Bonds

The path of the COVID-19 pandemic and the global macro environment are likely to be key drivers of returns for emerging markets (EM) debt in 2021, as they were in 2020. Continued monetary and fiscal stimulus, a recovery in developed economies and less aggressive geopolitics have the potential to create a virtuous cycle for EM debt. On the other hand, rising national debts funded in international capital markets pose risks, as do looming elections in some EM countries. The specifics of each developing economy and local politics are likely to influence returns, leading to meaningful divergence within the asset class.

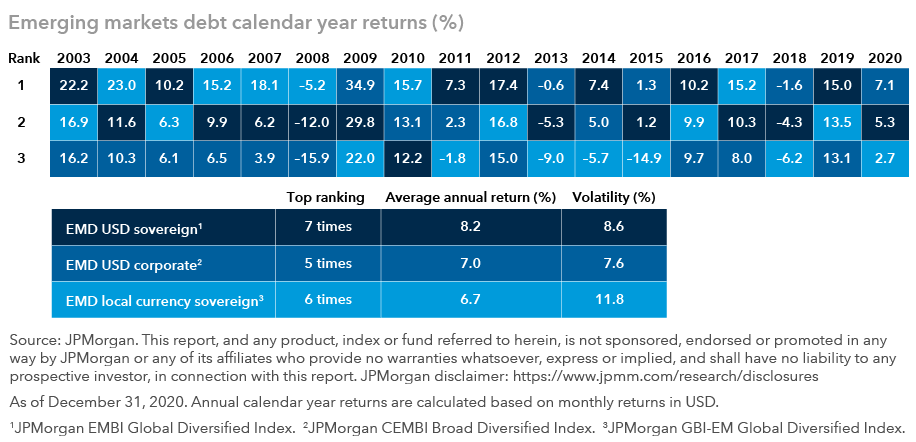

We see pockets of value in both U.S. dollar and local currency debt. While sovereign bonds continue to provide the bulk of the investment opportunity, we also find value in select corporate bonds. While recognizing that investors may have specific preferences for local currency or dollar-denominated debt within an asset allocation program, we see the greatest value in an actively managed, blended EM debt strategy.

After EM debt returned 5.8% in 2020, as represented by the JPMorgan EMBI Global Index, what does 2021 hold? In this article, we discuss the positive factors supporting EM debt as well as some of the challenges and where we see potential value in these markets.

The positives

Monetary policy: The liquidity created by the ultra-accommodative policies of major central banks provides a favorable backdrop for EM debt. The Federal Reserve’s new policy framework suggests a tolerance for inflation to overshoot its 2% target, signaling that its monetary policy is likely to remain easy for years to come. EM debt is one of the few fixed income assets that still offers decent yields in the 4% to 6% range, and it has been under-owned by institutional investors in recent years. This could support flows in the coming year, both for hard currency and local currency EM bonds.

Fiscal stimulus: Developed market economies entered 2020 with high sovereign debt. Over the past decade, many countries attempted to address their debt loads through austerity, but that approach is viewed to have failed and there is little political will or public appetite to continue down that path. With a focus now on massive fiscal stimulus — at least until the pandemic is behind us — EM countries stand to benefit by providing the commodities needed for large, state-sponsored infrastructure projects.

The commodities cycle: Commodities remain quite cheap and we have started to see an upturn in prices. Global oil demand is showing signs of recovery after a record drop in the first half of 2020, but it may take some time to return to 2019 levels. While we expect prices of commodities such as iron ore and copper to rise, we don’t believe that this commodities cycle will be as strong as the one following the 2008 financial crisis. That cycle was fueled by a huge construction boom in China that is unlikely to be repeated at such a large scale this time around.

EM bonds are one of the few markets to still offer decent yields

Growth in developed economies: The strength of the recovery in developed economies will be an important factor in the EM debt rebound — especially for developing countries that are significant commodity exporters, play a major role in manufacturing supply chains or rely heavily on tourism. There is hope for a global recovery in the second half of 2021 owing to monetary and fiscal stimulus, as well as broader distribution of COVID-19 vaccinations. However, a new coronavirus strain that could lead to extended lockdowns in some major economies poses some risk to this view. That said, we expect to see a return to some semblance of normal economic activity in the second half of the year.

