Planning & Productivity

Team Management

The most successful advisory practices all share a key ingredient: teams that are optimized for success.

Whether you work within a large enterprise firm or head a small advisory practice, you have a team in place. But is that team organized in an optimal way to serve your clients and your business? Smartly allocating your talent pool can help you provide the right services to clients while also nurturing the next generation of both advisors and clients.

Team management tends to go hand in hand with increased productivity, and high-growth advisors spend comparatively more of their time on it, according to Capital Group’s Pathways to Growth: 2022 Advisor Benchmark Study. More and more, advisors are seeing the merits of teaming. In 2007, about 15% of advisors co-managed their book of business. Today, it’s 32%, according to Cogent Advisor Brandscape.1 What’s key is that the type of team formed matches the business goals of the firm and skill sets of team members.

Are you happy with the size and focus of your current team but want to run more efficiently so that you can boost your client roster? Or maybe you want to build a team that allows you to specialize your services to fit your particular passions. Perhaps you aim to grow your current team into an enterprise that can serve as a holistic one-stop shop for all of your client needs.

Here are three ways to approach building a team focused on specific practice goals: boosting productivity, offering specialized services or becoming a one-stop shop for all client financial needs.

Vertical teams: A top-down team structure can help accelerate productivity

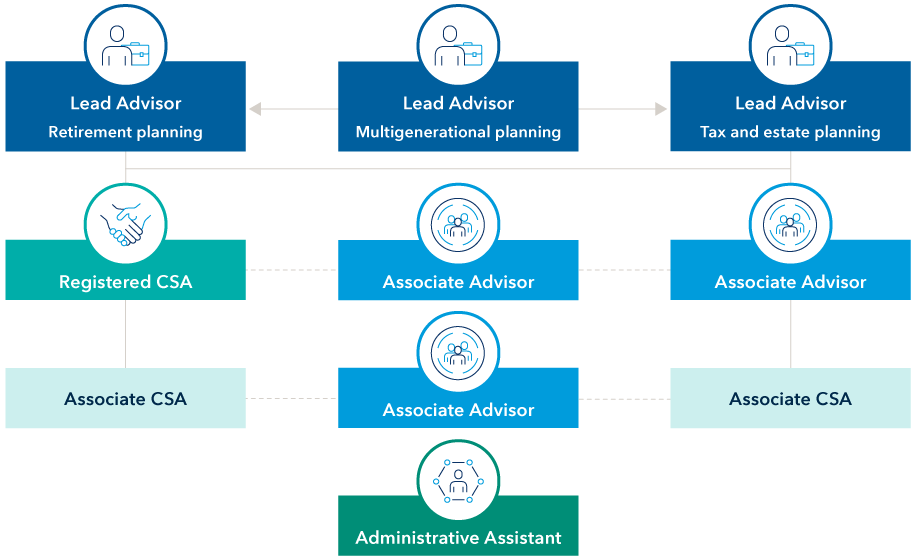

Vertically aligned teams can be appropriate for the advisor who wants to maintain control of the client relationship and investment decisions but also wants to grow her practice operationally. This team structure places the lead advisor at the top of the organizational chart, with associate advisors and support staff falling in line below them.

For example, a solo practitioner relying on operational support from client service associates or paraplanners would be considered a vertically aligned organization.

Team members in support roles handle duties such as client onboarding and paperwork or facilitating the creation of financial plans, freeing up the lead advisor’s time to focus on client-facing activities. But while the roles in this team structure are supportive in nature, they can still be well-defined. To maximize the potential productivity in this team structure, it’s important that each person has a clear idea of who does what and how those activities fit into the firm’s overall goals and operations.

“It’s critical that your team is clear on what good looks like,” says Michael Schweitzer, head of High Net Worth at Capital Group. “High-performing teams have defined each role with respect to what success looks like.”

A vertical team structure could be led by the advisor, who is responsible for new client acquisition, portfolio reviews and analysis, and wealth management. Associate advisors and specialists are positioned directly below to provide support in marketing, research and due diligence and expertise in insurance, tax or estate planning. Client service associates and administrative assistants focus on the daily tasks that keep the firm running.

Vertical teams offer advisors a streamlined approach to running their practice

Source: Capital Group

Incentivizing vertical teams

It is important that advisors leading these types of teams have a plan to keep their team motivated. In such a top-down structure, it’s the lead advisor that gets credit for the “wins,” so making sure your employees are motivated — including financially — is important. One way to do so is to make sure you’ve developed a plan for employees’ career development. “Some advisors think, if I invest in my people and they get better, they might leave me, but actually the opposite happens,“ Schweitzer says. “Investing in them often creates more loyalty. And as they develop their skills and become more valuable, they can create a lot of enterprise value for the team.”

