Financial Planning

Portfolio Construction

If you have received a large inheritance or worked at the same company for a number of years, there’s a chance that much of your wealth revolves around a single stock. This can be rewarding when shares of the company are rising, but it may expose you to significant risk if the price were to drop unexpectedly. Regardless of the size of a company or its past achievements, there is always the danger of a favored stock tumbling amid a business setback or broad market decline. To avoid potentially serious damage to your portfolio, it’s sometimes advisable to diversify out of such concentrated positions. By reducing overexposure to one stock, you may lower certain risks in your overall portfolio and leave yourself better positioned to achieve your long-range goals.

There is no single definition of “concentrated stock,” but a broad rule of thumb is that any position making up more than 10% of a portfolio should be reviewed for appropriateness. To be sure, not every concentrated position needs to be sold off. In fact, it may be possible to hold a sizable amount of one stock if your portfolio has a solid foundation of well-diversified investments to help meet your goals. But if a single holding makes up a sizable portion of your overall wealth, as is often the case, it’s generally best to consider diversifying.

Despite the risk that comes with concentrated positions, the natural instinct is to assume that a successful company will fare as well in the future as it has in the past. Even if a stock has fallen from its peak, investors can be convinced it will rebound. Academic studies show overconfidence is common, as investors tend to overestimate the upside while significantly downplaying the risks.

Single holdings add another layer of investment risk.

Broadly speaking, there are two fundamental types of risk with stock investing. The first is market-related: the threat of economic weakness causing the entire stock market to drop. All equity investors are subject to market risk and the sometimes bruising sell-offs that are inherent in stock investing. The second type of risk is specific to individual companies: the chance that adverse conditions in a business, such as the loss of a major client, could drive down its shares. This company-specific risk can be a bigger danger over the long term because while the broad market has historically bounced back from declines, many individual stocks have not.

Business-specific risk is especially pronounced among smaller companies, which tend to have limited financial wherewithal to ride out challenges. But a surprisingly large number of established blue chips also have been undercut by forces ranging from short-sighted management to shifting market trends to accounting scandals. Among the more prominent casualties: Lehman Brothers, WorldCom, Enron, Washington Mutual and Circuit City.

In fact, only 56% of the Fortune 500 in 2000 are still on the list today. The rest have either gone bankrupt, merged with another company or simply fallen from the ranking. By one estimate, a mere 12% of companies on the Fortune 500 in 1955 were still on the list 60 years later.

A rising market doesn’t mean every stock moves higher.

