Trade

The fragility of global supply chains exposed during the COVID-19 pandemic remains one of the top economic challenges facing the world. In one respect, globalization has long been characterized by developed market countries offshoring production to lower cost locations. But now, companies are recognizing the need to build redundancies into their supply lines, which will have varied impacts on countries, companies and industries.

While some have argued this could lead to a less globalized world or “deglobalization,” this could be the start of an era of “reglobalization," in which supply chains are reorganized and more countries are brought into global trade networks.

“I would expect most companies with a significant percentage of their manufacturing base in Greater China (including Taiwan) to diversify to other countries,” says Noriko Chen, a Capital Group equity portfolio manager with New Perspective Fund®. “The reinvestment in some countries is likely to be positive. But it will also come at a cost to profitability for some companies. However, this should lead to new investing opportunities for those who can identify companies that will benefit from changes in global trade patterns.”

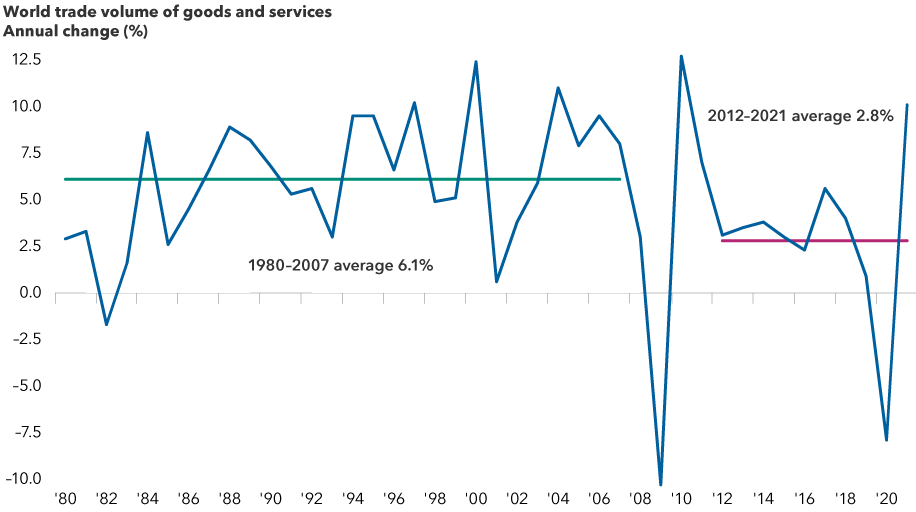

Global trade has slowed but is still growing

Sources: International Monetary Fund, Refinitiv Datastream. As of December 31, 2021.

Supply chains are shifting but not deglobalizing

Many companies are shifting their areas of manufacturing operations to multiple centers across the globe to disperse risk. That does not necessarily mean this could result in less economic integration. Consider Taiwan-based TSMC, the world’s dominant manufacturer of cutting-edge semiconductors. After having concentrated the bulk of its capacity in Taiwan — a focal point of geopolitical tensions — TSMC is building its first manufacturing hub in the United States. It’s also constructing a new semiconductor plant in Japan.

Multinationals with a significant presence in China are also looking for that next big opportunity to reach consumers outside of China. Apple, which has arguably built the most impressive supply chain of any multinational in China, moved some iPhone production to India, which is forecast to have an estimated 1 billion smartphone users by 2026.

There are also Chinese companies seeking to forge closer trade links with their customers outside of China. Chinese electric vehicle (EV) battery maker CATL (Contemporary Amperex Technology Co.) recently received approval to build a battery cell plant in Germany, where it works with the top German automakers.

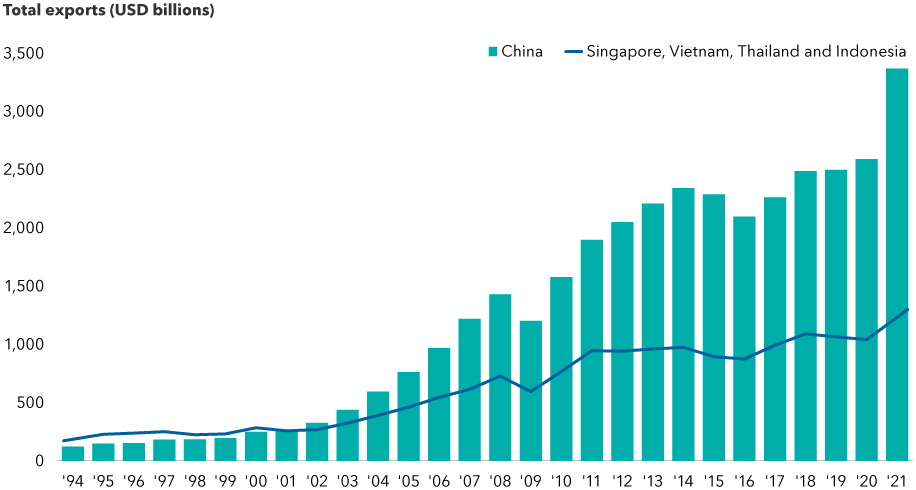

Diversification from China will take time

For those companies reducing their dependence on China, the diversification from China’s supply chain will take time. China is likely to remain significant due to a lack of viable alternatives and because more goods made in China will increasingly target Chinese consumers in the future.

“A common phrase I hear from companies is ‘China Plus,’” says Ben Lin, an investment analyst at Capital Group. “This means manufacturers will retain their existing China factory, but will gradually add production capacities outside of China and slowly build up the domestic supply chain in those countries. This could take at least several years or even a decade before they can replace Chinese suppliers.”

China's export sector dwarfs Southeast Asian rivals

Sources: Capital Group, Refinitiv Datastream. As of December 31, 2021. Values are not adjusted for inflation.

