Economic Indicators

Market Volatility

- Stay calm and keep a long-term perspective.

- Maintain a balanced and broadly diversified portfolio.

- Balance equity portfolios with a mix of dividend-paying companies and growth stocks. (One tip: Don't overlook international equities.)

- Choose funds with a strong history of weathering market declines.

- Use high-quality bonds to offset equity volatility.

- For some investors, income protection in the form of variable annuities can be a good strategy.

- Financial advisors can help investors navigate periods of market volatility.

When is the next recession?

That’s one of the questions we hear most often. And for good reason. Recessions can be complicated, misunderstood and sometimes downright scary. With the U.S. expansion nearly 10 years old, investors may be wondering whether the next one is just around the corner.

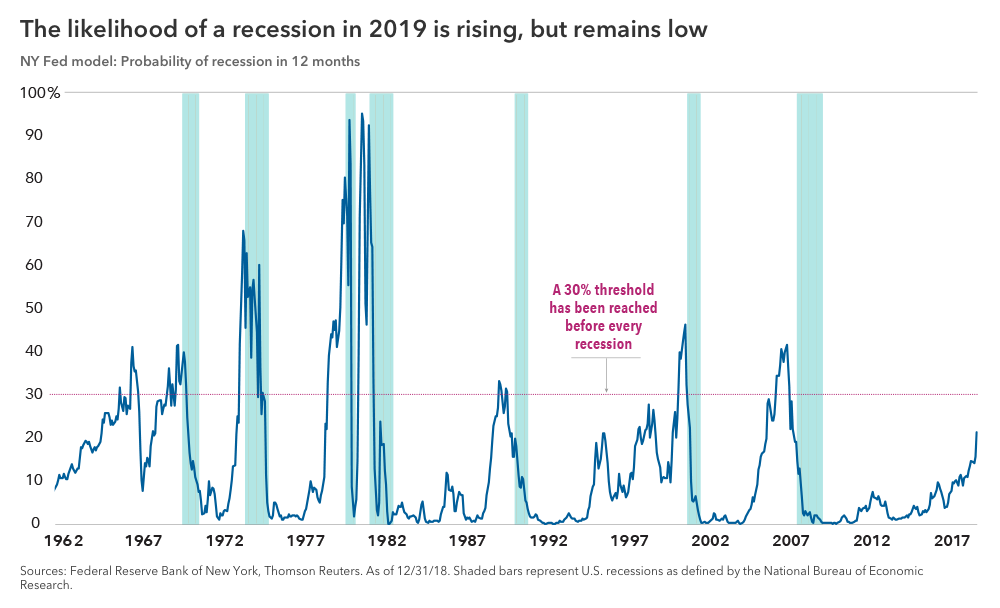

In our view, we don’t believe a recession is imminent in 2019. Our research indicates it is much more likely that the next recession will be in 2020 or 2021. But economic cycles are notoriously hard to predict, and it’s never too early to be prepared for the next downturn.

If the possibility of a recession keeps you up at night, this article ought to put you at ease. That’s because once you read this research about the last 10 downturns you’ll see that recessions may not be as bad as you might think.

1. What is a recession?

Recessions are commonly defined as at least two consecutive quarters of declining GDP after a period of growth. More formally, the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) defines a recession as "a significant decline in economic activity spread across the economy, lasting more than a few months, normally visible in real gross domestic product (GDP), real income, employment, industrial production and wholesale-retail sales." In this guide, we will use NBER’s official dates.

2. What causes recessions?

Past recessions have occurred for many reasons, but typically are the result of imbalances that build up in the economy and ultimately need to be corrected. For example, the 2008 recession was caused by excess debt in the housing market, whereas the 2001 contraction was caused by an asset bubble in technology stocks.

Although every cycle is unique, some common causes of recessions include rising interest rates, inflation and commodity prices. Anything that broadly hurts corporate profitability enough to trigger job reductions also can be responsible.

When unemployment rises, consumers typically reduce spending, which further pressures economic growth, company earnings and stock prices. These factors can fuel a vicious negative cycle that topples an economy.

