Brexit

- New trade barriers are likely to weigh on economic growth for years

- Deal could prompt a rebalancing of the U.K. economy

- Domestically focused U.K. stocks may be most vulnerable

Four and a half years after British voters narrowly backed a departure from the European Union, the two sides reached a trade agreement just days before the U.K.’s withdrawal from the EU’s single market and customs union on December 31. The deal avoids punishing tariffs and quotas on goods, but it still represents a significant rupture in the U.K-EU economic relationship.

One of the most immediate effects will be new trade friction as border checks and customs declarations are introduced on January 1. The U.K. has said it will phase in border checks over the first six months of 2021, while the EU plans to impose full checks in January. These hurdles will cost U.K. companies an estimated £7 billion ($9.4 billion) a year. In the short term, the U.K. may struggle to avoid logjams at key border crossings, while many businesses remain unprepared for the red tape.

This friction could depress U.K.-EU trade by around a third and reduce U.K. gross domestic product by about 5% to 7% over 10 to 15 years, relative to what it would have been had the country remained in the European Union, according to U.K. government estimates. The EU also faces an economic hit, especially in countries with deep trade ties to the U.K. Ireland, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, the Netherlands and Denmark are all likely to see a negative impact on their trade with the U.K.

Deal will increase regulation

The free trade agreement is one of the most extensive that the EU has signed with a major trading partner. It avoids tariffs and quotas for all goods and aims to limit the regulatory burden in some key sectors, such as chemicals.

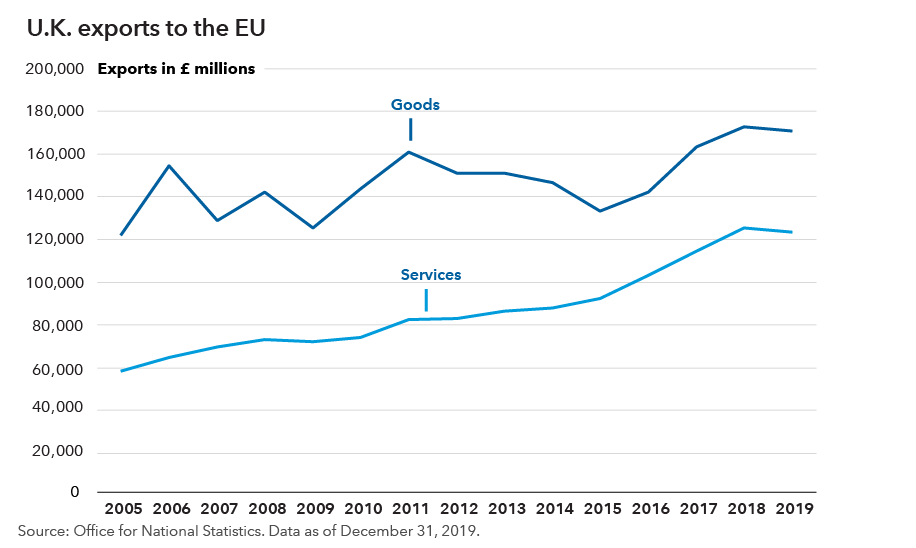

Still, the U.K. will face significantly higher regulation overall. Goods will be subject to rules of origin, which specify the extent to which inputs from another country can be embedded in U.K. products exported to the EU. This will be particularly important for cars and manufactured food and beverages.

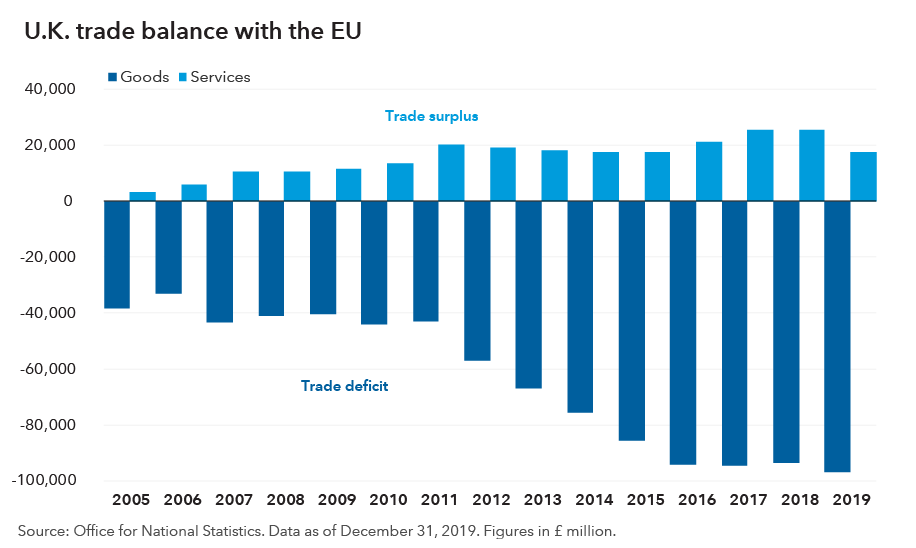

The agreement only partially covers services, such as transportation, with little regarding financial and professional services. The EU has said it will consider equivalence for these sectors, which would allow more access to the single market. However, this is much less favorable than “passporting” rights, which allow financial services companies with regulatory authorization in one EU country to conduct business freely throughout the bloc.

