Chart in Focus

U.S. Equities

Is there such a thing as being too successful, too influential and just too big? We may find out in the months and years ahead as the world’s largest technology and consumer tech companies come under increasingly aggressive antitrust and regulatory scrutiny.

Government efforts to rein in Big Tech have been underway for years, but 2021 is likely to be a watershed moment due to a number of growing pressures. Political, societal and market-based forces are combining to put these companies — Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Microsoft and others — under the microscope.

“The sheer size of these companies means they're going to get a lot of scrutiny from every part of society, including government and regulatory agencies,” explains Mark Casey, a Capital Group portfolio manager who has covered the tech industry for more than 20 years.

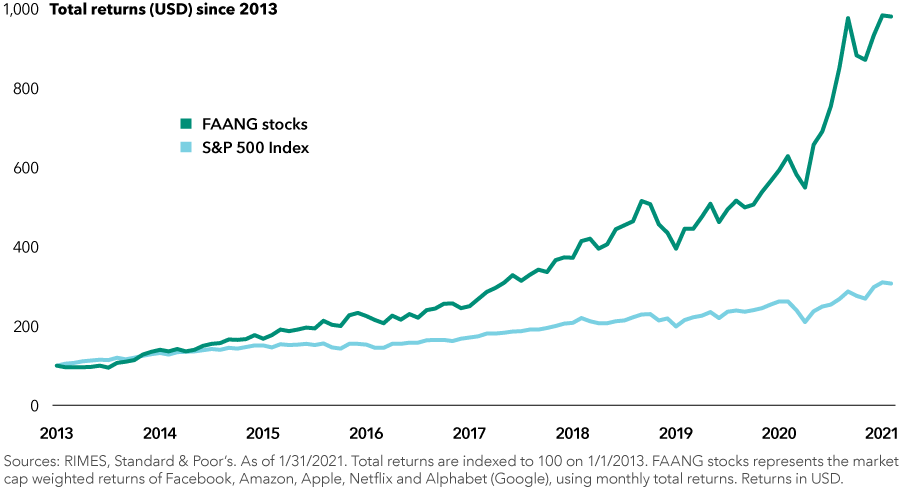

The rise of Big Tech: FAANG stocks have dramatically outpaced the S&P 500 Index

“Some of these companies have also played key roles in the past two U.S. presidential elections,” says Casey, a manager with The Growth Fund of America®. “When you bring politics into the mix, that helps explain why these regulatory discussions are very prominent right now.”

In addition, the COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the growth of many tech companies, increasing their power and influence during a severe global economic downturn. Of the top 10 U.S. companies by market capitalization, five are technology or digital businesses and their total market value exceeds $7 trillion — a figure that has grown by 54% over the past year alone.

Landmark litigation is underway

With that territory comes major league antitrust and regulatory risk:

- In October, the U.S. Department of Justice filed an antitrust lawsuit against Google, alleging the internet search giant stifles competition. It’s the biggest antitrust case since the government targeted Microsoft in 1998.

- In December, the Federal Trade Commission sued Facebook on similar claims that the social media network engaged in anticompetitive practices with its acquisitions of Instagram and WhatsApp.

- Many U.S. states have joined these two landmark legal actions while, at the same time, countless legislative efforts are underway at the state and federal levels.

- A bill introduced in the U.S. Senate last week could make it more difficult for large companies to acquire competitors. In Florida, state lawmakers are considering legislation that would fine social media companies for de-platforming political candidates.

“Part of what makes this so complicated,” Casey notes, “is that Democrats have a whole set of issues with these companies — largely based on antitrust, privacy and hate speech concerns — while Republicans have another set of issues, particularly when it comes to the perceived censorship of conservative viewpoints. So there’s really no easy scenario where these companies can just make a few changes and everybody’s happy.”

