China

It’s important to state up front that we don’t believe China is “un-investible” as some have posited following the government’s recent intervention into several areas of the private-sector economy. It’s also not a geopolitical pariah like Russia, which is a tiny constituent of the global indexes and economy.

China’s key attraction is its enormous domestic market. But as the world’s second-largest economy, China is deeply interconnected with the global economy in manufacturing supply chains and is increasingly a large portion of multinational corporate revenues. Understanding and navigating the complexities of China has important implications for both domestic and international investing in understanding the development of its capital markets longer term.

The framework for investing in China has changed significantly over the past year due to micro, macro, regulatory and geopolitical factors. China is still investible, but at the right price in the right sectors. And the kinds of companies that might be future potential sources of solid returns could be quite different than in the past decade.

With that backdrop in mind, here is how we are thinking about investing in China today.

The risk premium is higher

We’ve been significantly reassessing the risk premium applied to China, given slower economic growth, the rising demographic headwinds and the potential for further regulatory measures. The country is going through a structural change during a cyclical downturn, and it could take some time to fully understand the impact of the government’s common prosperity agenda for the economy and President Xi Jinping’s priorities if he secures a third term.

So, what do we know? From our perspective, China’s problems are fairly apparent: among them, an aging population, significant debt at state-owned enterprises and local governments, pollution, wealth disparity and inefficient allocation of capital. The property sector and its current downturn are of particular concern.

Xi is trying to fix many of these critical problems with reforms and regulations. And since China’s two-term limit on the presidency was removed in 2018, Xi is widely expected to be elected for a third term at the 20th Party Congress in late 2022, giving him more time to implement his agenda and shape China for decades to come.

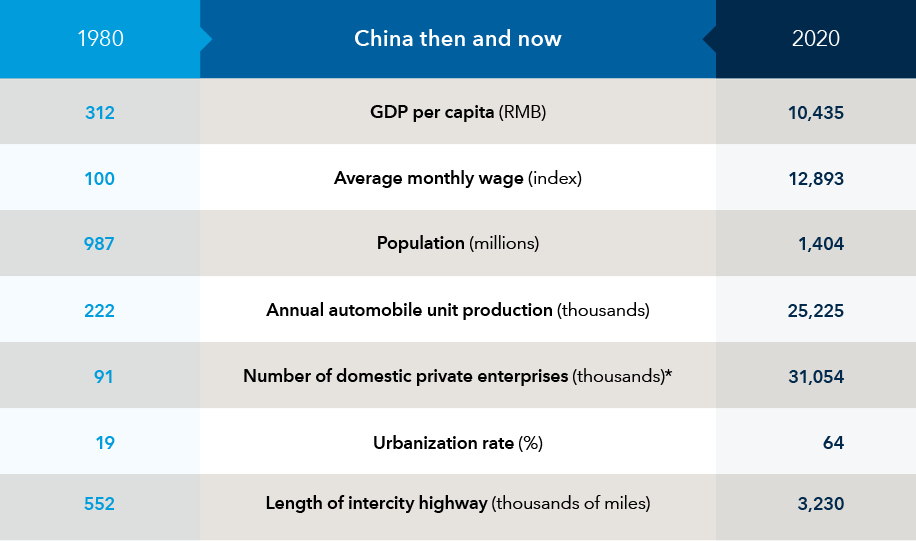

Explosive growth has transformed China over 40 years

Sources: Capital Group, CEIC Data, IMF Data, the World Bank. *Data for number of private enterprises as of 1988 and 2018. (RMB is the abbreviation for China's currency, the renminbi.)

For now, it means companies with excessively high profit margins may come under scrutiny, similar to what happened in the for-profit education and technology-related sectors. It also means incorporating a much more layered and complex analysis of each security from a fundamental perspective and through a policy lens to see where it fits in Beijing’s development agenda. An example would be companies that are beneficiaries aligned with Xi’s mandate to source locally and develop internal domestic supply chains.

It further means applying a higher risk premium to Chinese equities with comparable businesses to listed stocks in other countries that don’t have the same political risks. Emerging internet platform companies in Southeast Asia and Latin America are an example.

Over the past 18 months, we’ve become more selective and have narrowed exposure in China. Holdings have become increasingly concentrated in fewer larger positions and in companies run by private entrepreneurs, where there remains potential for secular growth with some political tailwinds.

