Market Volatility

Election

Benjamin Graham, the father of value investing, famously noted that “In the short run, the market is a voting machine but in the long run, it is a weighing machine.” He wasn’t referring to the intersection of elections and investing, but the saying applies just as well. Markets can be especially choppy during election years, with sentiment often changing as quickly as candidates open their mouths.

Graham made his analogy in 1934 in his seminal book “Security Analysis.” Since then there have been 23 election cycles, and we’ve analyzed them all to help you prepare for investing in this potentially volatile period. Below we highlight three common mistakes investors make in election years and offer ways to avoid these pitfalls and invest with confidence in 2024.

Mistake #1: Worrying too much about which party wins

There’s nothing wrong with wanting your candidate to triumph, but investors can run into trouble when they place too much importance on election results. That’s because elections have, historically speaking, made essentially no difference when it comes to long-term investment returns.

“Presidents get far too much credit, and far too much blame, for the health of the U.S. economy and the state of the financial markets,” says Capital Group economist Darrell Spence. “There are many other variables that determine economic growth and market returns and, frankly, presidents have very little influence over them.”

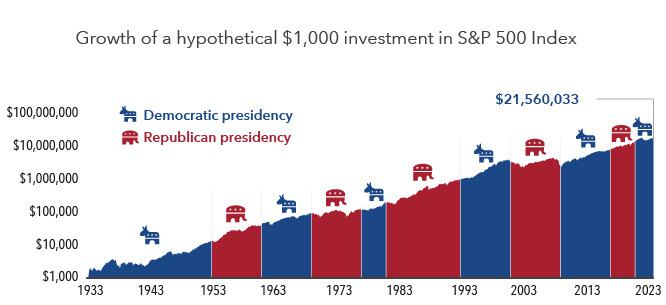

What should matter more to investors is staying invested. Although past results are not predictive of future returns, a $1,000 investment in the S&P 500 made when Franklin D. Roosevelt took office would have been worth almost $22 million today. During this time there have been eight Democratic and seven Republican presidents. Getting out of the market to avoid a certain party or candidate in office could have severely detracted from long-term returns.

Regardless of who held the White House, markets have historically grown over the long term

Sources: Capital Group, Morningstar, Standard & Poor’s. As of December 31, 2023. Dates of party control are based on inauguration dates. Values are based on total returns in USD. Shown on a logarithmic scale. Past results are not predictive of results in future periods.

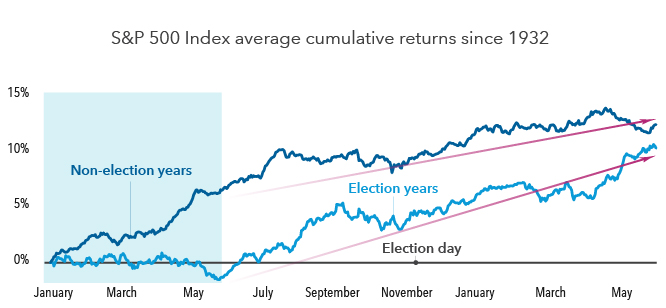

Mistake #2: Getting spooked by primary season volatility

Markets hate uncertainty, and there are few things more uncertain than primary season. That said, volatility caused by this uncertainty is often short-lived. After the primaries are over and each party has selected its candidate, markets have tended to return to their normal upward trajectory.

Election year volatility can also bring select buying opportunities. Policy proposals during primaries often target specific industries, which can weigh on share prices. The health care sector has been targeted for a number of election cycles. Heated rhetoric over drug pricing put pressure on many stocks in the pharmaceutical and managed care industries. Other sectors have had similar bouts of weakness prior to elections.

However, that doesn’t mean that you should avoid specific sectors, says Rob Lovelace, an equity portfolio manager with 38 years of experience investing through many election cycles.

“When everyone is worried that a new government policy is going to come along and destroy a sector, that concern is usually overblown,” Lovelace says.

Regardless of who won, stocks with strong long-term fundamentals have often rallied once the campaign spotlight faded. This pre-election market turbulence can create buying opportunities for investors with a contrarian point of view and the strength to tolerate what could be short-term volatility.

Historically, markets have been more volatile in the run up to an election

Sources: Capital Group, RIMES, Standard & Poor’s. Includes all daily price returns from January 1, 1932–December 31, 2023. Non-election years exclude all years with either a presidential or midterm election. Past results are not predictive of results in future periods.

Mistake #3: Trying to time the markets around politics

If you’re nervous about the markets in 2024, you’re not alone. Presidential candidates often draw attention to the country’s problems, and campaigns regularly amplify negative messages. So maybe it should be no surprise that investors have tended to be more conservative with their portfolios ahead of elections.

Since 1992, investors have poured assets into money market funds — traditionally one of the lowest risk investment vehicles — much more often leading up to elections. By contrast, equity-focused mutual funds have tended to experience their highest net inflows in the year immediately after an election. This suggests that investors may prefer to minimize risk during election years and wait until after uncertainty has subsided to revisit riskier assets like stocks.

But market timing is rarely a winning long-term investment strategy, and it can pose a major problem for portfolio returns. To verify this, we analyzed investment returns over the last 23 election cycles to compare three hypothetical investment approaches: being fully invested in equities, making monthly contributions to equities or staying in cash until after the election. We then calculated the portfolio returns after each cycle, assuming a four-year holding period.

The hypothetical investor who stayed in cash until after the election had the worst outcome of the three portfolios in 17 of 23 periods. Meanwhile, investors who were fully invested or made monthly contributions during election years came out on top. These investors had higher average portfolio balances over the full period and more often outpaced the investor who stayed on the sidelines longer.

Related Insights

Related Insights

-

How to handle market declines

-

Trade

Tariffs explained: Assessing the global economic impact -

Trade

Understanding tariffs in 5 charts