Economic Indicators

Japan

The story of Japan overcoming its Lost Decades is deep and fascinating. In addition to this analysis by Capital Group economist Anne Vandenabeele, you can read how recent economic reforms could lend resilience to this upswing, by equity analyst Sean Tian; an examination of how cultural and rules changes might boost markets by equity analyst Shintoku Nishiwaki; and a look at the positives of inflation and the “ramen index” by equity portfolio manager Kohei Higashi.

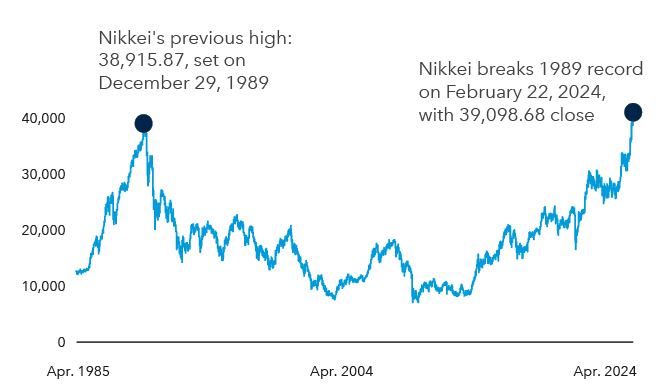

When Japan’s Nikkei stock index broke records this year, investors had more than one reason to cheer. While a new high was cause for celebration in itself, the milestone underscored a far grander accomplishment: after more than three decades of failed rallies that reflected the country’s perennial economic woes, the index had finally climbed back to the heights it achieved in 1989.

While all major economies experience ups and downs, few have endured the heart-pounding extremes of Japan. The economy boomed after World War II, thanks to a powerful combination of postwar infrastructure spending and loose economic policy. By 1968, Japan claimed the mantle of the world’s second-largest economy.

The heyday came in the late 1980s, when the country and its leading businesses were heralded for their supposed technological prowess, cutting-edge management techniques and economic momentum. Japanese companies scooped up trophy U.S. assets such as Rockefeller Center, Columbia Pictures and the Pebble Beach golf course.

Nikkei surpasses previous high

Source: St. Louis Fed. Nikkei is represented by the Nikkei 225, a price-weighted index covering 225 large Japan-based businesses. Results are from March 31, 1985, through March 31, 2024. As of April 1, 2024.

But the economy dissolved into a tailspin soon thereafter. Interest rates that remained low even as the country became built out helped inflate twin stock market and real estate bubbles that burst with devastating consequences in 1990. The economic crisis would have been sharp on its own, but it was exacerbated by a sluggish government response, an aging population and shellshocked corporations that prioritized resiliency and saw little need to invest in such a bleak environment. Together, these forces resulted in a “lost decade” of deflation and below-trend growth that proved stubborn enough to become “lost decades.” Japan became a cautionary tale for developed economies.

Japan’s comeback appears to have staying power.

That’s why there was so much enthusiasm in February when the Nikkei, an analog to the S&P 500 in the U.S., surpassed the 38,915.87 closing record first set on Dec. 29, 1989. The big question: Could this surge, unlike the other upturns over the last 34 years, be the first sign that Japan’s fortunes are turning a corner? The short answer: I think so.

Japan’s equity market is far less expensive, on a relative basis, than those of many other developed nations — giving it room to run. And many of the forces that marked the lost decades have shown signs of relenting: Price growth has pulled out of deflation territory, staying positive since late 2021; Japanese companies are exploring ways to improve their efficiency; and common labor practices are changing, empowering employees to pursue better-paying jobs at dynamic companies and industries. Additionally, new technologies are providing a welcome productivity boost.

To be sure, there’s no assurance that this uptick won’t flame out like so many others have since 1990. Many Japanese corporations still pursue inefficient practices that are considered poor governance elsewhere, such as owning each other’s shares and limiting board independence. The government is in a transitional period, which could limit how much energy it can spare in the near term for economic policy and support. And, of course, much still depends on the overall direction of the nation’s economy, which has sputtered in recent months. Long ago overtaken by China in the ranking of world economies, Japan recently slipped to fourth place, behind Germany.

