Emerging Markets

China

The first 100 days in power for any new presidential administration is never easy. With U.S.-China relations at arguably their lowest point in 50 years, the administration of President Joe Biden will have to make some difficult policy decisions that could affect the balance of the world’s two largest economies. How could the relationship evolve over the next four years?

We asked Capital Group political economist Michael Thawley and portfolio manager Chris Thomsen to share their perspectives on potential implications for trade policies and investments.

How much might policy change under the Biden administration?

Michael Thawley, political economist: The Biden administration is facing the same problems as the Trump administration, so I don’t expect much change from a geopolitical standpoint. China’s economy is currently the single greatest contributor to global growth and its leaders have grown more self-confident and are seeking a greater voice in world affairs.

I think the overall policy framework will carry over with a few caveats. I anticipate the existing trade tariffs will remain in place for the foreseeable future. Biden’s team will probably maintain the investment and technology restrictions against China but try to define them more carefully and create more streamlined and predictable processes. This could help certain U.S. technology companies and Wall Street banks that have investments and interests in China.

For example, some of America’s leading semiconductor companies count China among their largest markets for sales. If they are restricted in shipping more advanced chips to China, this could affect their longer-term revenue. Meanwhile, Wall Street banks and asset managers want to make a bigger push into China after Beijing loosened rules to operate in the country.

Elsewhere, coalition-building and mitigating climate change are part of Biden’s global agenda. This is a significant departure from the priorities of the past four years. Another shift might be more targeted sanctions when it comes to China’s policies toward Hong Kong and Taiwan. This is an ongoing risk.

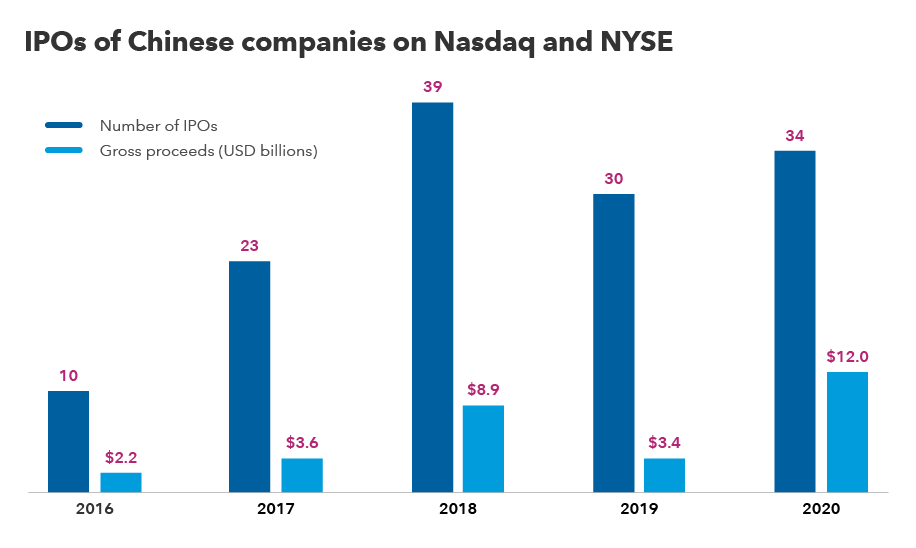

The U.S. has remained an IPO destination for Chinese companies

Source: FactSet. As of December 31, 2020.

What do you see as potential challenges to this approach?

Thawley: The Biden team will aim to rehabilitate alliances with allies and work more consistently with these other countries on China. While the previous administration was viewed as taking a unilateral approach, Biden will be challenged in forming an international coalition to influence China in hopes of reaching a new equilibrium.

It won’t be easy to craft policy that allows for mutually beneficial economic cooperation while at the same time limiting the pressure China can put on the U.S. and its allies.

South Korea, Japan and Australia are looking to the United States to help balance China’s power in the Western Pacific. It's complicated, because everyone has huge economic interests in their relationship with China. The U.S. and its allies still want to do business with China and investors want to invest there.

The Biden administration could seek an arrangement with China that acknowledges its importance to the world economy. This could result in fairer economic practices and a level playing field. From my experience working in government, I’ve found that creating and sustaining coalitions behind such a set of common goals can be hard work.

Could this herald a greater decoupling of the two economies?

Thawley: I don’t think a decoupling will happen. It would not be in the best interests of the U.S. or the world. The U.S.-China economic relationship will still be substantial, but much more focused in areas where there is less concern about technology transfer and intellectual property, such as agricultural products and basic consumer goods.

In the past, the U.S.-China economic relationship was fueled by business investment and technology transfer. That has changed and will continue to evolve. Current restrictions are also going to limit the amount of economic and commercial integration of corporations. This would affect both U.S. and Chinese companies. For instance, some top U.S. exports to China are semiconductors, aerospace products and motor vehicles.

