Artificial Intelligence

Election

Consumers are dispirited even as the economy powers ahead. Are they just fickle, or do they know something that official statistics don't show?

“Are you better off than you were four years ago?”

With that one blistering question, Ronald Reagan cemented his lead against Jimmy Carter in the 1980 presidential election, underlining the pain that bounding prices, oil shortages and surging unemployment had inflicted on voters. A few cycles later, Bill Clinton would unseat George H.W. Bush after adopting a slogan from an acidic internal campaign memo: “It’s the economy, stupid.”

Economic health is one of the most perpetually salient flashpoints in modern U.S. politics. It’s easy to see why — foreign engagements and dense policy are important but somewhat remote from most people’s day-to-day experience. Conversely, high unemployment, elevated inflation and stagnant wages have tangible and immediate impacts.

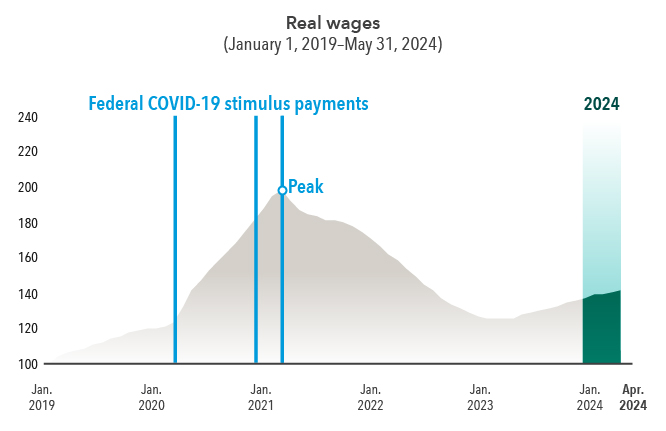

Real wages have risen in 2024, but are still down from their stimulus-powered 2021 peak

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Capital Group. Real wages are indexed to 100 on January 1, 2019, and reflect the effects of inflation on consumer purchasing power. As of June 30, 2024.

Fairly or unfairly, that feeds through to elections. Though widespread concern about his age was the primary factor behind President Joe Biden’s decision to drop his re-election bid, dissatisfaction with the economy — and particularly with inflation — had clearly weighed on his job-performance ratings.

The irony is that the on-paper performance of the economy would theoretically favor an incumbent. The U.S. economy has defied expectations of a recession, with GDP growing an enviable 3.2% in 2023. Unemployment has been uncommonly good. The inflation rate is trending down, a feather in the cap of the Federal Reserve and chairman Jerome Powell. Wage growth has been strong, with average real income — a measure that accounts for inflation — up over the last year.

“If you put me on a desert island and you told me these are the numbers, I’d think this wasn’t a bad economy. In fact, I’d think it was a pretty good result,” says Capital Group economist Jared Franz.

Yet many voters aren’t happy. The University of Michigan Survey of Consumers — a commonly cited bellwether — fell precipitously in 2020 and hasn’t recovered, with readings trending down again since March. There are some concrete reasons for the discontent: Though the inflation rate is easing, prices aren’t actually falling; they’re just growing more slowly. And though average real wages may be up versus 12 months ago, they’re still down from 2020. Housing affordability is down, too, in no small part due to the higher interest rates that the Fed is using to clamp down on price growth.

“The Fed and the market are focused on the rate of inflation, but consumers see that their hamburger costs a lot more, up to 50% more in some cases,” Franz says. “That’s what people feel, it’s what they see and it’s what they talk about at the dinner table.”

Sour sentiment could prove more powerful than the official data, making the economy a distinct wild card in this year’s elections. And given the Democratic and Republican parties hold starkly different views of governance and economic policy, today’s consumer mood could have yearslong ripple effects.