Upturn in manufacturing cycle: As the global economy recovers, we expect an upswing in the manufacturing cycle to benefit EM economies. Despite political rhetoric, we doubt that a large-scale relocation of supply chains out of developing economies will occur, and recent data on manufacturing supports this view. The logistics of moving major factories and operations out of emerging markets are daunting. While some high-end manufacturing may move to developed economies, any diversification of low-end manufacturing away from China will likely be directed to other emerging markets.

The political backdrop: U.S. trade policies are likely to be less confrontational under a Biden presidency. Continued disagreements over trade policy, intellectual rights and technology are likely to persist, but a less confrontational and predictable approach should reduce headline risk.

China leads the recovery: The COVID-19 pandemic has hurt economies around the world, but developing economies appear to have suffered less of a setback as the lockdowns have not been as long-lasting. In Asia, early and stringent clampdowns stemmed the virus. China, in particular, has experienced a relatively rapid recovery in economic activity, and it should benefit from fundamental and technical tailwinds. Prudent moves by the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) during the COVID crisis provided adequate support to markets but left enough policy levers available if further easing is required. It appears, however, that additional measures may not be necessary. China’s growth rate has improved over the past few months following higher reported levels of electricity and commodity consumption. While data from China should always be taken with a grain of salt, we consider these improving numbers to be directionally correct. Given China’s intra-regional trade, and as a major consumer of commodities, China’s speedy recovery has a positive feedback loop on the emerging markets.

The experience in Latin America has been more mixed. The widespread availability of COVID-19 vaccines will likely strengthen economic growth in EM countries; we acknowledge, however, that logistical and budgetary challenges related to distributing the vaccine could dampen the immediate impact. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) forecasts EM growth of approximately –3% year-on-year for 2020, rebounding to +6% in 2021, compared to forecasts of about –6% in 2020 and +4% in 2021 for developed economies.

The challenges

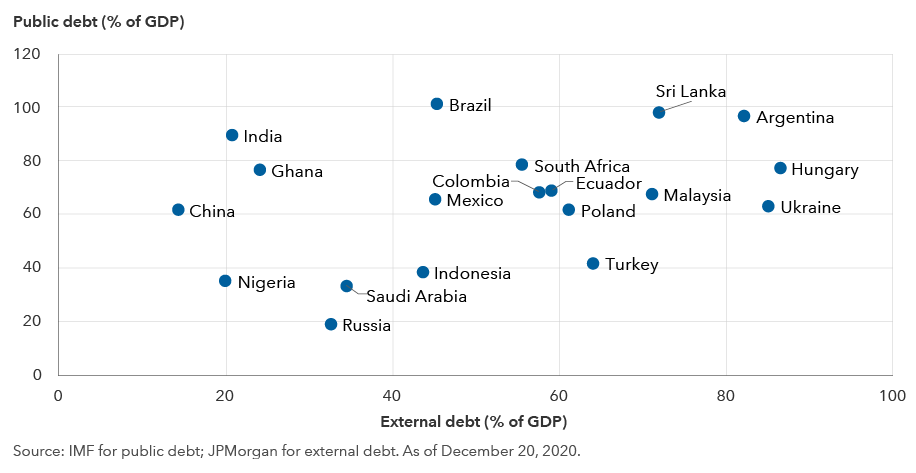

High debt burdens: In the run-up to the global financial crisis, most EM economies had broadly balanced budgets. After a decade of weak growth and falling commodity prices, many have been forced to increase fiscal spending, especially since the onset of the pandemic. As a result, public debt levels have started to rise and there is a real risk of an escalating and unsustainable debt burden in some nations. Countries like China and India have large fiscal deficits but also have the benefit of relatively strong external balance of payments. But others such as Brazil and South Africa have seen their local currency debt curves steepen, partly due to high fiscal burdens. (Long-term yields tend to go up as investors demand higher compensation for the higher risk of holding bonds of sovereigns with large deficits and high debt obligations.)