The Biden administration will likely make the investment and technology restrictions on China more systematic and targeted. This approach could provide more clarity and predictability to economic interaction between them. And I expect U.S. officials will remain preoccupied with cyber issues, protection of personal and consumer data and critical infrastructure.

At this juncture, we are probably looking at a bifurcated world in terms of the internet and manufacturing. It’s clear that the U.S. won’t be importing 5G cellular technologies from China or exporting our most advanced technologies there.

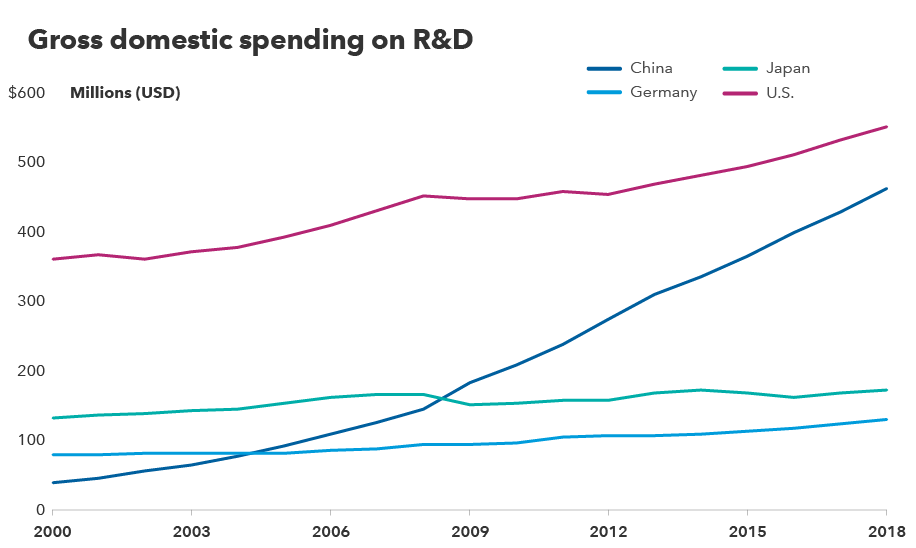

China is evolving from the world’s factory to innovative growth

Source: OECD.

What does this mean for strategically important areas like technology from a bottom-up perspective?

Chris Thomsen, portfolio manager: In technology, the world is bifurcating into two separate systems: one centered around China and the other around the U.S. and its allies. In telecommunications hardware, this is already happening in 5G: China is ahead of the U.S. in developing its network, and the U.S. and many European Union countries have banned Huawei from their telecom networks.

Semiconductors is another complicated area. Companies are being forced to navigate new trade rules and position themselves to meet customer demand in the U.S. and China. TSMC, the world’s largest contract chipmaker, plans to build a world-class manufacturing plant in Arizona, and some of its suppliers are weighing similar investments on American soil. At the same time, a leading Korean memory chipmaker is moving some of its manufacturing capacity for lower end chips to China.

China wants to become self-sufficient in key industries, and for that reason developing the semiconductor industry is a critical component of the government’s five-year plan. Currently, companies in China that make mobile phones and other electronics rely heavily on Taiwan, Korea and the U.S. for more advanced semiconductors and manufacturing equipment.

Even though Chinese companies like Tencent and Alibaba have created world-leading mobile payment and internet services platforms, the country lags the rest of the world in semiconductors and is many years away from having cutting-edge technology to compete in certain areas, including memory chips and leading node semiconductor equipment. For example, China's top chipmaker is producing chips on 14-nanometer process technology, which is at least two generations behind the global market leader. Given geopolitical uncertainties, China’s government is providing substantial financial incentives for both state-backed and privately run semiconductor companies to close the technological gap.

How are U.S.-China relations shaping your investment perspective?

Thomsen: The selective decoupling and strategic competition between the U.S. and China will likely last for the rest of my investing career. And while it can be easy to lose sight of long-term secular trends and potential investment opportunities when tensions flare up, China has significantly evolved from the state-planned economy of the 1980s and being the factory of the world in the 1990s and 2000s.

Despite negative headlines about trade wars, I’m confident China will remain one of the most attractive investment opportunities in the world due to its young and vibrant population and an increasingly educated and talented middle class.

Today China is home to many entrepreneurial and innovative companies. And the enormous domestic market enables successful winners to scale up exponentially. In my portfolio, many of the larger Chinese holdings weren’t even listed a decade ago.

The trade war has reinforced China’s focus on its domestic economy. Under China’s new “dual circulation” strategy, Beijing wants to vertically integrate and insulate its economy by building reliable domestic supply chains that can serve its industries and be an alternative source for a wide range of products and services.