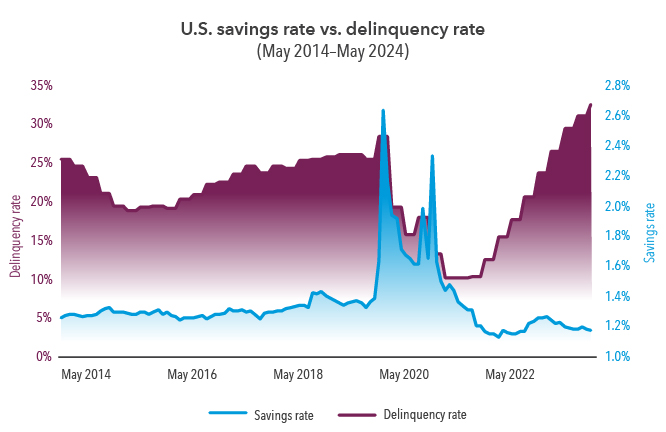

Economic data highlight reasons for optimism and caution

Sources: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Statista. The savings rate is represented by personal saving rate, calculated by the St. Louis Fed, as the ratio between personal saving to disposable personal income. Delinquency rate records the percentage of all consumer loans at commercial banks in the U.S. that were delinquent. As of June 30, 2024.

Consumers largely hate this economy despite its strengths — but that’s not necessarily a contradiction.

One of the weaknesses of economic snapshots is they don’t provide much context. This environment is a perfect example. Year-over-year figures mostly point in the right direction, with GDP growth projected to hit 2.7% this year, buoyed by strong consumer spending. U.S. inflation has been tamped to 3% in June — still above the Fed’s 2% goal but far more digestible than its 9.1% peak.

In the same vein, workers seem to be big winners. Labor markets remain tight. Unemployment hovered at or under 4% for more than two and a half years, finally snapping the run with June’s 4.1% figure, the longest such stretch going back to the ’60s. Wages have reflected that demand, steadily ticking up by 1% or more in 10 of the past 11 quarters.

Yet those figures elide how inflation has eaten into those salary bumps. Measures of real wages, which track the actual buying power of consumers rather than the dollar amount they’re taking home, have given up most of their gains since peaking in 2020. And what a peak it was: That April, real wages jumped 8.9% from a year earlier, largely on the back of the government’s pandemic stimulus. To put it in context, that’s nearly the amount that real wages grew in the two decades ending January 1, 2020. In an average 12-month period since 1979, real wages typically only grew 0.21%.

That spike has cast a long shadow over workers’ more recent gains. Real wages are higher than they were in 2019, but they’re just not as plush as they were in 2020. Consequently, many workers don’t feel as though they’ve made strides toward a more prosperous future. Rather, “many consumers see it almost as if they’re making up for decades of being underpaid,” Franz explains.

The issue is compounded for some subsets of workers. The tide of the tight labor market did indeed raise all boats, as the saying goes, but certain high-demand professions — such as nurses and construction workers — received the lion’s share of the benefits. Additionally, higher wages didn’t always translate into larger paychecks. For example, in California, where the hourly minimum wage for fast food is now $20, many companies responded by cutting hours.

“Jobs that had big supply-demand imbalances received astonishingly high wage increases, sometimes higher than they’ve ever had in the past,” Franz says. “But workers who weren’t in those industries didn’t necessarily get that benefit.”

The tension between the broader economy, consumer sentiment and how individuals are managing might be showing up in the data. The U.S. personal savings rate tumbled below historical averages in recent years, which is usually a sign that workers aren’t too concerned about near-term economic volatility. However, delinquencies are creeping upward, typically a red flag that consumers are struggling to make ends meet.

Sticker shock can have an outsize effect on consumer spirits.

There could be another reason why consumers are so dissatisfied with the state of affairs: Sticker shock can have an outsize effect on consumer spirits.

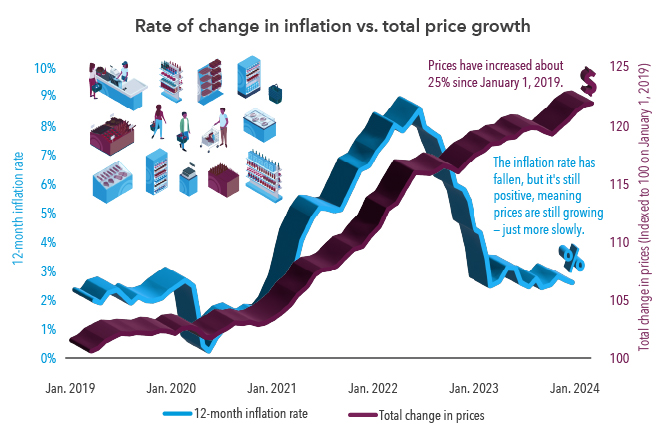

There's no doubt that prices are much higher now than they were before the pandemic, with the Consumer Price Index showing that costs have risen about 25% since the start of 2019. On big or recurring outlays, such as monthly food bills, car repairs or something as elemental as rent, it’s going to stick out, even if wages have kept up.

