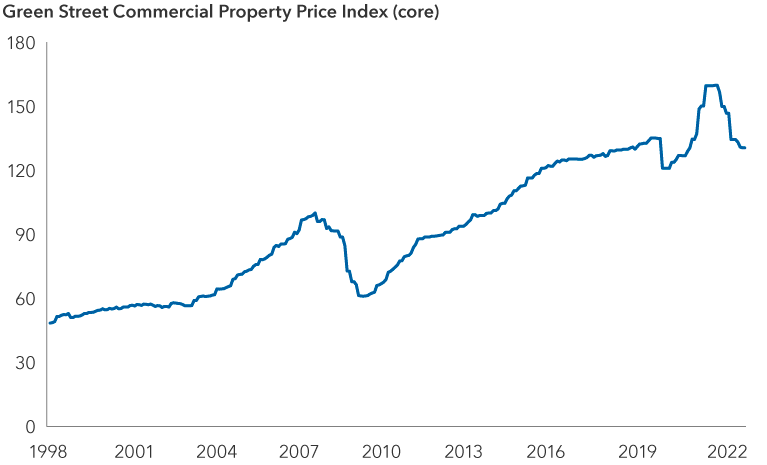

Is commercial real estate (CRE) the proverbial next shoe to drop for the beleaguered banking sector? Even before the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank, the outlook for parts of the CRE market appeared dim. Now with lending standards growing tighter, investors are getting increasingly nervous about problematic properties lurking on bank balance sheets.

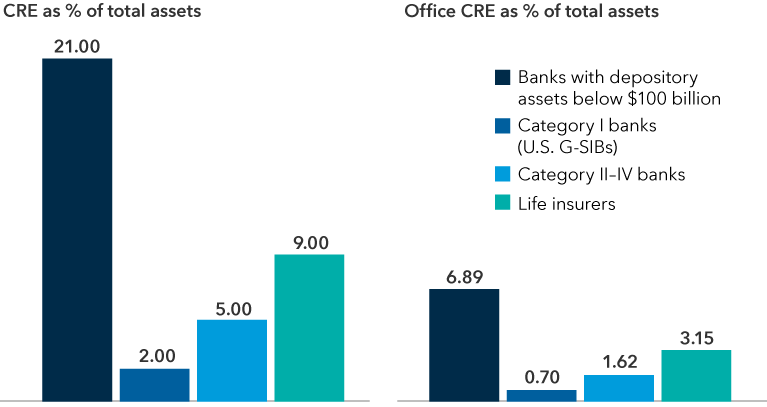

First, some context: Banks account for about half the lending in the approximately $5 trillion CRE loan market, mostly through fixed rate loans. The other half comprises commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS), lending from federal agencies such as Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, insurance companies, and to a lesser extent, mortgage real estate investment trusts (REITs).

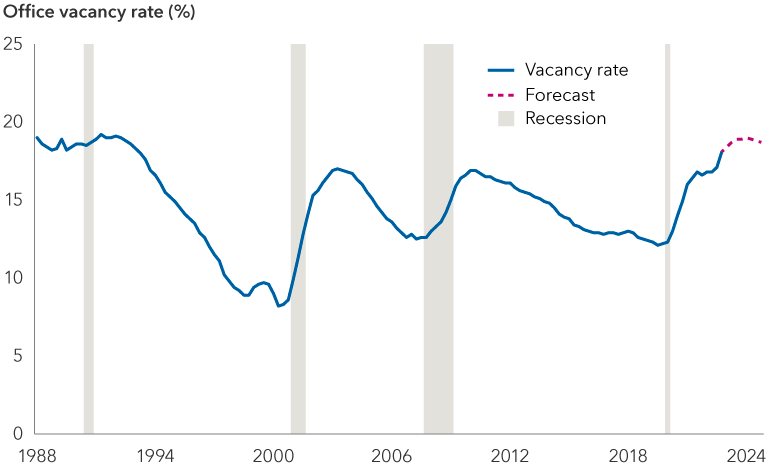

Overall, CRE is a heterogeneous market and cannot be painted with a broad brush. Office and retail properties look like the biggest concern, while other areas such as multifamily units and industrial warehouses could hold up relatively well.

On average, the debt maturities of CRE loans are laddered, or spread out, across 8 to 10 years, which mitigates potential risks typically associated with a surge in refinancing needs. Real estate borrowers who do have to refinance, or have high loan installments with falling property values, are likely to negotiate hard for lower payments or threaten to surrender properties — a tactic known as a strategic default.

The upshot is banks that hold significant portions of CRE loans on their books will likely see a hit to earnings. However, it appears unlikely these will trigger a banking insolvency crisis.

Meanwhile, most REITs seem relatively well positioned in this cycle, given their debt is generally well diversified and they have access to a broad set of lenders across banks and capital markets.