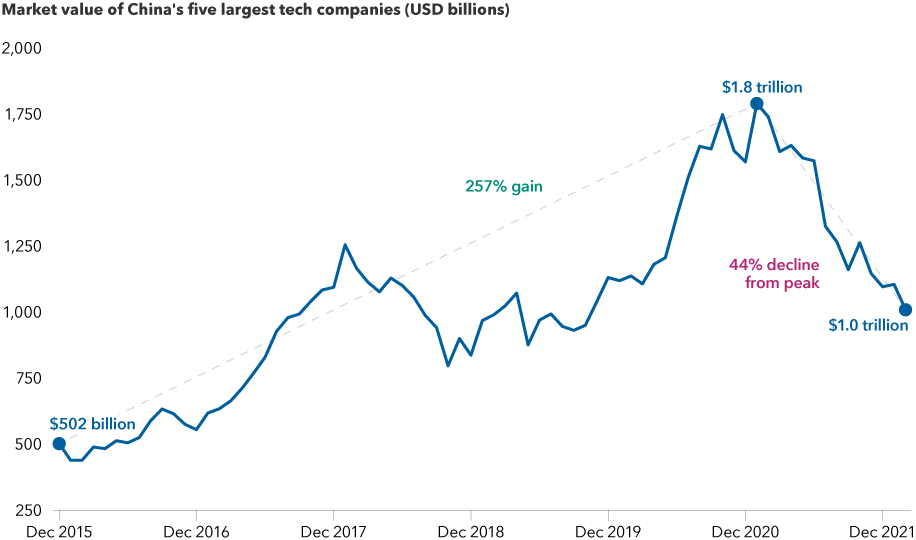

And we’ve become more valuation sensitive and focused on capital allocation. This has meant a reduction in technology holdings and China exposure overall. As the chart shows, China’s technology companies have tumbled since early 2021, not long after China’s regulators abruptly postponed the initial public offering of Alibaba affiliate Ant Financial.

Value of China’s technology giants has diminished on regulatory uncertainties

Sources: Capital Group, MSCI, RIMES. The five companies included represent the five largest Chinese technology companies (Tencent, Alibaba, JD.com, Baidu and NetEase) by market value as of February 28, 2022, that were also publicly listed in 2015. All stocks, except Tencent, reflect their American Depository Receipts.

A focus on domestic companies with less political risk

Finding areas to invest alongside the priorities of China’s government has taken on even greater importance. The government seems determined to not let private companies have a disproportionate influence on any single area of the economy or to reap high profits at the expense of consumers, although they want them to remain innovative and source materials domestically.

It seems the playbooks for the large internet platform companies has changed and their days of exponential growth will be more measured. To some degree, this is now reflected in their stock prices. It’s become clear the government wants to prevent the large technology companies from aggressively expanding horizontally into multiple lines of business. It also seems clear the government wants to protect their smaller competitors and to force a more equitable distribution of wealth.

On top of this, several key areas, like e-commerce, may be maturing in terms of penetration and have become increasingly competitive. Based on reports of layoffs and bonus cuts in China’s internet sector, it appears these companies are preparing for a different future.

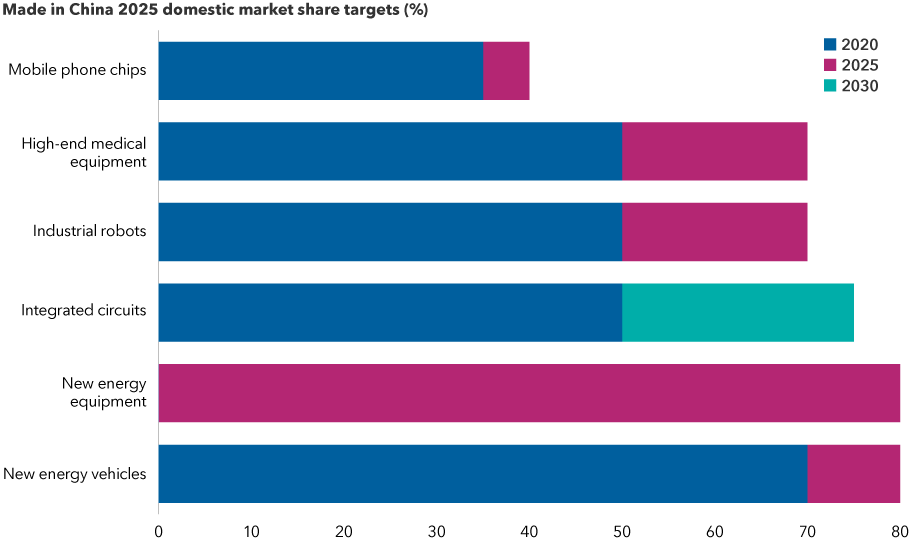

In our view, political investment risk may be reduced by focusing on domestic-oriented companies in China that are aligned with Xi’s policy priorities (i.e., automation, local technology and content, environment, electric vehicles (EVs), health care) and serve to improve people’s lives at reasonable prices and margins.

Over the years, we’ve met many smart entrepreneurs in China who have scaled up their businesses very quickly and believe such investment opportunities remain in the country’s large addressable markets, in areas like consumer products, health care, IT services, semiconductors and clean energy. So, from our perspective, it is possible to enjoy a long tailwind of growth if you pick the right place to invest.

China seeks to become self-sufficient in key industries

Sources: U.S. Chamber of Commerce and the Center for Security and Emerging Technology, based on estimated data as of 2017.

