Equity

Artificial Intelligence

The S&P 500 is supposed to tell a simple story — how the average stock and, by extension, the heart of the equity market, are doing. And the index does that very well — except, of course, when it completely doesn’t.

On the surface, the S&P 500 has ridden a helium-pitched rally to a series of record highs. But looked at more closely, two-thirds of this year’s advance comes from an achingly small band of technology giants whose shares have been gassed by enthusiasm over artificial intelligence. AI darling Nvidia has contributed one-third of the gain all by itself.

This has created a split-personality market brimming with both risk and opportunity. The obvious downside would be unexpected bad news — disappointing earnings, an exogenous shock or an overly dilatory Federal Reserve — that weighs disproportionately on tech juggernauts with princely valuations. But the preoccupation with AI has also opened opportunities among a wide range of overlooked industries and companies with solid earnings and restrained valuations.

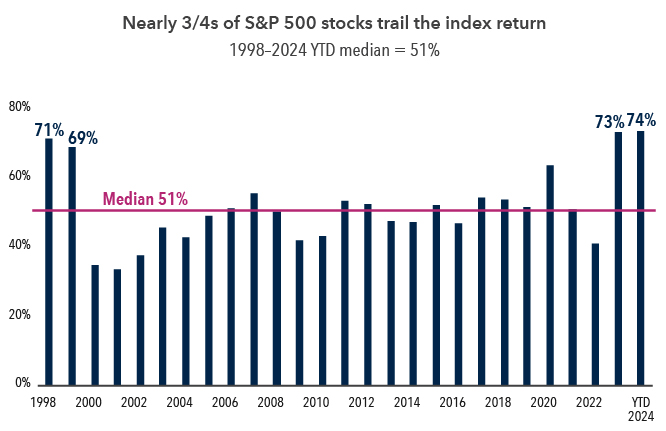

Looked at in historical terms, the domination of the so-called Magnificent Seven has produced an even greater level of tech concentration than occurred in the dot-com meltdown of the late 1990s. The S&P 500 has leapt more than 15% this year — but the median stock is up just 4% and was actually down in the second quarter. As a result, the top 10 stocks make up 37% of the S&P 500 market capitalization today compared to 27% at the tech-bubble peak.

The surge in tech megacaps has led to an abnormally top-heavy market

Source: LSEG Refinitiv, S&P 500. The indexes are unmanaged and, therefore, have no expenses. Investors cannot invest directly in an index. Past results are not predictive of results in future periods. As of June 30, 2024.

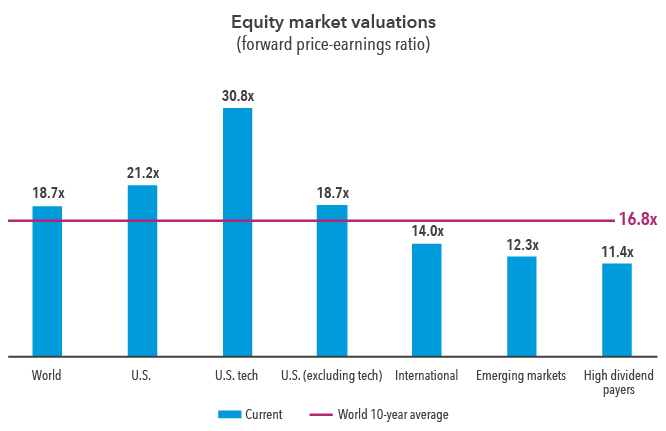

Make no mistake: There’s a big difference between now and then. Today’s megacaps have formidable earnings and proven business models. The key question, however, is whether their AI potential and future earnings merit valuations of Brobdingnagian proportions. The sector trades at roughly 31 times earnings, which is swollen even by its normally lofty standards.

Despite strong fundamentals, the market capitalizations of the top five tech stocks have far outpaced the companies’ underlying profits. This suggests that investors have already priced in best-case growth scenarios. Additionally, the profit lead of the five megacaps over the rest of the index is projected to narrow.

