China

While Western economies are tightening monetary policy, China is taking steps to stimulate its economy. Government officials have made marginal interest-rate cuts, extended huge tax credits to businesses, accelerated local government bond issuance and loosened restrictions on home buying.

Will these measures jump-start the world’s second-largest economy? I am not counting on a swift turnaround.

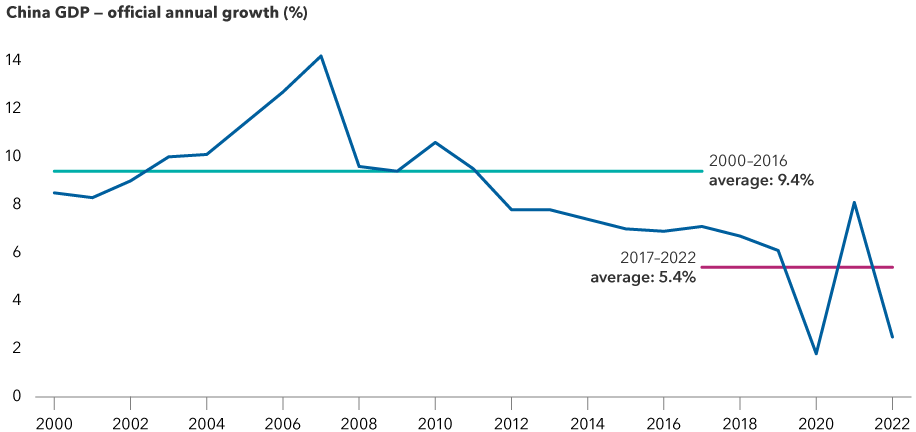

In the second quarter, China’s economy grew at its slowest pace since early 2020 and narrowly escaped a recession, based on official government data. While members of our investment team continue to see some attractive long-term investment opportunities in China, particularly those more aligned with government policies, I believe the economy will continue to struggle in the near term, and the recovery will take time. Here are a few reasons:

1. Lockdowns likely to continue into 2023

After leading the world’s economic rebound from the depths of the COVID-19 pandemic two years ago, China’s economy has been roiled by rolling lockdowns under the government’s strict “dynamic zero-COVID” policy — the only one of its kind in the world.

This has impacted some of the country’s key manufacturing and shipping hubs, including Shanghai, where residents and businesses endured a recent two-month lockdown. The effects seem to have spread far into the surrounding provinces, too. The lockdowns have also tripped up global supply chains and hurt business confidence among multinationals operating in the country.

China’s economy has slowed after explosive growth

Sources: Capital Group, National Bureau of Statistics of China, Refinitiv Datastream. Gross domestic product (GDP) reflects constant prices. Data for 2022 is as of June 30, 2022.

It seems evident that the government will not tolerate a large-scale COVID outbreak at this stage, and the risk remains high for more lockdowns. But it’s possible future lockdowns could be smaller in scale and less restrictive.

Overall, I would say there is a 50-50 possibility that party officials shift away from their zero-COVID approach in the spring of 2023. Either way, this could have serious ramifications on manufacturing output, global commodities demand and consumer spending.

2. The housing market is facing acute challenges

The property sector, which accounts for close to 30% of China’s gross domestic product (GDP) when all related inputs are included — and has, until recently, been an engine of economic growth — now faces challenges on multiple fronts. Recent reports of homebuyers threatening to stop making mortgage payments on unfinished apartment projects is the most recent and acute setback. The movement sparked a selloff in publicly listed Chinese real estate companies and banks, and is rumored to have affected more than 300 projects in various parts of the country.

(It’s common in China to start paying interest on the mortgage as soon as buyers put down a deposit, and they usually must wait one to two years for the developer to finish construction.)

While China’s banking regulator has reportedly pledged to help developers and work with local provincial governments, I think the odds are quite low that the Ministry of Finance will issue bonds to help cover the financing shortfalls of private developers. Moreover, it’s not easy to just hand the projects over to local state-owned developers.

