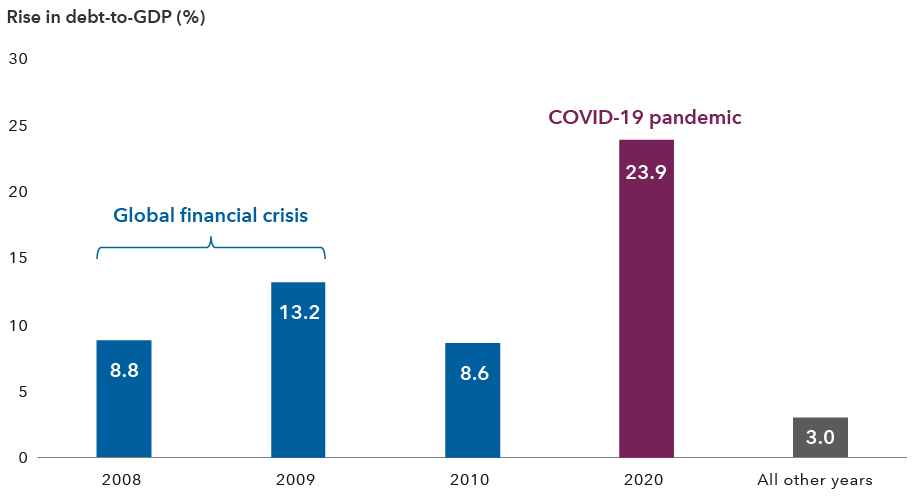

Fiscal risks aren’t always overblown, nor is the room to run deficits endless. Term premia (the additional return investors expect for holding longer dated instruments) is currently quite low and has been low for a long time. A sudden loss of appetite for Treasuries could indeed lead to a spike in term premia, but this is more likely to be driven by macroeconomic changes rather than debt sustainability fears. Previous episodes of term premium spikes, such as those in the 1970s and briefly following the COVID-19 pandemic, have centered more on inflation risk.

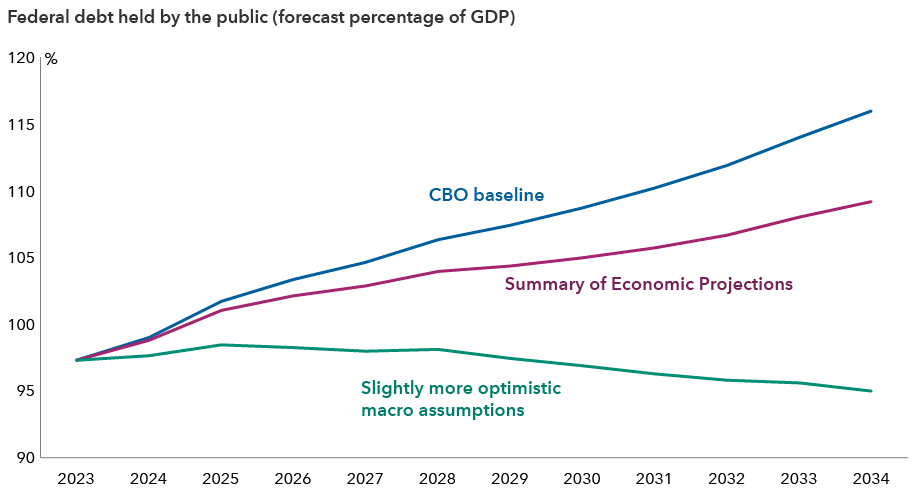

Term premia may rise, but U.S. Treasuries are likely to continue being priced as a rates instrument rather than a credit instrument, even if the debt-to-GDP ratio rises modestly. At these high debt levels, a sudden increase in term premia could significantly impact debt service costs, adding to the fiscal burden.

Furthermore, about 20% of U.S. debt, $7.16 trillion as of September 30, 2024, is intragovernmental debt, which has fewer economic consequences than debt owed to other investors, who may require higher interest rates in the future.

Does that mean that there’s no need to worry? Not exactly. The overwhelming majority of economists agree that deficits are currently too high, and the government will need to reduce them at some point.

A further rise in deficits from current levels that is not accompanied by economic growth or inflation would lead to a deterioration in so-called “r-g” dynamics, which can quickly escalate at high debt levels. (The r-g concept compares the real interest rate, r, to the real economic growth rate, g. Debt is more manageable if growth outpaces borrowing costs, but problematic in the inverse.) Another real worry is a loss of faith in institutions or concerns that policy action will not be timely or adequate.

While these scenarios should not be ruled out, for now, they are lower probability events, and in the absence of additional unexpected shocks, term premium levels are likely to remain low or see a moderate rise.