In observance of the Christmas Day federal holiday, the New York Stock Exchange and Capital Group’s U.S. offices will close early on Wednesday, December 24 and will be closed on Thursday, December 25. On December 24, the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) will close at 1 p.m. (ET) and our service centers will close at 2 p.m. (ET)

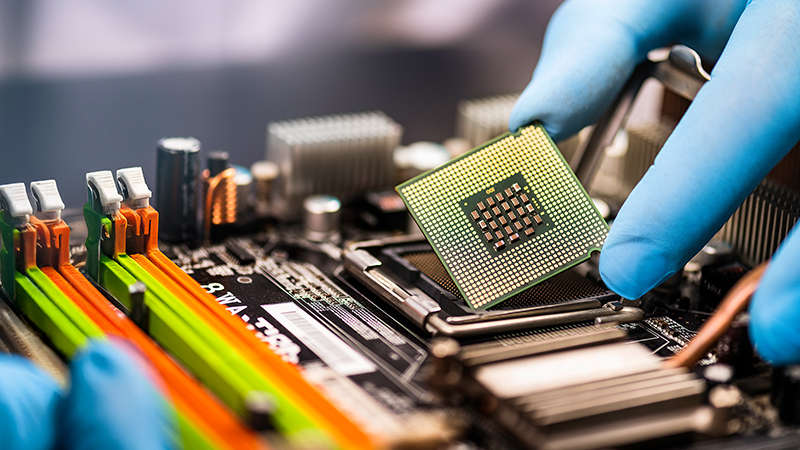

Powering AI: Energy crunch sparks investment surge

Made in America is making a comeback

What investors want for retirement

WHO WE ARE

Since 1931, we’ve been working with advisors like you to help achieve client goals

COURSES

Build and lead a high-performing advisory practice

An interactive course to help you lead with vision, scale with confidence and run a practice with clarity and purpose. Sign in for access.

Practice Management

How to talk with clients about AI

Clients anxious about AI and their portfolios, jobs or even how your practice is using it? Use this conversation guide.

Explore more investment and practice management insights

PORTFOLIO STRATEGIES & SOLUTIONS

Capital Group can help you and your business.

Portfolio Construction

See how our objective-based approach fits into your portfolio

RETIREMENT PLANS

Explore retirement plan solutions to help improve participant outcomes

FINRA’s BrokerCheck | Check the background of Capital Client Group, Inc., on FINRA’s BrokerCheck.