The sticker shock from higher prices could parallel loss aversion, one of the better researched facets of investor psychology. Most people are much more driven to avoid losses than they are to realize gains, a quirk that can lead even thoughtful investors to act in ways that might not align with their goals.

Recently, Neel Kashkari, the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, said he’s hearing stories to that effect from labor leaders.

“The American people ... really hate high inflation,” he said, adding that one of the leaders he spoke to flatly said recessions were less painful. Her reasoning was that when a person loses a job, they can lean on friends and family. But when inflation is high, everyone is sharing that pain.

Add to that the seeming disconnect between stubbornly high prices and repeated assertions from leaders and economic reports that the inflation rate has fallen, and you have a recipe for frustration.

“I think that’s part of what bothers people,” Franz adds.

“The level of inflation is much higher, and it’s not coming down. Keeping the rate of growth low — the goal of the Fed and other central banks — doesn’t do anything to resolve that underlying problem that consumers feel day-to-day.”

Economic sentiment could have ripple effects beyond the outcome of the presidential election.

While the rate of inflation has slowed, prices have not fallen

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Inflation is represented by the Consumer Price Index, which tracks changes in prices paid by urban consumers. Rate of inflation compares prices each month to prices a year ago, while total change in prices keeps a tally of how prices have changed since the index date of January 1, 2019. Total change is indexed to 100 on January 1, 2019. As of June 30, 2024.

In an election that has been marked by divisive topics, polls have repeatedly shown that inflation and the state of the economy are the top concerns for registered voters. In the immediate aftermath of Biden’s withdrawal, Vice President Kamala Harris emerged as the most likely candidate to head the Democratic ticket. As this issue of Quarterly Insights went to press, Harris appeared to be on track to sew up a majority of delegates to the Democratic convention. Of course, in a campaign season teeming with unexpected developments, it’s possible that the contours of the race could shift appreciably between now and Election Day.

As for the policies of the Democratic and Republican campaigns, both have been careful to signal that they have plans to respond to inflation — and to blame each other for elevated prices. The White House has often cited the large tax cuts created by 2017’s Tax Cuts and Jobs Act as a key cause, while former President Donald Trump has blamed Biden’s massive infrastructure laws and faulted the Fed’s response. Franz says there’s some truth to each of those accusations.

“The unfunded fiscal spending that ignited U.S. inflation in the first place started with Trump,” he explains. “However, fiscal largesse was extended under Biden with his spending acts — for example, The Inflation Reduction Act and the CHIPS Act. And the Fed tightened policy too late."

Regardless of the ultimate causes, the two camps have staked out starkly different approaches to tackling inflation.

Trump’s most direct action would be to potentially curtail the Fed’s independence, a significant change to longstanding policy designed to insulate the central bank from political consequences. He’s said he would remove the central bank’s chairman, Jerome Powell, who he believes has been too strict on interest rates.

Trump has also said he’d pursue aggressive oil and gas exploration and expansive tariffs to defend U.S. industries. Members of his campaign have also discussed weakening the dollar to spur exports. Most economists agree these would generally be inflationary — though higher oil and gas supply and lower interest rates could reduce energy costs and mortgages, respectively — but Trump may be aiming for higher growth to outpace their effects on price.

In the initial days of her campaign, Harris had yet to detail specific economic policies, but Biden's run may offer clues to her outlook. While on the campaign trail, Biden unveiled a tax program that would attempt to narrow the federal deficit, targeting primarily corporations and the very wealthy. He also said he would attempt to lower specific housing and health care costs through targeted homebuilding and drug-pricing programs, and pointed to his renewable-energy programs as important pieces in keeping overall energy costs down.

The White House has not said anything specific about the Fed, but thus far has maintained the traditional hands-off approach of previous presidents.

Related Insights

Related Insights

-

For better or worse, AI fireworks propel the market

-

Equity

Q&A with Greg Miliotes -

India

Despite election surprise, prospects remain strong for India’s economy

Jared Franz

Jared Franz