For now, China remains one of the world’s top destinations for foreign direct investment flows, which reflect companies buying, building or reinvesting in operations abroad. In 2021, China ranked second behind the U.S., with $334 billion of flows, according to data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

Multinationals still see value in tapping into China’s large and skilled workforce. A case in point is Tesla. China has become a key production hub for the dominant EV maker. Tesla opened its Shanghai gigafactory in 2019 to help boost its annual car production and increase its global market share by selling to the world’s top consumer of EVs.

Another area is health care. Pharmaceutical giants such as AstraZeneca and Pfizer have built strong relationships with domestic Chinese biopharmaceutical companies to help develop and test new drugs. Clinical trials account for approximately 90% of the cost of developing a drug for global use, and labor costs for clinical trials are cheaper in China compared with the U.S., Germany and Switzerland, according to Capital Group analysts who cover the health care sector.

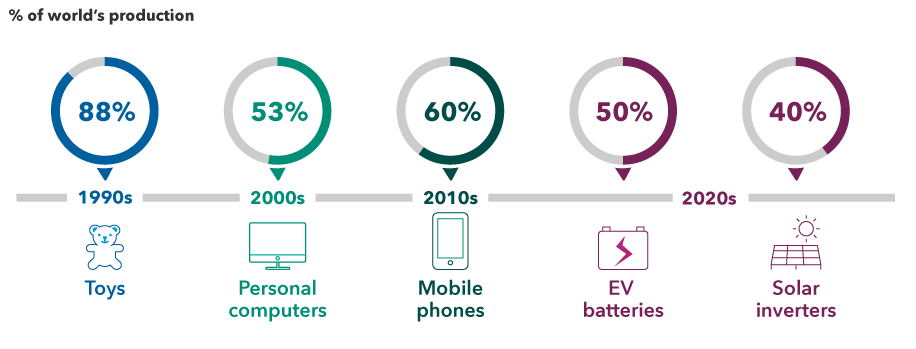

China has moved up the manufacturing value chain

Source: Capital Group, based on reports from Euromonitor, SNE Research and company filings. Data as of May 2021 and reflect approximate figures.

Building security and redundancy in supply chains

The global supply chain has been under unprecedented stress, from the U.S.-China trade war to the COVID-19 pandemic to the war in Ukraine. If any industry has felt the brunt of the supply chain snarls, it’s been the auto business.

General Motors, Ford, Stellantis and other global automakers have faced steep production cuts, resulting in a scarcity of vehicles on dealer lots and a sharp increase in the prices of new and used cars. This is leading to structural changes within the auto industry, which has had to entirely rethink its supply chains.

One outcome has been a move away from receiving “just-in-time” inventory to holding “just-in-case” inventory when it comes to semiconductors.

Building redundancies in supply chains will come with opportunities and challenges. Certain industries will be beneficiaries, ranging from those supplying semiconductor equipment and industrial components to automation tools and physical metals.

“I anticipate reshoring to be a major growth driver for select industrial companies over the next five to 10 years,” says Capital Group equity investment analyst Gigi Pardasani. “Many U.S. industrials are investing at levels we have not seen since the early 2000s to better position themselves to meet this demand.”

In the near term, there will be financial costs and potential ramifications of supply chain shifts, such as:

Greater levels of corporate spending and higher operating costs. For Western companies moving production back to their home markets, or for Asian companies expanding their footprint into the West, the costs will be higher than running factories solely in China or other Asian countries. Companies are likely to either pay for more expensive automation equipment or higher wages for workers.

Higher costs for consumers. Inflation is already running at a 40-year high in the U.S. as higher prices ripple through global supply chains. Higher costs for companies to build more inventories or reshore manufacturing are likely to translate into higher prices for consumers. Companies will absorb some, but not all, of the costs, which could weigh on consumer demand for their products.

Higher working capital needs and operating margin pressure due to costs associated with building redundancy and flexibility in supply chains. These factors could weigh on future margins and valuations for companies. Lower returns on invested capital may be here to stay as a result of a change in the geopolitical landscape and central banks’ rate policies.

“Companies and businesses with pricing power or economies of scale may benefit from this environment, but those without these advantages may face profit margin and earnings pressure and potentially lower valuation multiples,” says Kent Chan, an equity investment director at Capital Group.

However, he adds, there’s the possibility that “those companies that are able to diversify sourcing and build greater security and resilience in their supply chain may be rewarded with a higher valuation longer term, in spite of the costs.”

Opportunities from global shifts in production

Looking at modern history, this is not the first time the global supply chain has been realigned.

In the early 1990s, Hong Kong was a hub for textiles, and Taiwan was a large manufacturer of sneakers. That gradually changed when China set up special economic zones, luring manufacturers with a more affordable option.

“Not only did these shifts in the supply chain not harm the economies of Hong Kong and Taiwan, but rather created room for the evolution of their respective economies,” recalls Chan, who worked in Hong Kong in the 1990s. “Over time, Hong Kong overtook Tokyo to become Asia’s leading financial services hub, and Taiwan moved up the value curve to become the world’s dominant manufacturer of semiconductors.”

This is a reminder that, despite worries around supply shortages, fears of deglobalization and the expected shift in global supply chains, new opportunities could emerge in the regions where production is shifting, as well as in those countries where production is leaving.

Investing outside the United States involves risks, such as currency fluctuations, periods of illiquidity and price volatility. These risks may be heightened in connection with investments in developing countries.

Our latest insights

-

-

Emerging Markets

-

Global Equities

-

Economic Indicators

-

RELATED INSIGHTS

-

Global Equities

-

-

Manufacturing

Never miss an insight

The Capital Ideas newsletter delivers weekly insights straight to your inbox.

Noriko Chen

Noriko Chen

Ben Lin

Ben Lin

Kent Chan

Kent Chan