Schweitzer also recommends that advisors think creatively when it comes to compensation. One idea is to give employees what he calls “phantom equity,” where they don’t actually own a percentage of the business but receive bonus pay as if they did. “Advisors can structure that compensation on areas of the business they want to grow,” such as fee-based offerings, he says. “It’s got to be well-defined, so the employee knows exactly what they need to do to earn that bonus.”

For inspiration, he suggests looking at rocker Jon Bon Jovi. “The equity of the franchise, the band Bon Jovi, is all with Jon Bon Jovi and he paid people to play with him,” Schweitzer says. “He made them very wealthy as a result of the success of the business, but they never owned any part of the franchise, per se.”

Generally, advisors leading vertical teams also may find that they have to spend more time managing the day-to-day business and have less bandwidth for targeted marketing and acquisition activities. They may also be less likely to offer a breadth of personalized planning services. But building a robust centers-of-influence (COI) network can help fill that gap, enabling you to provide clients with specialized services while also prospecting for new referrals.

Takeaway: Vertical teams give you control of your firm’s operations and vision, but don’t forget to incentivize employees who help you service clients and meet firm goals.

Horizontal teams: Sharing responsibilities so advisors can focus on specialized services

A horizontally aligned team can be appropriate for a team that has specialized skills and wants to give each advisor more autonomy. This team structure features more than one advisor in a co-lead role, with each partner focusing on a particular set of services. For example, a firm could have three lead advisors focused on retirement planning, tax and estate planning and multigenerational planning, respectively.

Associate advisors and client service staff members with complementary skills can be attached to the corresponding lead advisor and interface with clients on more tactical needs, such as transferring money between accounts or filling out paperwork. Administrative staff would layer underneath the specialist groups to provide support. Lead advisors then have more time to focus on face-to-face client interaction, marketing and prospecting.

Almost 15 years after Ray Evans founded Pegasus Capital Management in Kansas City, Kansas, he had what would be a fortuitous conversation with two other advisors within the Commonwealth organization. “Man, wouldn't it be fun to get under the same roof and see if the synergy we think that would happen, actually happens?” he recalled.

A few years later in 2017, several Commonwealth advisors joined to form Infinitas Wealth Council, now a 21-advisor, 48-person wealth management firm featuring a team of specialists. The horizontally aligned team structure enables the organization to focus on specialized but complementary skill sets in serving clients. “One of the partners has a terrific practice with people who work for publicly traded companies, so he’s the incentive stock option specialist,” Evans says. “We had an advisor who’s got an expertise working with families that have special-needs family members.”

Infinitas shows how a horizontal team structure can enable advisory firms to leverage individual advisory expertise to serve a wider swath of clientele and offer a broader range of services to them. Generally, advisors leading horizontal teams are comfortable sharing decision-making and equity among the lead advisors to focus on passions, talents or specializations.

Horizontal teams provide advisors the support to offer specialized service

Source: Capital Group

Incentivizing horizontal teams

Keep in mind that horizontal teams can be more difficult to manage, especially when leaders disagree on a firm vision or goals. And sharing leadership could foster a “keeping score” mentality and potentially corrosive competition among the lead advisors when it comes to compensation and how best to run the firm.

Equally splitting revenues among partners might seem to be a tidy solution but could actually not be fair, depending on how the firm performs. An advisor with rainmaker tendencies might bring in more new business than a partner who focuses on the lower profile but arguably equally important work of running the firm. One partner might bring in a huge account, skewing the year’s revenue and assets under management toward her.

Managing this is a two-step process, Schweitzer says. First, each partner should have a clear understanding of how their role relates to the firm’s overall mission and priorities and how it connects to the growth of assets under management and revenues. Advisors who operate on horizontal teams should consider additional methods of measuring compensation that analyze each partner’s contribution in a given year.

Since market performance, as well as contributions from individual partners, can vary from year to year, using a three-year rolling average to determine compensation participation levels is one way to reduce this volatility and incentivize advisors to stay engaged in growing the business.

Schweitzer suggests hiring a coach to help facilitate what can be difficult conversations, even if the firm is currently successful. The idea is to scenario-play how the team will handle potential conflict. Well-intentioned people will disagree about the best direction of an advisory firm, the types of clients they should serve and how to structure compensation for themselves and their employees.