3. How long do recessions last?

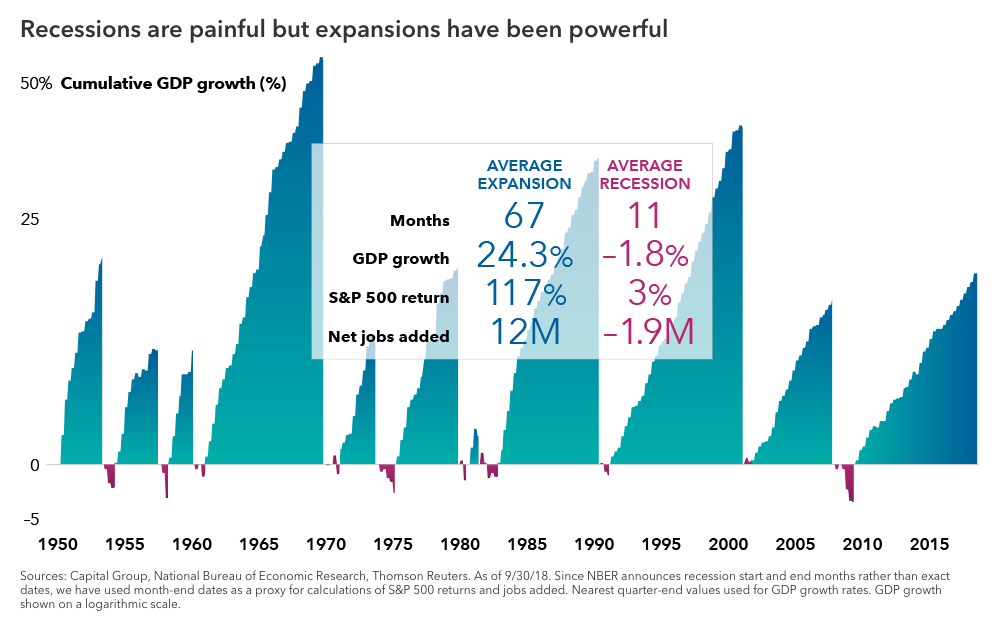

The good news is that recessions generally aren’t very long. Our analysis of 10 cycles since 1950 shows that recessions have lasted between eight and 18 months, with the average spanning about 11 months. For those directly affected by job loss or business closures, that can feel like an eternity. But investors with a long-term investment horizon would be better served looking at the full picture.

Recessions are relatively small blips in economic history. Over the last 65 years, the U.S. has been in an official recession less than 15% of all months. Moreover, the net economic impact of most recessions is relatively small. The average expansion increased economic output by 24%, whereas the average recession reduced GDP by less than 2%. Equity returns can even be positive over the full length of a contraction, since some of the strongest stock rallies have occurred during the late stages of a recession.

4. What happens to the stock market during a recession?

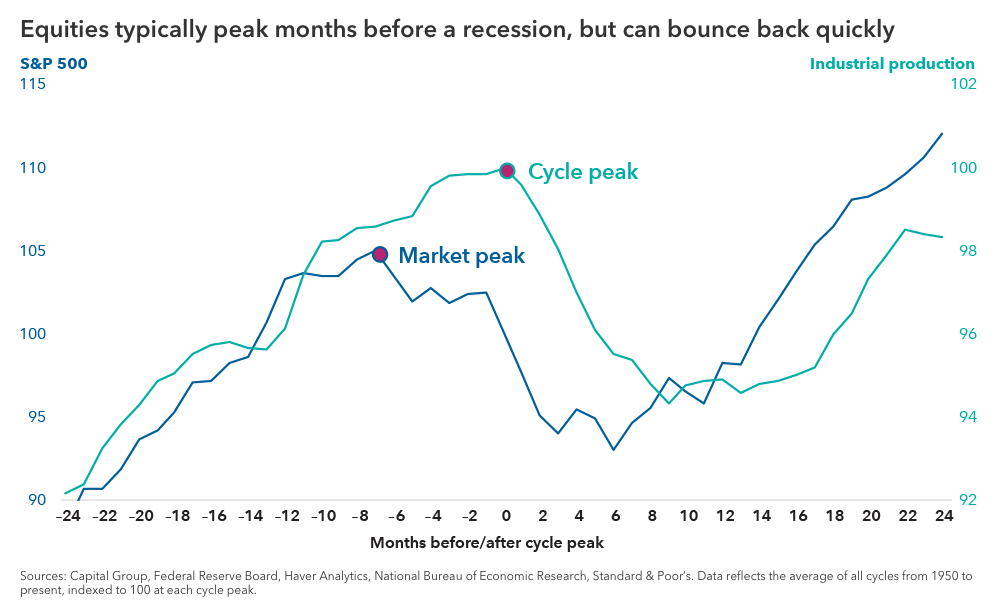

Even if a recession does not appear to be imminent, it’s never too early to think about how one could affect your portfolio. That’s because bear markets and recessions usually overlap at times — with equities leading the economic cycle by six to seven months on the way down and again on the way up.

