Markets & Economy

Will M&A play a significant role in the post-pandemic world? Companies often rely on mergers & acquisitions to transform their businesses by buying, selling or divesting assets, and 2021 is shaping up to be a big year for deal making.

M&A activity hit $484.5 billion for January and February, up 33% compared to last year.

“Watching companies get acquired or become acquirers is one of my favorite aspects of small-cap investing,” says Greg Wendt, co-president of SMALLCAP World Fund®. “It’s fascinating to track small companies and see which ones make it to a much bigger scale.”

M&A is not just a big deal in small cap. It can impact companies across equity and bond markets. With that in mind, Wendt and a few other Capital Group portfolio managers shared their views on 5 key questions about the M&A boom:

1. What’s fueling the rise of M&A?

“Companies have come out of the shell shock of the first half of 2020 and are now more confident about the future,” Wendt says. Many have strong balance sheets and consider M&A as a growth strategy.

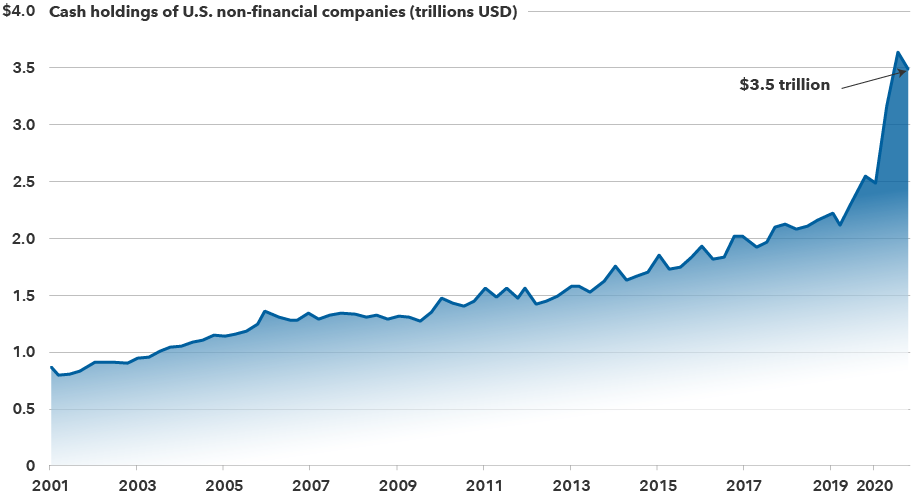

Companies are also sitting on record amounts of cash, says Scott Sykes, a fixed income portfolio manager with American Funds Multi-Sector Income Fund℠. Some industries such as cruise lines and hotel chains raised money to stay afloat through the pandemic. Others — after an initial dash for cash in case of a prolonged downturn — raised additional funds to take advantage of low interest rates.

Many investors expect companies to buy back stock and debt, put funds toward acquisitions, or do a combination of all three, Sykes notes.

Companies have amassed a record amount of cash

Sources: Federal Reserve, Refinitiv Datastream. As of 9/30/20.

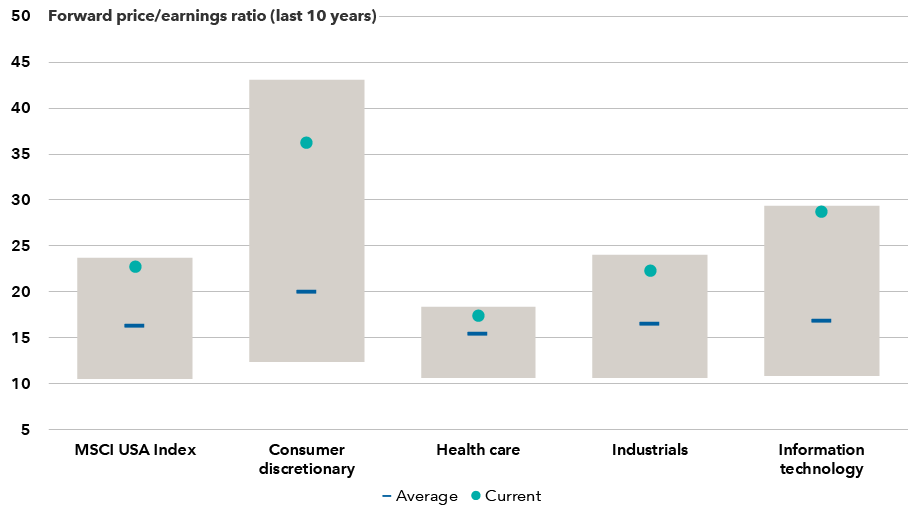

2. Are sky-high equity valuations influencing deals?

“CEOs are a little amazed at their stock prices. They want to use that advantage strategically, and many want to make acquisitions,” Wendt says. “We are in a buoyant market with high stock prices that companies can use as currency.”

Companies that engage in M&A are often those with a history and pattern of deal making. “There are companies you know that make sense as part of bigger companies. And every now and then you’re surprised when the acquirer gets acquired,” Wendt adds.