Potential areas of growth alongside the government’s agenda

One area of interest is auto dealerships, which are building their brands within China. It’s a basic business but still largely fragmented across China with room to grow, especially in after-sales service. EVs and urban natural gas networks that replace coal are attractive areas that are aligned with the government’s agenda. And, given the aging population, automation and health care remain areas with long-term tailwinds. Other areas of potential growth are national consumer brands in the alcohol and dairy space, which are gaining share and have pricing power.

Given the sheer size of the population, domestic consumer brands don’t necessarily have to target consumers outside China to become successful. Many Chinese consumers are buying their first homes, refrigerators and other household appliances to improve their living standards, and the middle class continues to grow and remains aspirational. This approach also helps shield some investments from getting swept up in U.S.–China trade frictions.

Expect a slower rate of growth in China’s economy

There is a risk of a prolonged slump in China’s economy. China is dealing with another round of rolling COVID-19 lockdowns (which are more stringent than those in 2020), and this could further constrain already weak consumer spending and a broader reopening of China’s economy. This also may continue to impact global supply chains and increase global inflationary pressures.

The property market, which is a significant contributor to the country’s gross domestic product (GDP), is in a significant downturn with many heavily indebted real estate developers. Land and home sales have been weak, and there does not seem to be much incentive for buyers to fork over down payments on projects that might not get finished.

Our economist colleague Stephen Green is concerned about the prospects for China’s economy over the next 12 months. He anticipates marginal growth and does not expect any significant loosening of policy that would forestall the current slowdown. He believes Beijing, which has guided to 5.5% GDP growth in 2022, has not done enough fast enough to turn around the economy.

There are likely to be a few interest rate cuts and tax cuts for small businesses, but no big bang measures like those that pulled China out of its 2015–16 slump. At best, in Green’s estimation, Beijing will slowly turn up the stimulus dial each month.

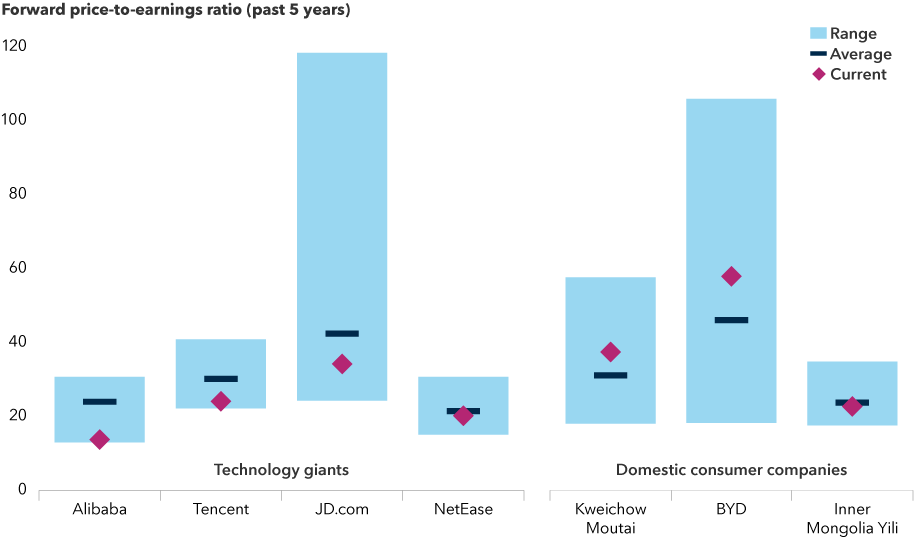

Valuations for leading domestic consumer companies have been less affected

Source: Refinitiv Datastream. Data as of February 28, 2022. Forward price-to-earnings is the ratio for valuing a company that measures its current share price relative to its projected per share earnings over the next 12 months.

Historically, volatility in China has been a buying opportunity: The problem appears, growth slows, the government comes up with clever tweaks to regulation and policy with more stimulus, the economy stabilizes and the market rebounds. But it seems the playbook has changed, and many of us are waiting to see if more significant stimulus measures happen after the 20th Party Congress.

The energy shortages that rippled through China in the fall of 2021 and temporarily shut down manufacturing facilities were telling about Xi’s resolve to restructure the economy. Why would Xi allow this when the economy was weak, the property market was rapidly decelerating, there was a trade war with the United States and COVID was impacting global export markets?

The message is clear, in our view: GDP growth is no longer a top priority for China’s Communist Party. We are bracing for more volatility and plan to be more selective about gauging the risk premium for industries and companies. But we continue to look for longer term opportunies amid this market selloff.

Investing outside the United States involves risks, such as currency fluctuations, periods of illiquidity and price volatility. These risks may be heightened in connection with investments in developing countries. Small-company stocks entail additional risks, and they can fluctuate in price more than larger company stocks.

MSCI has not approved, reviewed or produced this report, makes no express or implied warranties or representations and is not liable whatsoever for any data in the report. You may not redistribute the MSCI data or use it as a basis for other indices or investment products.

Use of this website is intended for U.S. residents only.

Christopher Thomsen

Christopher Thomsen

Kent Chan

Kent Chan