During a recession, the stock market typically continues to decline sharply for several months. It then often bottoms out about six months after the start of a recession, and usually begins to rally before the economy starts humming again. (Keep in mind, these are market averages and can vary widely between cycles.)

Aggressive market-timing moves, such as shifting an entire portfolio into cash, can backfire. Some of the strongest returns can occur during the late stages of an economic cycle or immediately after a market bottom. It’s often better to stay invested to avoid missing out on the upswing.

5. What economic indicators can warn of a recession?

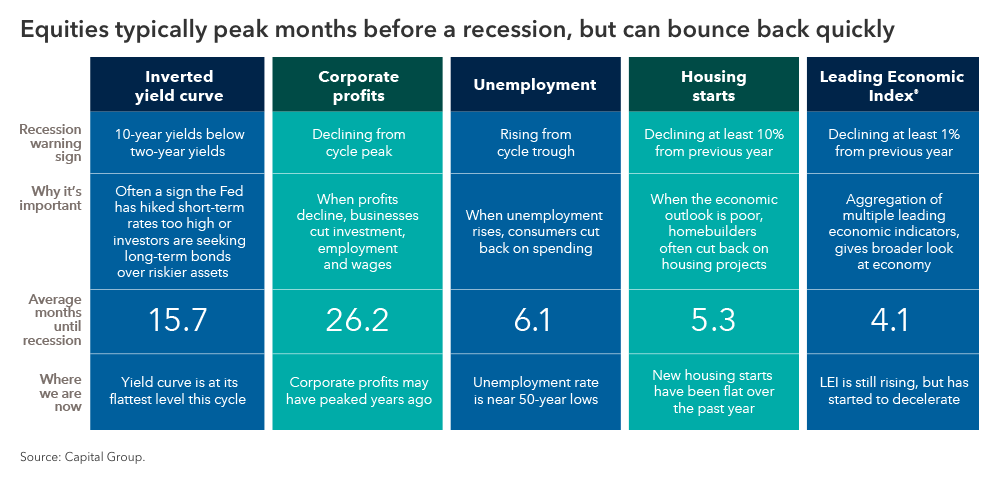

Wouldn’t it be great to know ahead of time when a recession is coming? Despite the impossibility of pinpointing the exact start of a recession, there are some generally reliable signals worth watching closely in a late-cycle economy.

Many factors can contribute to a recession, and the main causes often change. Therefore, it’s helpful to look at several different aspects of the economy to better gauge where excesses and imbalances may be building. Keep in mind that any indicator should be viewed more as a mile marker than a distance-to-destination sign.