Another element accelerating the regulatory push is the recent episode involving a group of retail investors who organized themselves on an internet chat board to drive up the stock prices of GameStop, AMC Entertainment and other struggling companies. When brokerage firms and trading apps imposed trading limits, some of those retail investors lost big. In a rare bipartisan move, Republicans and Democrats have called for Congressional hearings, which are expected to begin next week.

European influence

U.S. politicians and regulators seeking to limit the power of Big Tech can look to Europe for inspiration. European authorities have been far more aggressive in their regulatory efforts, including the threat of huge fines for violating data protection rules and engaging in anticompetitive behavior.

The European Union was the first to enact major online privacy laws in the form of the General Data Protection Regulation, adopted in 2018. EU officials have since followed that up with a series of proposed regulations designed to block certain acquisitions, curb hate speech and provide more information to consumers about how their data may be used for targeted advertising.

“Many of these provisions are already being implemented by U.S.-based internet platforms because of the European regulations,” says Brad Barrett, a Capital Group analyst who covers ad supported internet companies. “Europe doesn’t have many of its own national champions in the social media industry, so it’s perhaps easier for the EU to be more aggressive in this area and for the U.S. to follow when it makes sense.”

So far, Barrett notes, the EU rules haven’t had a major impact on technology companies from a profit or revenue perspective.

FAANGs have proven to be unique while revolutionizing different industries

Regulators face uphill battle

Assessing the regulatory risks faced by large tech companies is a complex task, Barrett explains, given that they operate in different industries with vastly different competitive profiles — everything from retail to advertising to television. That said, in his assessment, the antitrust cases against Google and Facebook aren’t strong and likely won’t result in any forced breakups.

The government is facing “an uphill battle” to win these cases, Barrett says, evidenced by the fact that some members of Congress are pushing hard for changes in antitrust law.

“That by itself is an admission that it’s difficult to find antitrust violations based on case law going back 20 to 30 years,” he adds.

Not to mention that many of the products provided by Google and Facebook are free, diminishing traditional antitrust arguments that rely on pricing power to help determine monopoly status.

Is regulatory risk already “priced in”?

How should investors evaluate the outlook for Big Tech, given the potential for some sort of government intervention in the years ahead? One important question to ask is: Do company valuations reflect the risk? In other words, are they “priced in” to the stocks?

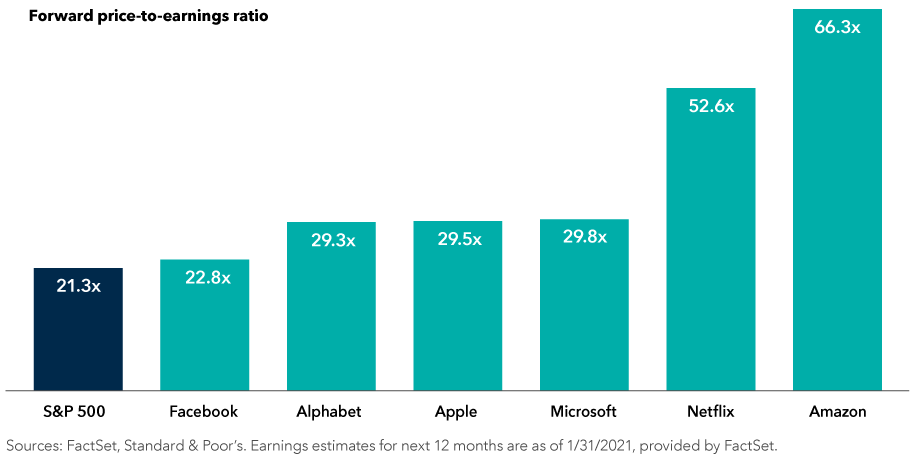

Looking at the FAANG stocks as a bellwether for regulatory risk, the two companies that are currently at the center of high-profile lawsuits — Facebook and Alphabet — are trading at significantly lower price-to-earnings ratios than, for example, Amazon and Netflix. In fact, Facebook is trading just above the average P/E for the Standard & Poor’s 500 Composite Index despite its rapid growth rate and strong free cash flow.

