Artificial Intelligence

India

A few weeks ago, the energy that had been powering India’s booming economy and stock market seemed to pause for a brief moment.

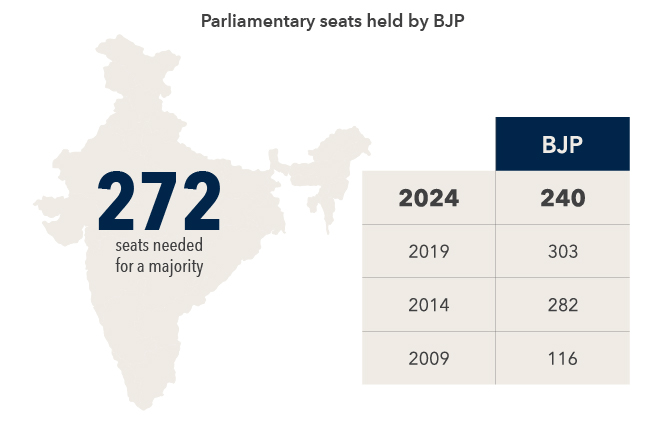

In national elections, Narendra Modi secured a third consecutive term as prime minister — a historic feat accomplished only once before in the 77-year-old republic. But the achievement was overshadowed by a poor showing in Parliament by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), which lost 63 seats compared to 2019. That not only stripped the BJP of its parliamentary majority, but it was a far cry from the legacy-defining landslide that had been forecast.

More important, Modi himself had pitched the vote as a de facto referendum on his vision and leadership. It‘s a setback, especially on the heels of emphatic wins in state elections in November and December 2023. The most immediate impact came in the stock market, which sold off on fear that Modi might have to throttle back long-running economic reforms.

However, I believe the jitters were greatly overdone and that the outlook for India — which is both the world’s most populous country and the fastest growing major economy — remains bright.

Many of the forces that have paced India’s growth in recent years are firmly in place. Those include its solid recovery from the pandemic, youthful demographics and position as a geopolitical fulcrum amid fractious relations between the U.S. and China.

Even the electoral setback is minor and not altogether unwelcome. The BJP has retained all key ministries and the ministers themselves remain unchanged from the previous cabinet, indicating continuity and Modi being firmly in control of the government. Still, the opposition parties are considerably strengthened, and the new government will not find it easy to push through its decisions in Parliament without brooking any opposition. A more accommodative Modi could become a long-run positive for the country.

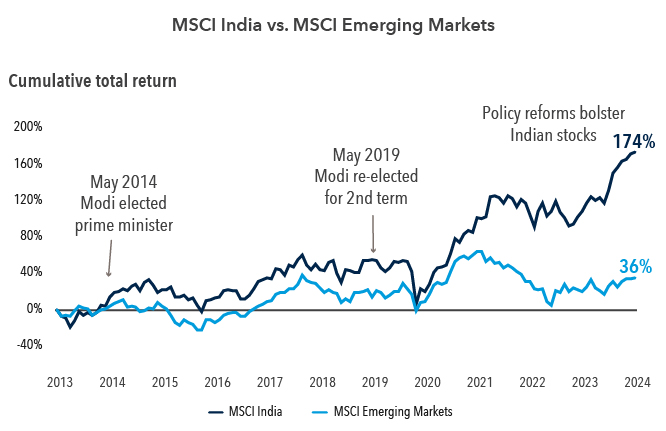

Indian stocks have surged during Modi's tenure

Source: MSCI, RIMES. Data as of May 31, 2024.

To be sure, India faces stiff challenges. Near the top of the list are insufficient job creation, especially positions that pay decent wages, and a perceived increase in inequality. Despite robust GDP growth, the economy simply hasn’t produced enough good jobs, especially for educated young people seeking to escape the menial labor that is prevalent outside major cities. While it is tempting to identify a cause for the election results, voter preferences are usually more complex and an interplay of local and national issues. However, various surveys and polls have shown that the lack of jobs and inflationary pressures were key concerns of the electorate.

Nevertheless, India has made enormous strides across a range of social and economic metrics that I expect will continue apace. The government has undertaken key fiscal reforms, devoted resources to badly needed infrastructure improvements and introduced reforms to make the business climate more welcoming to the private sector, for both Indian companies and multinationals. Currently the world’s fifth-largest economy, India has ambitions of moving up to third in coming years, behind only the U.S. and China.

Put all of this together and I view India’s economy as being in a sweet spot — an oasis of relative calm and steady growth in a turbulent world.

The election was a surprise but the growth story is intact.

The voting results were a disappointment for Modi. The BJP won 240 seats in the country’s 543-member Parliament, falling short of the 300-plus that were expected and the 272 needed for a majority. That trailed the 282 seats the BJP captured in 2014 and the 303 seats it took in 2019. For the first time in Modi’s decade-long tenure, the BJP has to depend on other parties in a coalition government.

India sees first coalition government in a decade

Sources: Capital Group, media reports. Data as of June 2024.