Despite the risks associated with higher debt burdens, international capital markets have generally been open to EM sovereigns, helped by investor demand for higher yielding assets, selective funding from institutions like the IMF and liquidity support from major international banks. While many governments have built up enough foreign exchange reserves for the currency risk to be limited, they remain vulnerable to global liquidity risk dynamics given a large proportion of the debt is held by international investors.

Fiscal and external debt vulnerability in emerging markets

Vulnerable credits: The broadening of EM bond markets over the past 10 years has seen many new borrowers come to market, particularly in frontier markets. This has led to increased government external borrowing, with currency weakness also contributing to a rise in external debt as a percentage of government debt for many countries. Debt restructurings have occurred in Argentina, Ecuador, Lebanon, Venezuela and Zambia, while South Africa, India, Mexico, Brazil and Colombia have seen their credit ratings downgraded. The baseline economic profile of many of these EMs leaves them with little room to withstand new shocks, so greater differentiation among credits and active management will be critical.

Reform fatigue: Several emerging economies in Latin America and Africa are growing at rates below their full potential due to lack of reforms, weak investment and poor macroeconomic policies. The first wave of reforms, implemented in the 1990s and early 2000s, included the adoption of floating exchange rates, creation of relatively independent central banks, management of runaway inflation and reduction of trade barriers. But the more difficult structural reforms such as flexibility in the labor market, land reform, streamlined taxation policies and stronger governance have been harder to implement.

Inflation: Despite the disinflationary trends that preceded the pandemic and given expectations of an extended period of low policy rates, many developing economies could see prices rise for food, housing and other essentials in 2021 — items that make up a large portion of their inflation basket. The question is whether this inflationary cycle will turn out to be a cyclical pop or something more enduring.

The investment opportunities

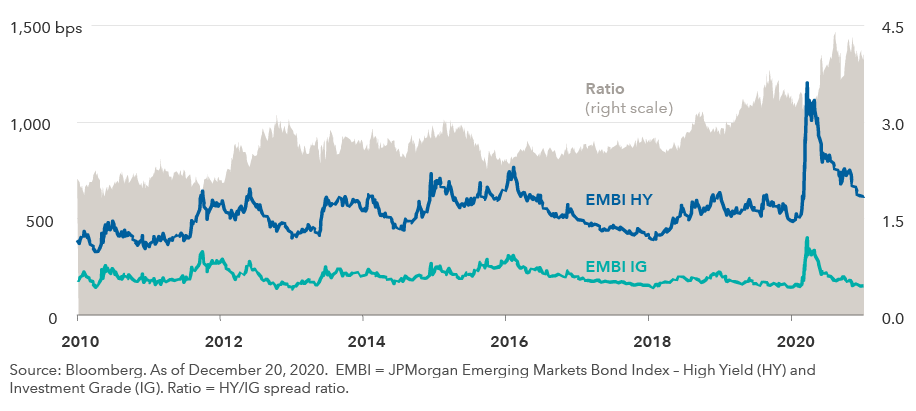

Against this backdrop, investors have shown a preference for higher quality EM debt. Not only did the lower quality, higher yielding bonds sell off more in the market decline in March and April 2020, but investment-grade EM bonds have also recovered far more than the higher yielding debt. While spreads are unlikely to fully recover anytime soon, the demand for yield beyond the “velvet rope” of Fed purchases should spill over into emerging markets. Many sovereigns have issued debt at yield levels that are attractive to them from a funding perspective, many have pre-funded their 2021 obligations and demand for these new issues has mostly been strong.

Higher yielding spreads haven’t fully recovered

Emerging markets with more positive outlooks include China, which has recently been added to the Bloomberg Barclays Global Aggregate Bond Index as the index’s fourth-largest component. This should provide a very strong technical tailwind for China’s bond market. Malaysia, with its diversified economy, is another Asian country that is recovering relatively quickly. Malaysia runs a trade surplus, a common factor across the Asian countries that should continue to provide support to its sovereign debt valuations.