“To do this, the partners need to spend the time for a deep discussion to make sure everyone accepts this process, ideally before conflict has a chance to occur,” he adds.

Takeaway: Horizontal teams can allow advisors to specialize, but ensuring a partnership thrives requires creatively structuring compensation and ongoing open lines of communication among individuals to allow those formulas to change as needed.

Hybrid teams: Creating a hybrid team structure to support a holistic advisory services firm

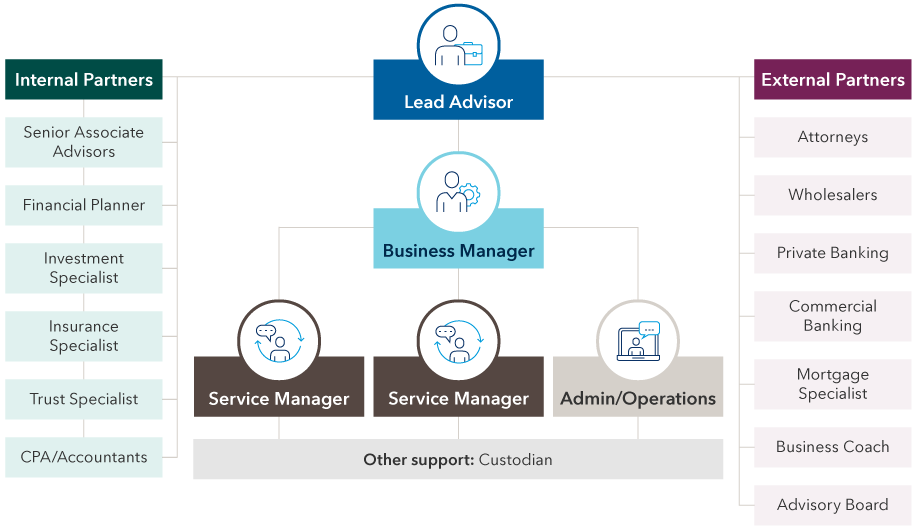

A hybrid team structure leverages aspects of both vertical and horizontal teams to try to create a holistic firm that can handle all client needs. Typically, these teams feature a financial advisor acting as a CEO who runs day-to-day operations. Senior associate advisors set the firm’s overall strategy with the CEO and run vertical teams composed of associate planners and specialists (such as those in insurance, investment or trust) to service clients according to those specialized needs.

External partners like a COI network and an advisory board often round out the greater team to connect clients to other services as required, such as private banking, business coaching or legal advice. An outside advisory board helps firm leaders gain insight into new markets or emerging client needs while also acting as an important source of client referrals.

As hybrid teams grow, advisors can further narrow the scope of the services they provide or the client profile they serve. “Advisors get better at what they do, their execution goes up and client satisfaction increases,” Schweitzer says.

Hybrid teams feature elements of both vertical and horizontal teams

Source: Capital Group

Incentivizing hybrid teams

For hybrid teams to work effectively, the advisor/CEO must realize she is not in a rainmaker role, which is a role more familiar to senior advisors. Instead, she should embrace a more internally focused remit that’s concerned with team communication and culture, creating codified processes for the client experience and regular post-mortems on both wins and misfires.

Hybrid team structures generally require a larger bureaucracy, including robust human resources and operational roles, to manage both internal team members as well as external partner relationships. “Historically, advisors haven’t spent a lot of time on these activities,” Schweitzer says. “But it’s critical to have a disciplined process around who does what and how, so if someone leaves the business or is absent for vacation or illness, another person can slide in without interrupting client service.”

Next, clients need to be educated that they will be working with a variety of members on a team, depending on the specific service needed. “Advisors tend to overpromise, saying ‘Call me with anything,’ but that’s not realistic,” Schweitzer says. “If, for example, a dividend check didn’t hit an account, they should know to call someone on your team or know how to access the firm’s online portal for those sorts of issues.”

Karen DeRose, founder and managing partner of DeRose Financial Planning Group in Chicago, leads a team of 10 consisting of advisors, paraplanners and marketing and support staff providing individual planning, business planning and investment management. It can take six months to onboard new clients, and she says they are “touched” at least 20 times during the first year.

Clients will become accustomed to interacting with a team of people, not just one advisor, DeRose says. “Everybody works on the client, meaning everybody knows everything about the client, who feel well taken care of,” she says.

Takeaway: Hybrid firms can enable you to offer a wide breadth of specialized services, but they require a robust firm infrastructure and a culture that has codified how clients receive services.

Michael Schweitzer

Michael Schweitzer