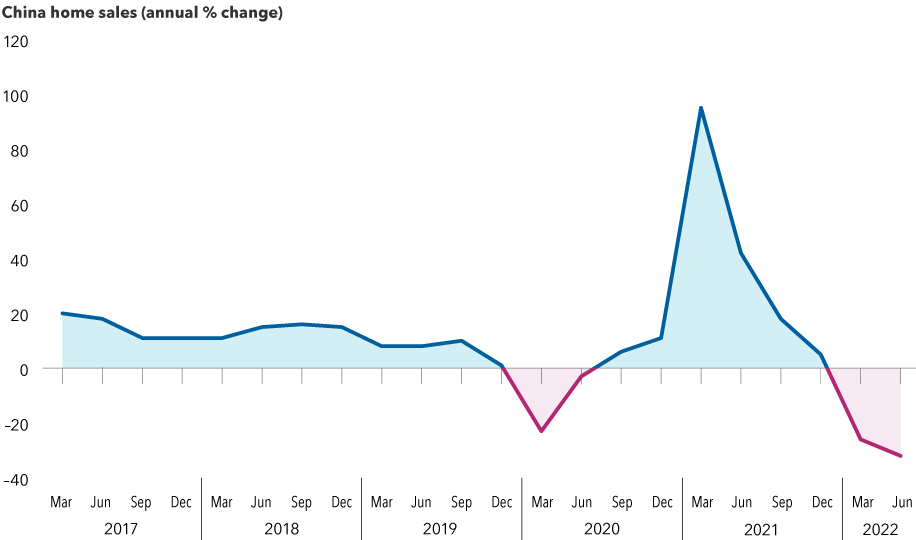

The strong surge in housing sales in the first two weeks of June as lockdowns eased seems to have been a short blip. I do not expect sales to recover in the second half of 2022.

Home sales in China have slumped

Sources: Capital Group, National Bureau of Statistics of China, Refinitiv Datastream. China home sales above are represented by the quarterly sales volume of commercial residential buildings at current prices. As of June 30, 2022.

Looking out to the next two to three years, the big question is how much latent housing demand is still out there. China is still urbanizing — the current urban occupancy rate of nearly 65% will likely continue to rise to 75% or 80%. But new urbanites and urban dwellers looking to upgrade to bigger, nicer housing face high prices, especially in big cities. Given the government’s attempt to gradually deflate what could be a bubble, the investor buyer base will probably diminish. They made up some 20% of demand in recent years, according to surveys. So, in my view, annual sales will probably contract from here.

In terms of policy, hundreds of city-level governments have reversed buying restrictions in the past year, including reducing down payments, removing requirements to live in a city to qualify to buy and providing greater access to employee housing funds.

To help stimulate demand, Beijing has been offering housing coupons in approximately 20 cities. The vouchers give individuals an opportunity to purchase a place at a discounted rate. However, this loosening has failed to reignite interest. That’s likely the result of several reasons: slow wage growth and worries about the future, COVID-related lockdowns and worries about developers’ financial health. I think authorities will need to do more to loosen those restrictions and relax the dynamic zero-COVID policy before we see a recovery.

Furthermore, inventories of unsold homes are high, especially outside the biggest cities. Most developers are still in financial difficulty, especially the privately owned ones. Therefore, I believe that, without a sales recovery, risks in the housing market will continue to rise.

3. Exports likely to slow further

While China’s dependence on exports has declined over the years, they still make up about 15% of GDP and accounted for 40% of economic growth last year. With the economies of the United States and Europe slowing down and possible slipping into recession, exports are flat year on year and could even contract.

The renminbi has weakened about 6% this year against the U.S. dollar, which has strengthened against almost all currencies. As a result, the trade-weighted renminbi is pretty strong. A weak domestic economy means that imports could slow in 2023, alongside exports, so China’s trade surplus is likely to remain very large. That is supportive of the renminbi.

But if the domestic economy continues to struggle on several fronts, it is possible that we see a revival of large-scale financial account outflows, as we did in 2015. (The financial account is part of a country's balance of payments. It measures increases or decreases in international ownership of assets.)

So, I think that the renminbi could weaken against the dollar in the next six to 12 months, and could possibly break the 7.0 renminbi-to-the-dollar barrier.

4. There may not be a big fiscal stimulus package

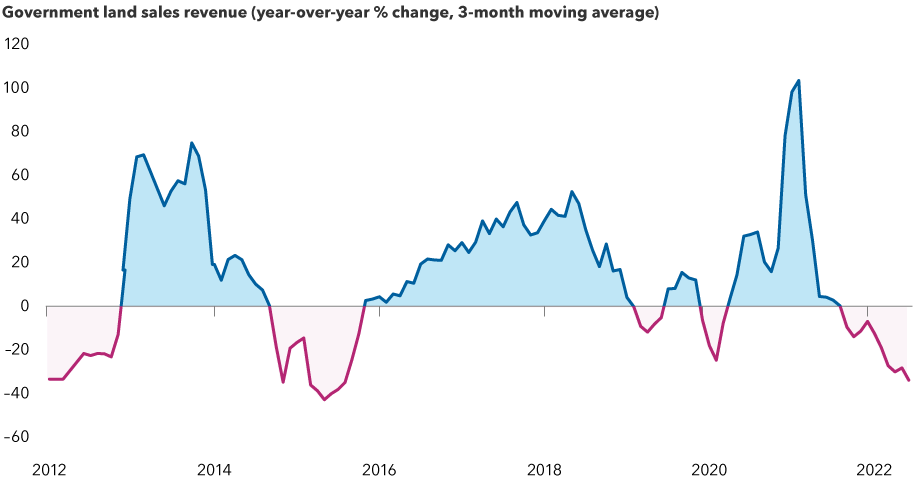

There’s been speculation that more fiscal stimulus is coming. This might come from Beijing, allowing local governments to sell more specialized bonds. But I don’t think infrastructure spending will accelerate much — based on my numbers, it hasn’t yet. Partly, that’s because governments don’t have the funds. Land sales have fallen sharply, declining close to 30% year over year amid woes in the property sector, hurting tax revenues and local government finances.