Valuations for some Big Tech companies don’t look excessive

Last week, Facebook reported a fourth-quarter profit of $11.2 billion, a 52% increase from the same period a year ago. Alphabet, which trades at a slightly higher P/E than Facebook, reported a quarterly profit of $15.7 billion, up 40% from a year ago.

“These companies operate in large and growing markets, they have long revenue runways and they are very profitable,” explains Capital Group analyst Tracy Li, who covers internet companies. “If the regulatory risks were not present, in my view, they would be trading at higher multiples.”

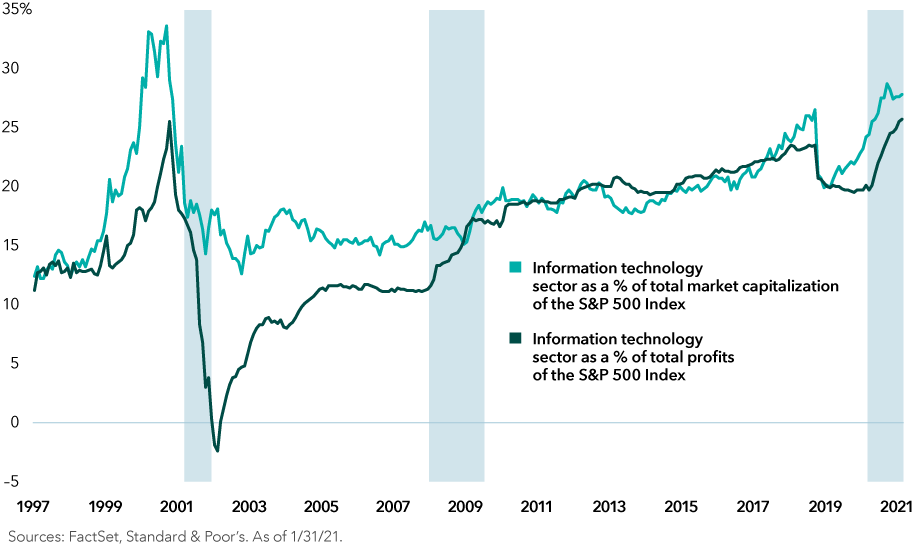

Unlike the dot-com bubble, tech company profits are more in line with prices

Breakup risk: The parts may be greater than the whole

In the unlikely event that one or more of these companies is forced to break up, a reasonable argument could be made that some of the spinoffs could be worth more on their own, Li notes. Indeed, sometimes the parts can be worth more than the whole.

WhatsApp, for instance, which was acquired by Facebook in 2014, currently does not make money. But as a stand-alone company, it would likely command a high valuation due to its user base of more than 2 billion people in 180 countries and the opportunity to monetize the service in the future. The same could be said for Instagram and Facebook Messenger.

“The fact that all of these businesses are under one umbrella does tend to obscure the value of each business,” Li says. “As we’ve seen with past antitrust cases, such as the breakup of AT&T or Standard Oil, the results can be quite favorable to shareholders over the long run.”

Investing outside the United States involves risks, such as currency fluctuations, periods of illiquidity and price volatility, as more fully described in the prospectus. These risks may be heightened in connection with investments in developing countries. Small-company stocks entail additional risks, and they can fluctuate in price more than larger company stocks.

The market indexes are unmanaged and, therefore, have no expenses. Investors cannot invest directly in an index.

Standard & Poor’s 500 Composite Index is a market capitalization-weighted index based on the results of approximately 500 widely held common stocks.

The Standard & Poor’s 500 Composite Index is a product of S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC and/or its affiliates and has been licensed for use by Capital Group. Copyright © 2021 S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, a division of S&P Global, and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved. Redistribution or reproduction in whole or in part are prohibited without written permission of S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC.

Mark Casey

Mark Casey

Brad Barrett

Brad Barrett

Tracy Li

Tracy Li