Meanwhile, companies with more leverage, such as those in the high-yield sector, could use this opportunity to go public, according to David Daigle, lead portfolio manager for American High-Income Trust®. “Private equity firms will be minor players when it comes to buying public assets at these valuations,” Daigle adds. “They will, however, bid aggressively for carve out assets that come up for sale as companies seek to reposition their businesses. But paying a 30% premium on top of already high public valuations is not something you’ll see very often.”

Valuations across most industries are high

Sources: RIMES, MSCI. As of 1/31/21.

3. Is M&A good for investors?

While companies often tout value creation as a result of M&A, many end up destroying value, Wendt says. The Harvard Business Review recently warned management that the “once-in-a-generation opportunity to make acquisitions” could lead to deals that ultimately hurt companies.

“I’m not a huge fan of transformative acquisitions — I’ve seen too many that didn’t work,” Wendt says. “Often M&A is a product of a company running out of gas. They fail as often as they succeed.”

“I think big picture, M&A is a key risk to credit,” Sykes adds. “Large deals tend to add leverage and increase risks. M&A is something I am tracking, and I actively avoid or reduce investments in companies I think could lever up dramatically.”

But the right management team can make all the difference. “Many executives love their companies, and it says a lot about their commitment to maximizing shareholder value when they are willing to sell,” says Wendt. “One of my favorite examples is an airline that sold itself at a time when it was doing very well. The CEO said he just did not see a path to becoming a long-term winner in a consolidating industry.”

On the flip side, there have been companies that turned down incredible offers only to languish for decades trying to get back to that higher price.

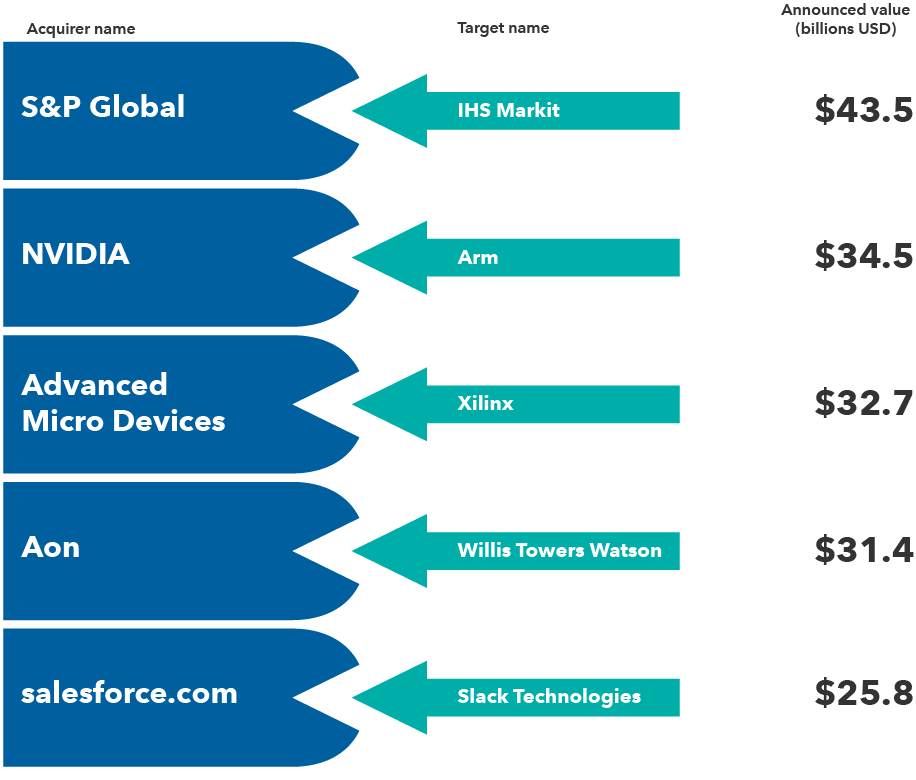

Largest U.S. M&A deals of 2020

Source: Bloomberg. Includes five largest announced deals in 2020 completed or still pending as of 2/28/21.

4. What industries could be most transformed by M&A?

Digitization across all industries will drive many M&A deals. The pandemic accelerated the growth of many tech companies, particularly Big Tech. Although Facebook, Amazon and Alphabet may refrain from acquisitions in the face of intense regulatory scrutiny, there are several smaller tech companies that could become targets or buyers, according to Wendt.

For example, banks have always wanted a slice of the digital payment space, but the pandemic accelerated the move toward contactless payments. Large players such as PayPal continue to make acquisitions but may eventually find themselves a target.

Gaming companies such as casino operators are also on the hunt for digital offerings in the areas of fantasy sports and online betting. “This industry is maturing quickly, and it is much easier to get a known customer to bet more than to identify new customers,” Wendt adds.

Media is also another sector undergoing massive shifts, with cord cutting continuing to drive some of the changes. “There’s a lot more competition creating content, and it’s unclear if some of the programming translates well to streaming,” Sykes notes. “Will Amazon, Netflix, or Disney+ buy content the same way that CBS and ABC once did?”

Meanwhile, Big Pharma’s penchant for acquiring smaller companies with drugs nearing regulatory approval is well-known. This year will be no exception, he adds.