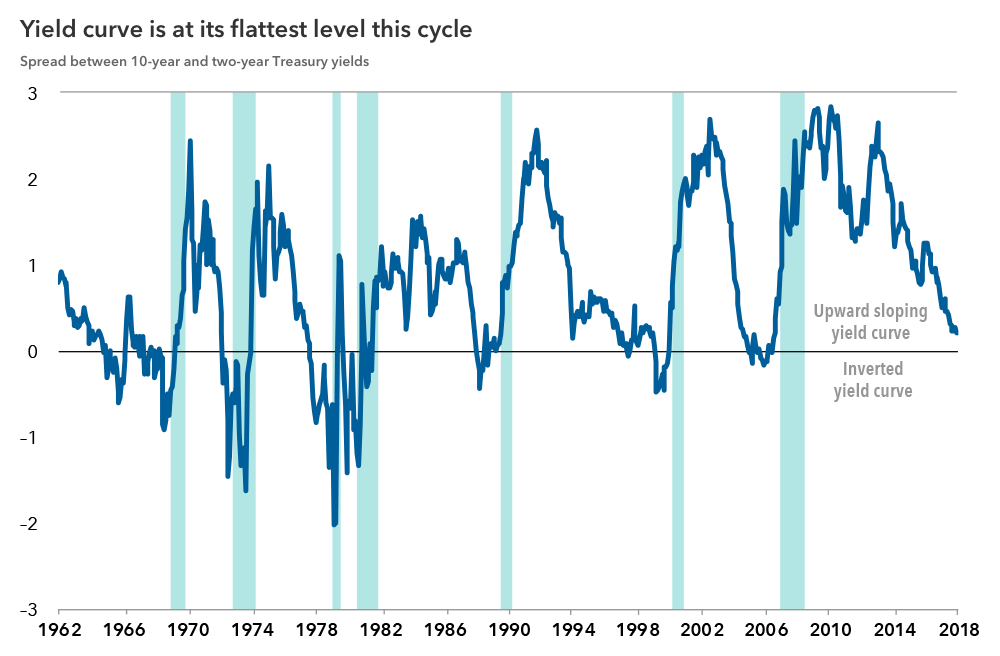

Four examples of economic indicators that can warn of a recession include the yield curve, corporate profits, the unemployment rate and housing starts. Aggregated metrics, such as The Conference Board’s Leading Economic Index®, have also been consistently reliable over time. We’ll highlight one of the most well-known signals — the inverted yield curve.

An inverted yield curve may sound like an elaborate gymnastics routine, but it’s actually one of the most accurate and widely cited recession signals. The yield curve inverts when short-term rates are higher than long-term rates.

This market signal has preceded every U.S. recession over the past 50 years. Short-term rates typically rise during Fed tightening cycles. Long-term rates can fall when there is high demand for bonds. An inverted yield curve is a bearish signal, because it indicates that many investors are moving to the perceived safe haven of long-term government bonds rather than buying riskier assets.

In December 2018, the yield curve between two-year and five-year U.S. Treasury notes inverted for the first time since 2007. Other parts of the curve — such as the more commonly referenced two-year/10-year yields — have not inverted thus far.

Even an inverted yield curve in that range is not cause for immediate panic, as there typically has been a significant lag (16 months on average) before the start of a recession.

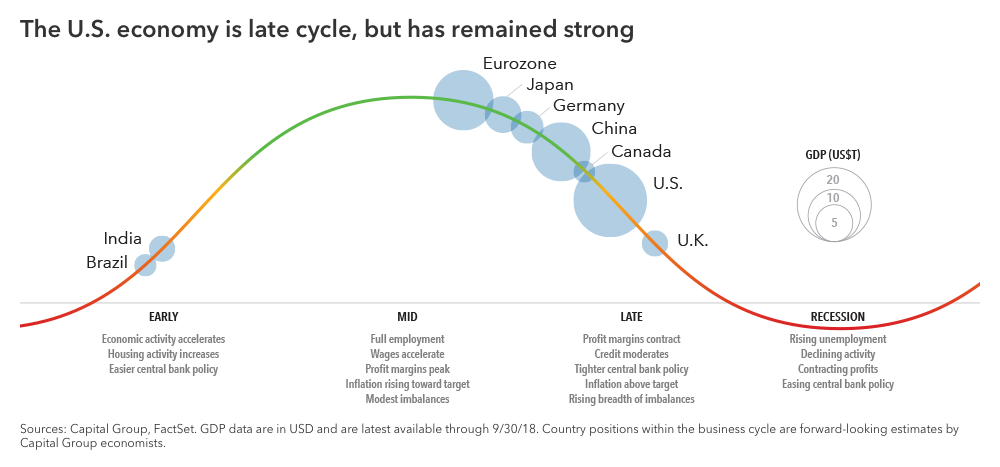

6. How close are we to the next recession?

Economic indicators are a way to take the temperature of the U.S. economy. One or two negative readings could be meaningless. But when several key indicators start flashing red for a sustained period, the picture becomes clearer and far more significant. In our view, that time has not yet arrived.

Although some imbalances are developing, they don’t seem extreme enough to derail economic growth in the near term. The culprit that ultimately sinks the current expansion may one day be obvious: Rising interest rates, higher inflation, or unsustainable debt levels can be major triggers.

These events, if they continue, suggest that the economy could weaken in the next two years, placing a 2020 recession on the horizon. But we are not there yet.

