation of its European trading partners as much as successive U.S. administrations. But the counterpart of its current account surplus is that Germany has been running a capital account deficit as it recycles its excess saving to the U.S. and European neighbors.

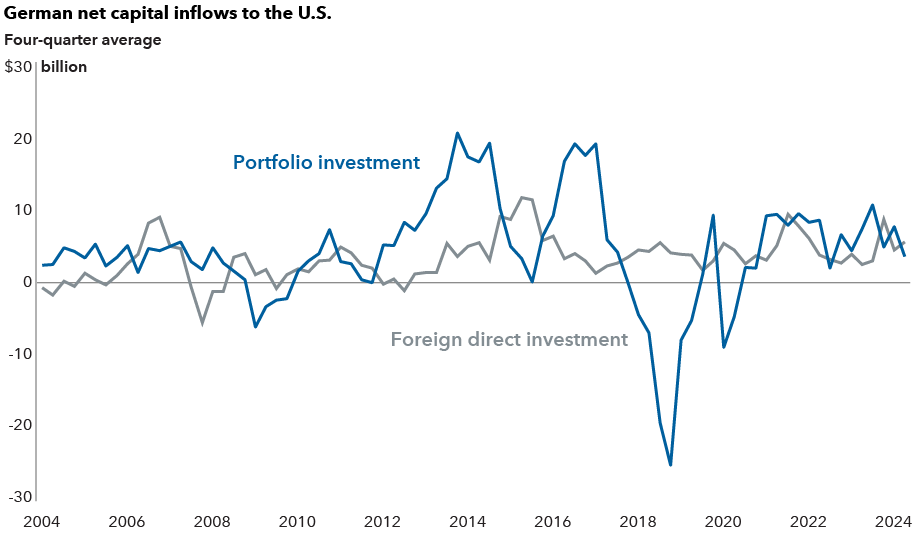

The U.S. has been recording significant net capital inflows (both foreign direct investment and portfolio investment) from Germany as a result. Importantly, as the chart below highlights, when the first Trump administration started to crank up its trade rhetoric and tariffs, Germany’s net portfolio inflows to the U.S. dropped sharply.

While the incoming administration might be focused on the goods trade position, it is important to take a more holistic view of flows in both trade and capital. A mercantilist view of the U.S.-German trade imbalance suggests Germany is “winning” and the U.S. “losing.” However, a view grounded in open-economy macroeconomics suggests the trade deficit between the U.S. and Germany is the counterpart of capital flows between the two, as well as a reflection of differences in national saving and investment rates.

German foreign direct investment remains steady

Chart source: Bureau of Economic Analysis. Data as of November 13, 2024.

When a country’s saving rate is higher than its investment rate, it runs a current account surplus and can export this surplus to other countries. When the savings rate is below the investment rate, a country runs a current account deficit and may import savings (capital) from other countries. The U.S. and the U.K. have relatively low saving rates, which helps explain their current account deficits. China, Japan and European economies have higher saving rates, underpinning their surpluses.

We might argue Germany is sacrificing domestic consumption (effectively underconsuming) and running a higher saving rate, which it can then export to the U.S. This import of capital supports the U.S. dollar and enables the U.S. to overconsume — and so run a lower national saving rate. While U.S. consumers benefit from the willingness of Germany (and others) to consume less, U.S. policymakers have long argued this underconsumption is a deliberate policy to gain market share at the expense of U.S. producers. But it could also be the inevitable counterpart of the large U.S. current account deficit and tendency to overconsume, which boosts U.S. real interest rates and the dollar, and potentially crowds out demand in Germany, China and Japan.

What to expect in 2025 and beyond

The Trump administration’s trade objective appears to be to force these countries to consume more and run down their saving rates, likely through some combination of fiscal stimulus and higher private demand. But if his plan succeeds, it could reduce Germany’s saving rate and its capacity to recycle its excess to the U.S., which could mean a reduction in net capital inflows to the U.S., a weaker dollar, and higher inflation and interest rates.

In an open economy macro framework, these conditions would signal to the U.S. to reduce its domestic consumption and increase its saving rate. If the U.S. does not reduce demand as other countries boost theirs, the world could end up with significantly higher inflation and interest rates.

It is not yet clear how Trump’s administration would encourage current account rebalancing with Germany (and others). He seems unwilling to tighten U.S. fiscal policy, favoring an extension of tax cuts designed to support consumption. All else being equal, this would worsen the U.S. trade deficit. The incoming administration might hope threats of aggressive tariff hikes or loss of the U.S. security umbrella would be enough. Some rebalancing could happen even in the absence of action by Trump. Household saving rates in Germany should fall as confidence improves and the new government loosens fiscal policy to support growth. But this is unlikely to be on a scale that would satisfy the Trump administration, so the U.S. might seek an outright reduction in imports from Germany.

Since those attempts to manage trade imbalances in the 1970s and 1980s, which resulted in significant financial turbulence, we have seen a different regime over the last three decades. Differences in relative demand growth rates between economies have shown up in growing trade deficits/surpluses rather than in relative inflation/interest rates and exchange rates.

Policymakers have been willing to let capital flows offset trade imbalances, but if the Trump administration tries to manage trade and capital flows to reduce the deficit, it implies relative differences in demand could once again lead to greater instability in inflation, interest rates and exchange rates. That would represent a profound regime change for financial markets.

Bretton Woods — A system of monetary management that established the rules for commercial relations among 44 countries after the 1944 Bretton Woods Agreement.

Current account — Reflects the combined balances of trade in goods and services and income flows between one nation's residents and those of another country. A deficit occurs when the value of imports of goods, services and transfers exceeds total exports.

Mercantilism — An economic policy that aims to increase a country's wealth and power by limiting imports and promoting exports.

Nixon Shock — An initiative by President Richard Nixon in 1971, formally titled the New Economic Policy, changed both domestic and international economic policy, including wage and price freezes and import surcharges. The initiative included the suspension of the convertibility of the U.S. dollar to gold.

Foreign direct investment — When an investor in one economy becomes a significant or lasting investor in a business or corporation in a foreign country.

Portfolio investment — Cross-border transactions and positions involving equity or fixed income securities.

Don't miss our latest insights.

Our latest insights

-

-

Market Volatility

-

World Markets Review

-

-

Chart in Focus

Don’t miss out

Get the Capital Ideas newsletter in your inbox every other week

Robert Lind

Robert Lind

Beth Beckett

Beth Beckett