And that is having an impact on the amount of funds Beijing has for its much-vaunted infrastructure stimulus. I believe bond issues from local governments have mostly been used to cover the gap left by declining land sales and to pay interest on already-large outstanding debts, rather than toward infrastructure projects.

Beijing will need to get a lot more aggressive in its bond issuance to move the dial on infrastructure, in my view. This remains a possibility if, as I currently believe, the extent of the downturn becomes clearer.

Revenue from land sales has tumbled

Source: CEIC. Data reflects three-month moving average. Figures as of June 1, 2022.

5. Common Prosperity remains a top priority

The government’s Common Prosperity agenda, which aims for more equitable income distribution, remains a top economic priority for the next five to 10 years. While no details have emerged, this could change the trajectory of the economy and investment opportunities. It likely means higher corporate taxes and additional household taxes, such as property, consumption and inheritance taxes. Raising taxes, though, is difficult everywhere in the world, so the default option would be to put more pressure on companies to “do their bit” and make contributions to Common Prosperity projects. Investors would undoubtedly prefer the transparency of taxes.

Also, the Communist Party has expressed its desire for its domestic economy to be self-reliant and self-sufficient in key technological areas, such as automation, semiconductors and electric vehicles.

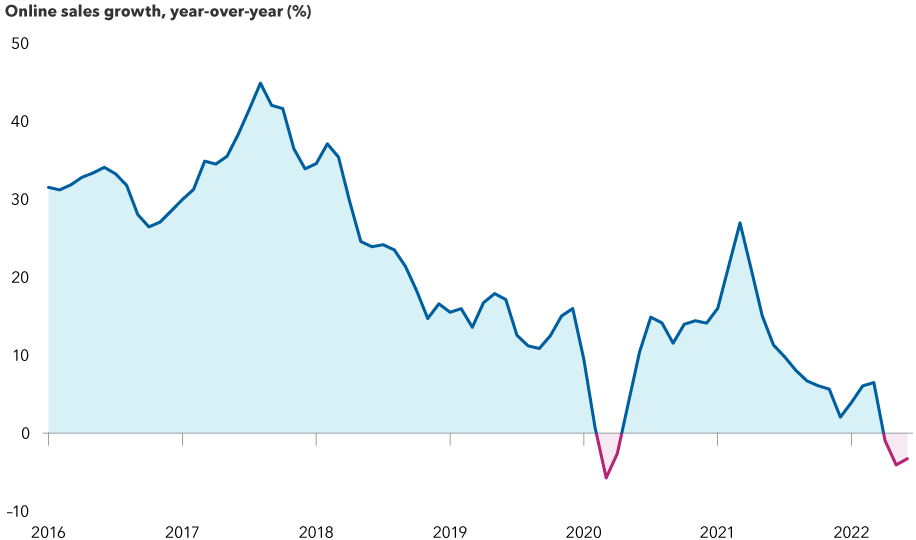

In the near term, I believe the key decision-makers are comfortable with sacrificing a great deal of growth to achieve their strategic priorities, including the prevention of what party officials have called the “disorderly expansion of capital.” As part of this broad effort, government leaders have reined in the country’s technology sector after a decade of impressive growth and innovation. This has included fines and controlling the information released to investors, dismantling the private-education sector and limiting the amount of time minors can spend playing online video games.

Beijing this past spring expressed its support for the country’s digital economy, and there have been encouraging signs on the regulatory front that the worst could be over for China’s technology giants.

For example, after a yearlong probe, ride-hailing firm Didi Chuxing was recently fined more than $1 billion by regulators over breaches of the country’s data security laws. The fine followed similar large fines imposed on Alibaba and Meituan. Regulators also cleared dozens of video games for release for the first time since July 2021. These developments could help shore up stability in the embattled internet platform sector. Furthermore, valuations for many Chinese equities have come down sharply over the past year and may already reflect this regulatory risk.

Online sales have weakened

Source: CEIC. Data reflects three-month moving average. Data as of June 1, 2022.

Bottom line

I don’t expect a short-term recovery in China’s economy before the vitally important 20th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) this fall, when President Xi Jinping is widely expected to secure a third term as CCP general secretary and the top 250 or so posts within the party are determined. Following this, in March 2023, government posts — and most importantly the State Council and premiere — will be announced.

I believe the market is too sanguine about the macro risks China currently faces. I could be wrong, of course. But until there is a fundamental shift in Beijing’s dynamic zero-COVID policy or a super-bazooka fiscal stimulus, I’m sticking to my view and expect China’s equity markets to remain volatile.

Stephen Green

Stephen Green