Innovation is particularly fragmented in drug development with many small players working to find solutions to big health care problems. Regulatory pressure to keep costs low and preserve patent expirations on key drugs tend to support M&A activity no matter the economic environment.

In energy, companies may engage in M&A to create a better industry structure that allows them to be profitable, Daigle says. Many are investing in renewables as governments worldwide call for lower emissions, and legacy energy companies are seeking to consolidate amid persistently low energy prices.

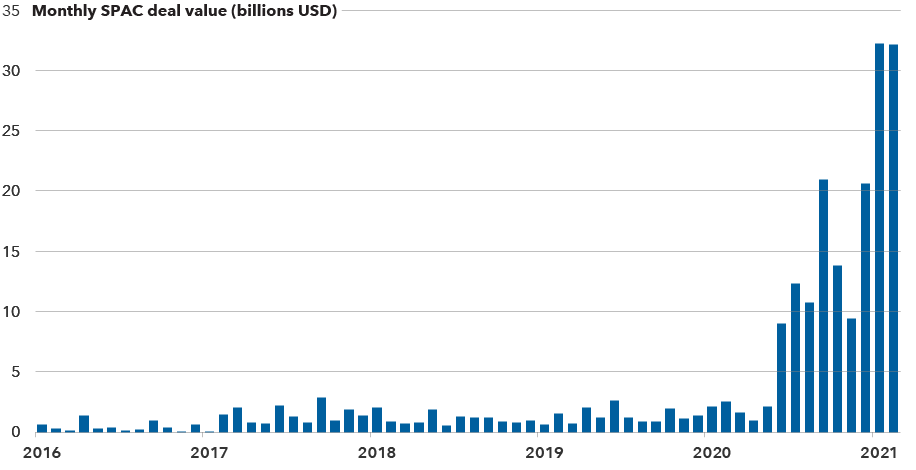

5. How are SPACs changing the game?

The frenzy around special purpose acquisition companies (SPAC) has achieved star status. Shaquille O’Neal and Alex Rodriguez are among the names providing the funding. Even major corporations such as consumer food company Post Holdings and device maker Medtronic are in on the act.

A SPAC allows a private company to become public without going through the lengthy process of filing an initial public offering, or IPO. Here’s how it works: The publicly traded SPAC raises cash via the market and uses the funds to acquire a private company. By comparison, an IPO is when a company files paperwork to raise funds as part of its effort to go public.

More than 380 SPACs raised $106 billion last year. And in January 2021 alone, SPACs raised roughly $32 billion.

SPACs are on the rise

Source: Bloomberg. Includes all announced deals as of 2/18/2021.

The sheer number of active SPACs created in 2020 indicates the pipeline for acquisitions is exceptionally high.

“M&A is going to be really interesting this year because of the rise of SPACs, which generally have two years to find a deal or the money gets returned,” says Wendt, who has already invested in several SPACs. “There are going to be lots of new companies introduced to the market, which is great for an organization with deep research capabilities.”

Investing outside the United States involves risks, such as currency fluctuations, periods of illiquidity and price volatility, as more fully described in the prospectus. These risks may be heightened in connection with investments in developing countries. Small-company stocks entail additional risks, and they can fluctuate in price more than larger company stocks.

The return of principal for bond funds and for funds with significant underlying bond holdings is not guaranteed. Fund shares are subject to the same interest rate, inflation and credit risks associated with the underlying bond holdings. Lower rated bonds are subject to greater fluctuations in value and risk of loss of income and principal than higher rated bonds.

Bond ratings, which typically range from AAA/Aaa (highest) to D (lowest), are assigned by credit rating agencies such as Standard & Poor's, Moody's and/or Fitch, as an indication of an issuer's creditworthiness. If agency ratings differ, the security will be considered to have received the highest of those ratings, consistent with the fund's investment policies. Securities in the unrated category have not been rated by a rating agency; however, the investment adviser performs its own credit analysis and assigns comparable ratings that are used for compliance with fund investment policies.

Bloomberg® is a trademark of Bloomberg Finance L.P. (collectively with its affiliates, “Bloomberg”). Barclays® is a trademark of Barclays Bank Plc (collectively with its affiliates, “Barclays”), used under license. Neither Bloomberg nor Barclays approves or endorses this material, guarantees the accuracy or completeness of any information herein and, to the maximum extent allowed by law, neither shall have any liability or responsibility for injury or damages arising in connection therewith.

The MSCI USA Index is a free float-adjusted, market capitalization-weighted index that is designed to measure the U.S. portion of the world market. The index is unmanaged and, therefore, has no expenses. Investors may not invest directly in an index.

MSCI does not approve, review or produce reports published on this site, makes no express or implied warranties or representations and is not liable whatsoever for any data represented. You may not redistribute MSCI data or use it as a basis for other indices or investment products.

Copyright © 2021 S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, a division of S&P Global, and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved. Redistribution or reproduction in whole or in part is prohibited without written permission of S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC.

To read the full article, become an RIA Insider. You'll also gain complimentary access to news, insights, tools and more.

Already an Insider?

Greg Wendt

Greg Wendt

Scott Sykes

Scott Sykes

David Daigle

David Daigle