That may make it difficult to push through some unpopular but necessary policy and reform measures. The privatization of banks will likely be one early casualty. Hopes for land, agriculture and labor reforms are likely to be ratcheted back, although their prospects were always shaky given previously failed attempts. Given that many of these subjects also fall under the domain of the states, the reforms would likely be driven at the state level as they compete for investments and job creation.

Nevertheless, it’s still impressive that the BJP secured a comfortable majority after a 10-year run of power, especially considering the inevitable effect of voter fatigue. Barring unexpected snags, a coalition government should be workable given that BJP at its core is not very far from simple majority and is critically dependent on only two coalition partners. It was India’s modus operandi from 1989 until 2014, when Modi became prime minister and the present coalition government is likely to be stable given the BJP's strength. The important consideration from the perspective of the economy and markets is that under various coalition governments, the economy, reform efforts and financial markets have done reasonably well and there has never been a reversal of any major reforms or policy.

Indeed, stocks rebounded quickly from the initial electoral shock on the belief that India’s economic progress will continue. The market, which has been on a sparkling run the past several years, rallied to fresh highs days after the vote.

Infrastructure development is likely to continue.

Modi was elected in 2014 on a pledge to torque the economy, reduce bureaucracy and extirpate the entrenched corruption that had matted down progress for decades. He’s made progress on all of them.

His administration has focused heavily on infrastructure development to propel economic growth. Money has poured into roads, bridges, airports and clean energy, among other things. That’s helped to support manufacturing, improve supply chain efficiency and foster a crop of digital start-ups. There has also been steady progress in the business environment, including clear gains in stanching corruption and extending digitization across society. Various policy measures and regulations have helped usher in a healthy banking system, deliver social benefits to the marginalized in society without large leakages, boost manufacturing and strengthen the operating environment in various sectors such as real estate.

I don’t foresee major changes to the core economic focus of the last government — a push for higher infrastructure investment, growth in manufacturing and a focus on renewable energy and energy transition. Policy support for key domestic industries such as defense, space, semiconductors and energy are likely to continue, as well as heightened attention for technology and digital public infrastructure.

Compared to other major economies, the ill effects of the pandemic were muted in India due to targeted intervention and support to segments of the economy that needed it at that juncture. The government went into the COVID downturn in decent financial shape and didn’t undertake excessive fiscal spending to prop up its economy. That suppressed inflationary pressures and helped avoid the runaway price hikes that struck some other nations.

The pandemic also fostered a greater willingness to offshore work to India. The work-from-home trend, in which digital nomads spread out across the U.S., convinced businesses that they could outsource work beyond U.S. shores. Notably, the nature of work being offshored to India has broadened. The nation still attracts plenty of call-center-type operations. But it’s luring more high-end and specialized work, such as legal services that U.S. businesses were once reluctant to entrust to India.

India can benefit from China’s challenges.

India is well positioned to take advantage of the current headwinds besetting China, including its economic downturn, real estate upheaval and geopolitical clash with the U.S. Neither India nor any other country can supplant China’s vast manufacturing apparatus. But India stands to gain from “China plus one” — the reimagining of supply chains in which businesses are reducing their incremental exposure to China by setting up or expanding secondary outposts. Mexico and Vietnam are likely to be the biggest beneficiaries, but India has notched some big wins. For example, Apple has significantly increased iPhone production in India, a vote of confidence that I believe will coax other businesses to follow suit.

The U.S. and China are locked in a race for primacy in areas such as artificial intelligence and advanced semiconductors. India is unlikely to attract such next-generation technology work. But India is well positioned to lure a variety of mid-range operations — for example, churning out chips for the auto industry — that would mark a clear step up for the country and that is where India’s well-conceived policy focus is.

On the whole, I expect India’s growth will come from these dual prongs — mid-range manufacturing on one end and higher-value services on the other.

India must overcome lingering problems.

Unlike most other major economies, India has a youthful population, with roughly half of its citizens estimated to be under the age of 25. That so-called demographic dividend exempts India from the shrinking workforces and attendant costs of elder care bedeviling other societies.

However, India has struggled to produce enough good-paying jobs for this increasingly educated cohort. This has prevented the movement of a large cross-section of rural youth from agriculture to more productive parts of the economy. That’s shown in the intense competition among young people for coveted government jobs, which are increasingly fewer in number. Far from setting out on ambitious careers that could propel collective economic growth, scores of freshly minted college graduates clamor for a fractionally small number of stable government positions that open each year. Eventually, most have to settle for lesser jobs, often returning to the impoverished rural communities they had sought to flee.

That dynamic is exacerbated by a push toward factory automation and the advent of artificial intelligence. Manufacturers are prioritizing robots over humans in the pursuit of operational efficiency. However, that deprives a generation of workers of a key steppingstone that has historically helped the poor transition into the middle class.

Despite the challenges, India has made vast strides in economic growth that have translated into improving conditions for its citizens. I expect these dynamics to continue and believe that the long-term outlook for India is quite positive.

Related Insights

Related Insights

-

For better or worse, AI fireworks propel the market

-

Equity

Q&A with Greg Miliotes -

Long-Term Investing

Celebrating five decades of serving you

Anirudha Dutta

Anirudha Dutta