7. How should you position your stock portfolio for a recession?

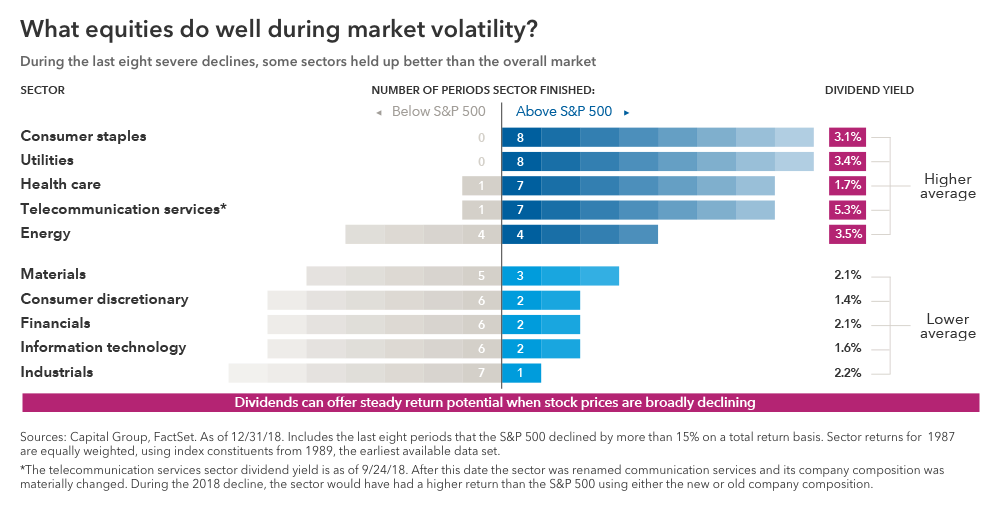

We’ve already established that equities often do poorly during recessions, but trying to time the market by selling stocks can be ill-advised. So should investors do nothing? Certainly not.

To prepare for a recession, investors should take the opportunity to review their overall asset allocation — which may have changed significantly during the bull market — to ensure that their portfolio is balanced and broadly diversified.

Not all stocks respond the same during periods of economic stress. Through the last eight major declines, some sectors held up more consistently than others — usually those with higher dividends such as consumer staples and utilities. Dividends can offer steady return potential when stock prices are broadly declining.

Growth-oriented stocks still have a place in portfolios, but investors may want to consider companies with strong balance sheets, consistent cash flows and long growth runways that can withstand short-term volatility.

Even in a recession, many companies remain profitable. Focus on companies with products and services that people will continue to use every day such as telecommunication services and food manufacturers.

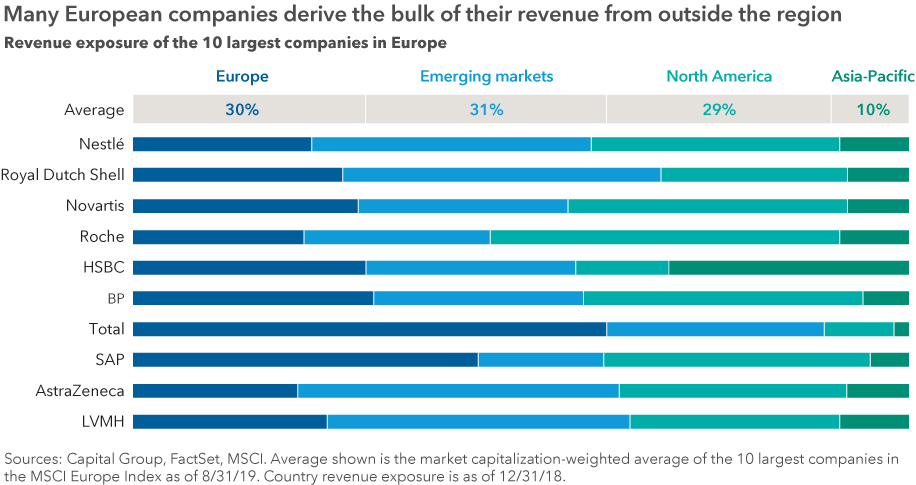

Another way to potentially diversify your portfolio is with international equities. In fact, research shows that the companies with the best annual returns have been mostly based outside of the United States. In the last decade, an average of 74 percent of the top 50 company stocks are based outside of the U.S.

For example, even though European economies are in a period of subdued economic growth, the top 10 largest European companies are thriving. Less than a third of their revenue comes from their home region. The key is to follow the money, not the mail.