I’ve avoided areas affected by the trade conflicts, such as exporters or state-run companies, which tend to be low-return businesses. Instead, I have focused on private sector companies that might become tomorrow’s national champions in areas of technology, services, health care, and the ever-evolving middle-class consumer. Hopefully these companies will be relatively insulated from global trade tensions and benefit from attractive secular trends.

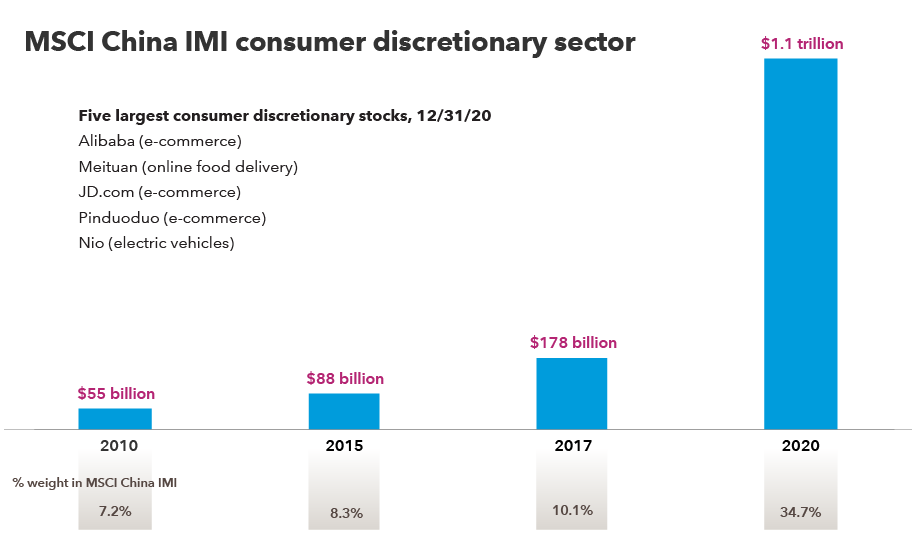

A surge in value for China’s consumer discretionary companies

Sources: RIMES, MSCI. Data reflects market cap of MSCI China IMI consumer discretionary sector as of December 31, 2020.

Where do you see potential growth areas in China?

Thomsen: The biopharmaceuticals industry is one example. The industry barely existed 10 years ago in China, but now there are several publicly traded firms with market values north of $30 billion.

Local biopharmaceutical companies have gained international credibility among multinational pharmaceutical giants that want to work with them to develop, test and manufacture drugs. Two of the key drivers for this evolution have been the large influx of scientists returning to China from abroad and the surge in venture funding for health care startups.

The service side of the Chinese economy has been rapidly developing, and I have been focused on investment ideas that target domestic businesses or consumers.

Take enterprise software. China has lagged the U.S. in adopting cloud-based technology. Corporations viewed software as a cost rather than a productivity tool, but today more Chinese companies are investing in and adapting software as a service.

Rising wealth among China’s consumers is opening up a number of potential investment opportunities. We’ve seen strong demand for better health care, and private hospital chains offering specialized medical procedures have significant growth potential.

As China’s car market continues to mature, I’m interested in auto dealer networks that have strong relationships with global manufacturers and are consolidating a fragmented industry. They should benefit from the sale of new cars and can also capture the high-margin after-sales service business for repairs and maintenance as well as used car sales.

The most exciting area has been the internet space.

Alibaba and Tencent initially copied U.S. peers but have since evolved into incredibly sophisticated multifaceted platforms. But today they could be viewed as the first-generation of Chinese internet companies.

There’s been a new wave of innovative second- and third-generation companies run by dynamic entrepreneurs. These companies have scaled up incredibly fast due to the size and technological sophistication of China’s market. In my view, it’s extremely difficult to find these types of opportunities outside of China, and I enjoy hunting for these new ideas for my portfolio.

Investing outside the United States involves risks, such as currency fluctuations, periods of illiquidity and price volatility. These risks may be heightened in connection with investments in developing countries. Small-company stocks entail additional risks, and they can fluctuate in price more than larger company stocks.

MSCI has not approved, reviewed or produced this report, makes no express or implied warranties or representations and is not liable whatsoever for any data in the report. You may not redistribute the MSCI data or use it as a basis for other indices or investment products.

The MSCI China IMI captures large-, mid- and small-cap representation of approximately 99% of the investable equity universe for mainland China's market. There are 945 constituents as of February 26, 2021.

Our latest insights

-

-

Global Equities

-

Economic Indicators

-

-

Manufacturing

RELATED INSIGHTS

-

Emerging Markets

-

Global Equities

-

Economic Indicators

Never miss an insight

The Capital Ideas newsletter delivers weekly insights straight to your inbox.

Michael Thawley

Michael Thawley

Christopher Thomsen

Christopher Thomsen