U.K. enjoys a trade surplus in services

After Brexit, a chance to rebalance the U.K. economy

The U.K.’s departure from the EU could lead to a longer term restructuring and rebalancing of the U.K. economy, with less reliance on the financial sector, housing and consumer spending. The government is anxious to start its “levelling up” agenda by developing the industrial north. That, along with new investments in technology, pharmaceutical research and environmental remediation, could help offset the impact of Brexit. However, the government’s deteriorating fiscal position may compromise its ability to support this rebalancing. Britain is already running a large budget deficit as a result of the coronavirus pandemic, and the economy is likely to need more support as it adjusts to the new trade relationship with the EU. The government’s debt-to-GDP ratio may rise sharply over the next five to 10 years as the economy adapts to a lower growth rate.

Over time, the U.K. could benefit from deeper ties with its global trading partners including China, India and the U.S., reducing its reliance on EU trade. However, countries that are geographically close and of similar income levels tend to trade more with each other. For instance, the U.K. currently conducts about three times the amount of trade with the Republic of Ireland, an island nation of about 5 million people, as it does with India, a nation of 1.4 billion that was once part of the British Empire. Any increase in U.K. trade with countries outside the EU is likely to be modest in comparison with the loss of trade with the EU.

U.K. stocks and currency may see short-term strength

The agreement should be a short-term positive for the British pound sterling and domestically exposed U.K. stocks, while exerting upward pressure on bond yields. Over the longer term, however, slower economic growth and any rebalancing are likely to weigh on U.K. stocks. Although many of the largest U.K.-based public companies are multinationals with limited exposure to the domestic economy, companies that derive more of their revenue in the U.K., such as retailers, banks, homebuilders and utilities, and those with significant export markets in the EU, are likely to be more exposed.

At a sector level, agriculture and automotive manufacturing were among the most vulnerable to a no-deal Brexit. About three-quarters of the U.K.’s agricultural imports come from the EU. As a result, new tariffs would have imparted a significant shock to U.K. food prices, which the government wanted to avoid considering the economic distress already wrought by the coronavirus pandemic. Even with a deal, some food price inflation is expected owing to health certifications and other border costs that will affect imports of food, as well as agricultural inputs such as animal feed. That may benefit discount food retailers as price-sensitive consumers seek to manage their food expenditures.

In autos, the U.K. is an important assembly hub for companies including Nissan, Honda and BMW, which sell finished vehicles into the EU market. The U.K. sent 51% of its vehicle exports to the EU in 2019, while the EU accounted for 81% of vehicles imported by the U.K. A no-deal Brexit would have placed significant stress on these supply chains, potentially leading some companies to relocate U.K.-based operations to the EU. While the deal avoids that scenario, automakers will have to abide by rules of origin requirements to maintain tariff-free access to the EU market.

Goods trade outweighs services

Landmark deal marks the end of the beginning of Brexit talks

Political pragmatism always argued for a deal, allowing U.K. Prime Minister Boris Johnson to assert that he delivered on his promise to “get Brexit done.” Amid the backlash against the government’s handling of COVID-19, the last thing it needed was a hard landing on Brexit. This would have looked like a failure of government — a gift to the opposition Labour Party ahead of local elections next year and a boon for the Scottish National Party, which backs independence for Scotland.

That said, the Christmas Eve deal did not mark the end of the Brexit process, but rather a milestone in a perpetual negotiation of the bilateral relationship. The current Conservative government has suggested it will try to exploit the potential for divergence from EU rules, although this could cause more tension with the EU, which insisted on a “level playing field” and an appropriate governance structure to handle disputes. A future Labour government may try to improve upon market access to the bloc.

Either way, the U.K. and EU will continue to engage on issues that the deal left unaddressed, as well as disputes that are likely to emerge. The experience of other non-EU countries, such as Norway and Switzerland, suggests the relationship with the EU may remain challenging. Indeed, the deal sets up more than 30 new bilateral committees to manage the U.K.-EU relationship.

Future U.K. governments will continue to wrestle with the question that has dominated the country’s relationship with the EU for decades: How much sovereignty is it willing to trade for access to the European single market? That was not resolved by the latest agreement. Thus, we may be living with Brexit uncertainty and a fractious U.K.-EU relationship for years to come.

Our latest insights

-

-

Global Equities

-

International

-

-

Global Equities

Never miss an insight

The Capital Ideas newsletter delivers weekly insights straight to your inbox.

Robert Lind

Robert Lind