Still, on balance, the changes sweeping Japan are heartening.

Cultural and technological evolution could begin to outweigh stubborn negative trends.

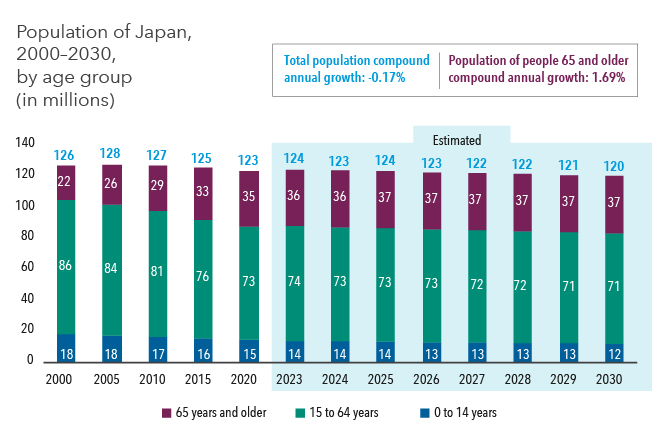

One of the most enduring through lines in modern Japan has been its aging population. Even today, birth rates are still well below replacement, and the population has been steadily shrinking since 2011. In a broad sense, this weighs on GDP — there are fewer people buying things, after all.

An aging population is boosting Japan's younger workforce

Source: Statista, Capital Group. Population total for 2023 and later are estimates. As of November 2023.

However the aging population can have some counterintuitively positive effects. Japan’s workforce has been shrinking since the start of the century, and it’s experienced chronic labor shortages for some time. Young people commonly fill entry-level jobs and physically demanding work, so as they become a smaller share of the population, supply for that kind of labor falls.

As a result, employers are paying more to attract and retain talent. That inflationary condition would be a source of consternation in many countries. But not in Japan, which has grappled with deflation for many years. Modest inflation could give businesses all-important pricing power.

Beyond that, young people are flexing their might in interesting ways, prompting potentially long-lasting changes in employment and lifestyle. Some are flouting old expectations of settling into lifetime employment with a single firm, instead opting to move between companies and industries in pursuit of better opportunities. Startups and consulting are becoming more common as well. These all have positive impacts on corporate dynamism, productivity and efficiency, as the young aren’t being trapped in stagnant or low-performing businesses.

Additionally, an older population will have more retirement-age people. The median age of a small- and mid-size company owner in Japan is 67, likely setting up a wave of retirements in the next several years. That’s going to result in a lot of shuttered and sold businesses, which could create efficiency gains through acquisitions, as well as opportunities for remaining businesses to increase market share.

Add in productivity gains due to digital transformation, including artificial intelligence. Payment systems, back-office automation and other advancements are helping address labor shortages and further freeing workers to pursue better jobs.

Taken together, these forces have the potential to spur a virtuous cycle, with wage gains feeding into consumer spending and healthy inflation, productivity gains powering corporate revenue and a rosier outlook coaxing businesses to invest more in their workforces and infrastructure.

Corporate governance improvements are bearing fruit.

One of the more notable changes in recent years has been the push for greater corporate governance. At the prodding of both the government and the Tokyo Stock Exchange, companies have slowly embraced shareholder-friendly reforms. They’re digging into their corporate coffers to boost capital investment and stepping up outlays on dividends and stock buybacks.

Despite concerns about the future of globalization, I think the earnings growth for Japanese businesses looks promising thanks to improved domestic productivity and better pricing power amid modest inflation.

The bottom line is that many of the impediments that constrained Japan for many years are changing for the better, which suggests to me a much more upbeat outlook for equity returns over the next five to 10 years.

If you found this story intriguing, consider reading through our additional stories on Japan: How reforms could lend resilience to this upswing, by equity analyst Sean Tian; an examination of how cultural and rules changes might boost markets by equity analyst Shintoku Nishiwaki; and a look at the positives of inflation and the “ramen index” by equity portfolio manager Kohei Higashi.

Anne Vandenabeele

Anne Vandenabeele