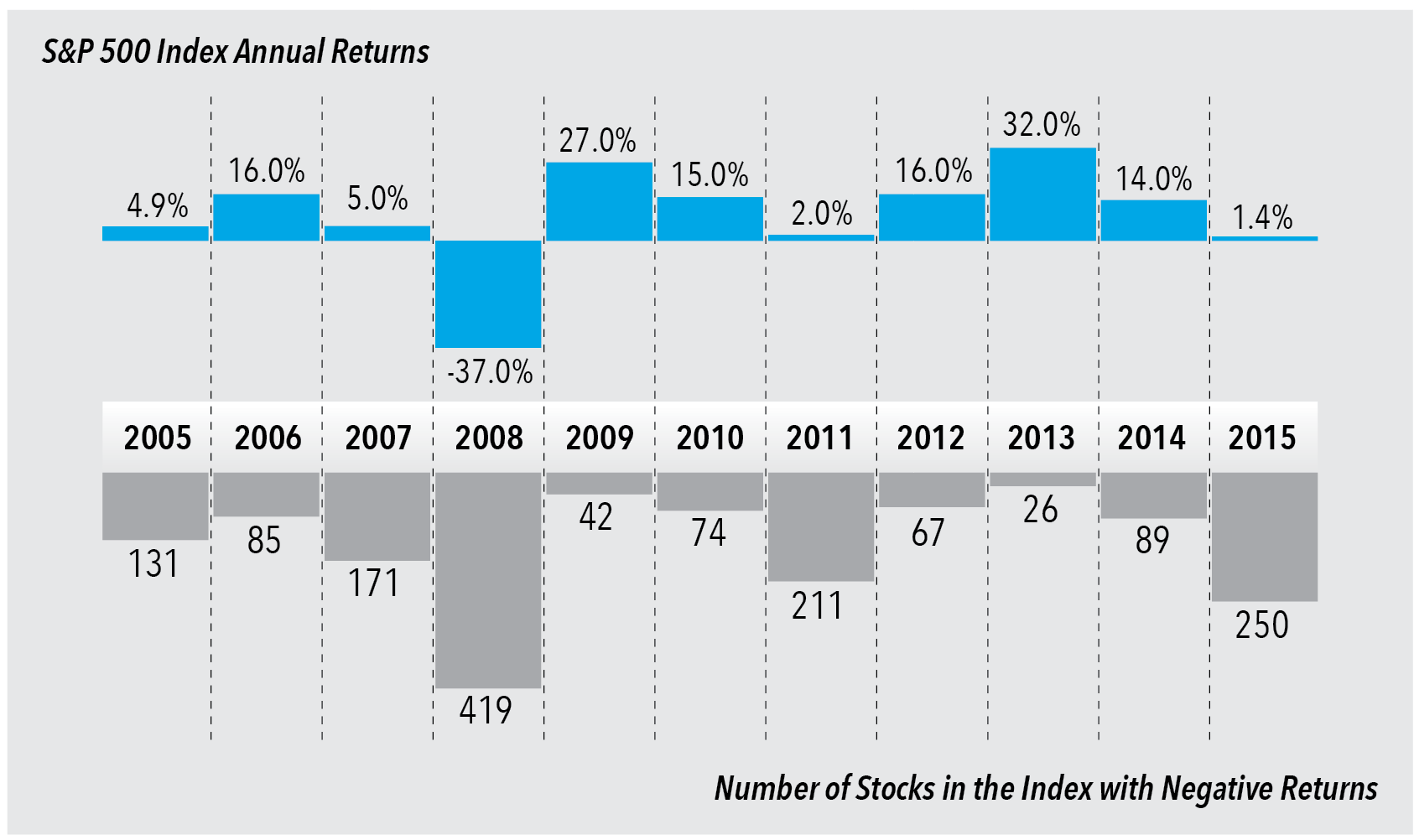

Over time, the S&P 500 has risen more often than it has fallen, advancing in 75% of rolling one-year periods since 1926. But as depicted in the chart on this page, even in years when the market itself is up, not every stock follows suit. In 2015, for example, the S&P 500 rose 1.4% but half the stocks in the index were down on the year. In 2014, the index climbed 14% but nearly one in five stocks fell.

Beyond that, volatility tends to be higher for individual stocks than for the market as a whole. The average stock in the S&P 500 is twice as volatile as the index itself. Not surprisingly, stocks of smaller companies tend to fluctuate more than those of larger ones. Volatility is important, in part, because it can affect the timing of a sale. An investor who wants, or needs, to sell during a downturn could experience a heightened loss if the timing is particularly unfortunate.

One of the biggest concerns about concentrated stock centers on taxes. There’s no doubt that an investor with a low-basis position in a stock held for many years could face a sizable tax bill when selling shares. However, the tax impact should always be put into context. The maximum long-term federal capital gains tax rate is currently 20%. Upper-income wage earners are subject to an additional 3.8% net investment income tax, although this tax is assessed only on the gain realized, not the entire value. Still, you should measure the total potential 23.8% tax hit against the possibility of a stock losing one-quarter or more of its value, which can be a very real possibility in a market sell-off.

Consider alternatives to outright selling.

Of course, there are instances when it may not be advisable to liquidate a concentrated position. For example, for clients in poor health or who are advanced in age, it may be more tax-efficient for their heirs to diversify after receiving a step-up in cost basis following the client’s death.

Likewise, investors can donate concentrated stock to charity instead of selling it. By donating stock, you may be able to avoid paying any embedded capital gains tax while benefiting from the tax deduction. Giving some shares to charity also can be done in conjunction with selling your position. By doing so, the charitable income tax deduction can help offset taxes from the sale of shares.

To determine how much of a concentrated holding may be appropriate in your specific situation, it’s helpful to view it through the lens of our Wealth Strategy Pyramid. We construct portfolios from the ground up, with a “base” made up of short-term funds that support near-term spending. Then we build the “core,” or the amount of money needed to endow your lifestyle. In calculating the core amount, we use conservative estimates that take into account the likelihood of occasionally poor markets and the possibility that you will live a long life. These assets are generally invested in a broadly diversified global mix of asset classes. Additional assets beyond the base and core are viewed as “surplus.” It’s within this surplus portion of your portfolio that you have flexibility to hold concentrated stock, because a significant loss, were it to occur, should not affect your lifestyle.

Each client’s situation is unique, and it’s important to analyze the range of options available. Examining the totality of your finances — including time horizon, risk tolerance, spending needs and financial goals — helps to position your portfolio so that it has a solid foundation that doesn’t turn on whether a concentrated position rises or falls. This process also serves to quantify how much of a concentrated position you can potentially afford to hold within the parameters of your long-term financial objectives.

A Rising Tide Doesn’t Lift All Boats

Even in years when the market itself rises, a significant number of stocks do not.

Source: Calculated by Capital Group Private Client Services using data from FactSet. Returns reflect the reinvestment of dividends, interest and other earnings for each annual period between January 1, 2005 and December 31, 2015. Stocks in the index with negative returns represent individual holdings in the index with returns less than 0.0% for the annual period.

Related Insights

Related Insights

-

Tax changes are almost certain. Are you prepared?

-

Tax & Estate Planning

When searching for the perfect trustee, consider a team -

Artificial Intelligence

For better or worse, AI fireworks propel the market