By comparison, every other sector sports a far more reasonable valuation, landing at or near its 10-year averages. The outsize level of tech concentration is not expected to continue, potentially opening a window to other sectors and markets. Some even stand to benefit from a potential AI spillover effect, including electric utilities and consulting firms.

Equities around the world appear to be reasonably valued — with the exception of U.S. tech giants

Sources: LSEG, MSCI, S&P Dow Jones Indices. A price-earnings ratio, or P/E ratio, is a measure of a stock's relative value and calculated by dividing a company's stock price by its earnings per share. Forward P/E ratios are based on estimates of earnings over the next 12 months. World 10-year average forward P/E ratio is the average forward 12-month P/E ratio of the MSCI World Index. World is represented by MSCI World Index; U.S. by S&P 500; U.S. tech by S&P GICS tech sector; U.S. (excluding tech) by S&P 500 less the S&P GICS tech sector; International by MSCI EAFE Index; Emerging markets by MSCI Emerging Markets Index; and High dividend payers by the top 1/3 of stocks with highest yields in the MSCI World Index. Investors cannot invest directly in an index. Data of World 10-year average from June 30, 2014, through June 30, 2024. As of June 30, 2024.

A soft landing in the U.S. appears to be feasible.

Underlying conditions remain extremely favorable, with a hoped-for soft landing increasingly within reach. Inflation has continued to retreat, GDP growth has been sturdy, productivity has perked up and earnings expectations have risen for this year and next. Meanwhile, this exceptionally long period of low unemployment continues to produce handsome consumer spending. Overall, the U.S. economy remains a standout compared to most other wealthy nations.

Though the timing of anticipated Federal Reserve rate hikes has been pushed back repeatedly, the central bank is widely expected to begin loosening this year, perhaps as early as September. Having made headway against inflation, other global central banks have already swung into action. In June, the European Central Bank cut rates for the first time since 2019, a notable move that could telegraph the gradual start of a global rate-cutting cycle. The Bank of England is expected to cut at its next meeting.

To be sure, there is still a possibility of recession. Despite its modest level, unemployment has picked up. Leading economic indicators remain down. There’s pressure on commercial real estate, as well as a rise in credit card balances and delinquencies. Recessions can happen suddenly, often in response to some sort of unpredictable shock.

The election remains a political question mark.

As detailed in this space previously, the financial markets have generally done well over the long term regardless of who occupied the Oval Office and which party controlled Congress. Still, the unsettled presidential election underscores the clashing and sometimes contradictory ways that Americans perceive the economy.

High-income consumers have spent freely thanks to the convergence of several factors. Homeowners with low-rate mortgages from years ago are insulated from today's higher rates. The scorching U.S. dollar has sparked a frenzy of global travel. And rising stock prices and home values have made people more willing to open their wallets.

But as discussed in this story, many voters see a bifurcated economy. Though headline inflation has softened, price tags are still dramatically higher than they were a few years ago. On average, prices are up 24% in a little more than five years. The eye-watering costs of buying a first home, paying off student loans and affording child care have left a visceral feeling of uneasiness among many voters that has turned the economy into an unexpected wild card this election season.

Similar chasms have played a part in elections elsewhere, including in France and Britain, which both face societal distress and political fallout. Nevertheless, from an investment standpoint, those forces are unlikely to have much impact on businesses based in those countries that sell the bulk of their goods internationally.

Bonds are unusually attractive.

After a self-assured rally in 2023, fixed income has backpedaled slightly this year as Fed rate cuts have been delayed and their expected scope has been narrowed. Nevertheless, bonds appear to be especially compelling vis-à-vis stocks and cash.

As is normal, equities are likely to have greater absolute returns than bonds over the long term. However, a financial measure that gauges their comparative appeal on a risk-adjusted basis significantly favors fixed income. In fact, the comparative appeal of bonds is at a 20-year high.

Fixed income is also attractive relative to cash. Given that rate cuts are projected later this year and into 2025, investors can lock in today’s higher rates while potentially getting a pricing bump if yields fall. By comparison, cash yields would drop as the Fed lowers rates.