Currencies: Most EM currencies have lost value against major currencies of developed economies over the past decade, partly due to macroeconomic dynamics specific to each country, but also as many EM central banks steadily cut domestic interest rates. However, since November 2020, EM currencies have posted strong returns against the backdrop of a Biden election victory and positive news on vaccines. Our model calibrating several fundamental factors suggests that most EM currencies remain undervalued. Should the U.S. dollar move into a period of steady decline, a broad basket of EM currencies will likely benefit.

Returns have varied across EM debt sub-asset classes

Overall, we see value in a portfolio that can take a balanced approach to combining investment-grade sovereigns, investment-grade corporate bonds (especially those related to commodities) and select higher yielding credits with an improving macroeconomic profile.

The varying trajectories among EM countries highlight the fact that EM debt represents a wide opportunity set. It has evolved into a mature asset class comprised of 75 countries and more than $4.5 trillion in assets. Investors willing to absorb somewhat higher volatility in fixed income portfolios can benefit from a potentially substantial pickup in yield over developed markets, but active management remains key.

The return of principal for bond funds and for funds with significant underlying bond holdings is not guaranteed. Fund shares are subject to the same interest rate, inflation and credit risks associated with the underlying bond holdings.

The use of derivatives involves a variety of risks, which may be different from, or greater than, the risks associated with investing in traditional cash securities, such as stocks and bonds. Lower rated bonds are subject to greater fluctuations in value and risk of loss of income and principal than higher rated bonds.

Investing outside the United States involves risks, such as currency fluctuations, periods of illiquidity and price volatility, as more fully described in the prospectus. These risks may be heightened in connection with investments in developing countries.

Bloomberg® is a trademark of Bloomberg Finance L.P. (collectively with its affiliates, “Bloomberg”). Barclays® is a trademark of Barclays Bank Plc (collectively with its affiliates, “Barclays”), used under license. Neither Bloomberg nor Barclays approves or endorses this material, guarantees the accuracy or completeness of any information herein and, to the maximum extent allowed by law, neither shall have any liability or responsibility for injury or damages arising in connection therewith.

Bloomberg Barclays Global Aggregate Index represents the global investment-grade fixed income markets.

This report, and any product, index or fund referred to herein, is not sponsored, endorsed or promoted in any way by J.P. Morgan or any of its affiliates who provide no warranties whatsoever, express or implied, and shall have no liability to any prospective investor, in connection with this report. J.P. Morgan disclaimer: https://www.jpmm.com/research/disclosures

JP Morgan Emerging Markets Bond Index – Global tracks total returns for U.S. dollar-denominated debt instruments issued by emerging markets sovereign and quasi-sovereign entities, including Brady bonds, loans and Eurobonds.

The J.P. Morgan Emerging Market Bond Index (EMBI) Global Diversified is a uniquely weighted emerging market debt benchmark that tracks total returns for U.S. dollar-denominated bonds issued by emerging market sovereign and quasi-sovereign entities.

JP Morgan Government Bond Index – Emerging Markets Global Diversified covers the universe of regularly traded, liquid fixed-rate, domestic currency emerging market government bonds to which international investors can gain exposure.

J.P. Morgan Emerging Markets Bond Index is a market-capitalization weighted index consisting of U.S. dollar-denominated emerging markets bonds issued by sovereign and quasi-sovereign entities, including Brady bonds, Eurobonds and traded loans.

J.P. Morgan Corporate Emerging Markets Bond Index (CEMBI) is a market-capitalization weighted index consisting of U.S. dollar-denominated debt instruments issued by corporate entities in emerging markets countries.

The indexes are unmanaged and, therefore, have no expenses. Investors cannot invest directly in an index.

Our latest insights

-

-

Emerging Markets

-

Global Equities

-

Economic Indicators

-

RELATED INSIGHTS

-

-

Emerging Markets

-

Economic Indicators

Don’t miss out

Get the Capital Ideas newsletter in your inbox every other week

Rob Neithart

Rob Neithart

Kirstie Spence

Kirstie Spence

Harry Phinney

Harry Phinney