Certainly, a recession in the U.S. as one of the world’s biggest economies would be felt in other parts of the globe. But a good strategy could be targeting specific international companies that are generating business in places with underserved and growing middle classes (India and China, for example).

Is there a better equity approach?

8. How should you position your bond portfolio for a recession?

Fixed income is key to successful investing during a recession or bear market. That’s because bonds can provide an essential measure of stability and capital preservation, especially when equity markets are volatile.

Achieving the right fixed income allocation is always important. But with the U.S. economy in late-cycle territory, it’s critical for investors to ensure that core bond holdings provide balance to their portfolio. Investors don’t necessarily need to increase their bond allocation ahead of a recession, but they should make certain that their fixed income exposure provides elements of the four roles that bonds play: diversification from equities, income, capital preservation and inflation protection.

Do your bonds really have you covered?

9. What should you do to prepare for a recession?

Above all else, investors should stay calm and keep a long-term perspective when investing ahead of and during a recession. Emotions can be one of the biggest roadblocks to strong investment returns, and this is particularly true during periods of economic and market stress.

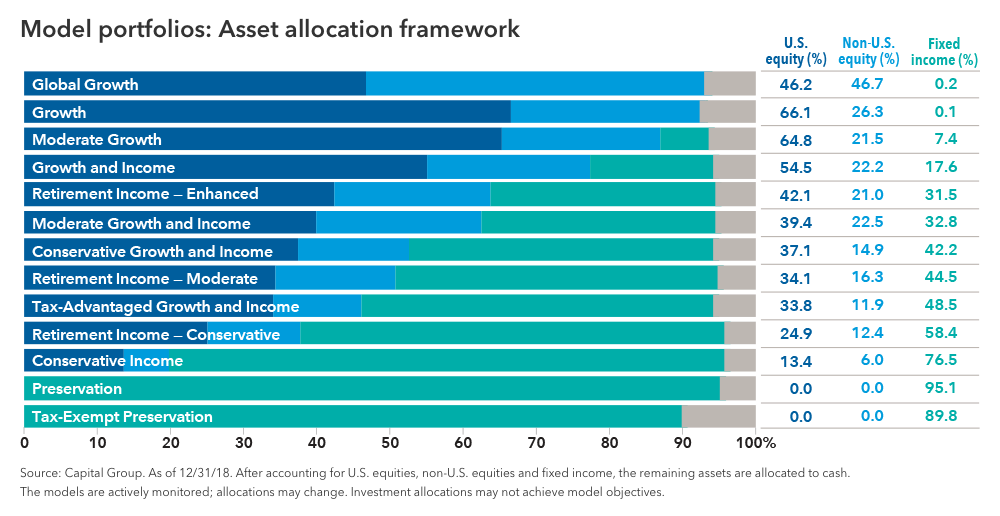

As bottom-up investors, Capital Group doesn’t make explicit asset allocation recommendations. Still, our Model Portfolio Series can be a useful snapshot of examples of balance between U.S. equity, non-U.S. stocks and fixed income for various risk profiles and portfolio goals. Our investment team believes a balanced and broadly diversified portfolio is the best way to pursue strong investment results.

If you’ve picked up anything from reading this guide, it’s probably that determining the exact start date of a recession is ultimately impossible. That’s why aggressive portfolio moves to time the market are rarely a wise decision.

The next recession will come eventually. According to our models, it could be in the next year or two. Whenever it starts, the best way to prepare for a recession is to make sure your portfolio is designed to be balanced enough to benefit from periods of growth before it happens, while being resilient during those inevitable periods of volatility.

More in this series: Upgrade your core portfolio

Is there a better equity approach?

Do your bonds really have you covered?

The Standard & Poor’s 500 Composite Index is a market capitalization-weighted index based on the results of approximately 500 widely held common stocks. The S&P 500 is a product of S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC and/or its affiliates and has been licensed for use by Capital Group. Copyright © 2019 S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, a division of S&P Global, and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved. Redistribution or reproduction in whole or in part are prohibited without written permission of S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC.

The Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Aggregate Index represents the U.S. investment-grade fixed-rate bond market. Bloomberg® is a trademark of Bloomberg Finance L.P. (collectively with its affiliates, “Bloomberg”).

Use of this website is intended for U.S. residents only.

Jared Franz

Jared Franz

Darrell Spence

Darrell Spence