Chart in Focus

Demographics & Culture

You might think where you buy your coffee in the morning doesn’t amount to a hill of beans when it comes to the health of the U.S. economy. But, in fact, it could mean a great deal in the years ahead.

“Working remotely for the past year and a half, I’ve been buying coffee closer to home instead of my usual downtown coffee shop,” says Capital Group economist Jared Franz. “In my case, it doesn’t mean much, but if a quarter of the U.S. labor force does it one or two days a week, it has significant implications for the economy, financial markets and the future of large cities.”

While the data is short term and the jury is still out, there are early signs of a powerful deurbanization trend in the United States and other major developed economies. Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, migration from some big cities has accelerated while suburban home prices have soared. Moreover, national labor force surveys indicate an overwhelming majority of employees who have been working from home want to continue doing so one or more days per week.

Moving out: 2020 urban exodus

Sources: U.S. Department of Commerce, Visa Business and Economic Insights. Net migration includes movers from abroad. As of December 31, 2020.

By 2022, Franz estimates, roughly 25% of U.S. employees could be working remotely — up from just 5% prior to the pandemic — and many of them will choose to live in less expensive, less crowded areas. Assuming this shift persists, it would be the biggest change in labor force patterns since World War II.

“From an investment perspective, we need to determine how durable these changes are, how they could affect consumer spending patterns and how companies may respond,” Franz explains. “For instance, what happens to that downtown coffee shop? Or the restaurants that serve the same area? Or the office space that is no longer needed?”

“I don’t think we are talking about the death of big cities, by any means,” Franz stresses. “But I do think we may have reached peak density for urban centers such as Chicago, Los Angeles, New York and San Francisco. They will have to adapt to a world where much of the labor force is no longer coming into an office every day. Twenty-five percent may not sound like much, but it’s a huge change from 5%.”

Many important questions remain unanswered: Will people flock back to big cities after the pandemic is over? Will they prefer life in the suburbs and other outlying areas? Or will both happen at the same time — perhaps with younger employees preferring to live in vibrant, dynamic cities and older workers continuing to fuel the growth of the suburbs and exurbs?

One crucial question appears to be resolved: People like working from home.

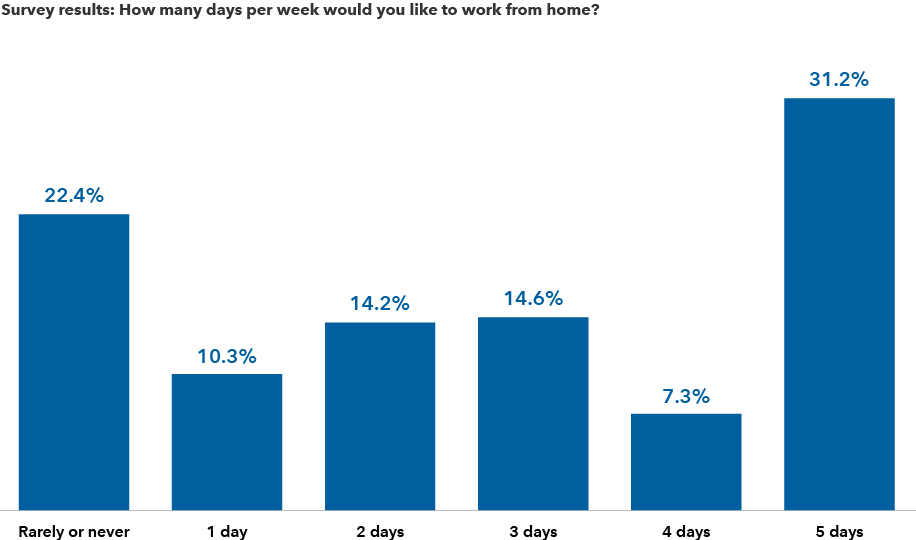

Want to work from home? Yes please!

Source: National Bureau of Economic Research working paper, “Why working from home will stick.” Based on surveys of 33,250 respondents conducted from May 2020 through March 2021. Results include all respondents who said they can work from home at least part of the time and those who reported mainly working from home at some point during the COVID-19 pandemic, which was 64% of the full sample.

Surveys by the National Bureau of Economic Research show that employees who are able to work from home definitely want to continue doing so. More than 77% said they would like to work remotely at least one day per week and 31% said they would prefer all five days. Not every job can be done remotely, of course, but 64% of respondents said their jobs are conducive to working from home at least part of the time.

It’s important to note that not everyone is on board with the work-from-home phenomenon. There has been a quiet backlash in recent months from certain companies pushing for more traditional work schedules, as well as the possibility of lowering the pay of employees who move from high-cost cities to lower cost areas. Companies don’t appear to be gaining much traction on those issues at the moment.

One large investment bank recently posed the question of whether we have reached the end of the honeymoon phase of remote work, citing concerns about employees’ isolation and mental health, the loss of company culture, the fate of downtown businesses and the growing threat of cyber attacks.

Sectors that benefit from deurbanization

Many sectors stand to benefit if the deurbanization trend endures, including personal travel and leisure, technology and communications, cloud computing, and the home improvement industry and residential real estate — particularly in the suburbs and other outlying areas.

Changes in consumer behavior mean these trends could be durable even as we head back to the office several days a week. For example, stores such as Home Depot and Lowe’s have clearly benefited from more people buying new and existing homes in the suburbs while the shift toward home fitness has boosted companies such as Peloton and Nike.

Exercise and outdoor activities are a potential bright spot, says Capital Group portfolio manager Lisa Thompson. “As an investment theme, I think it’s almost metaphoric. People are spending more time in nature, hiking or riding bikes, and they are realizing it’s actually very nice to be outdoors, to spend more time with family, to visit the national parks. I have friends who go camping now I never imagined would go camping.”

Sectors that suffer from deurbanization

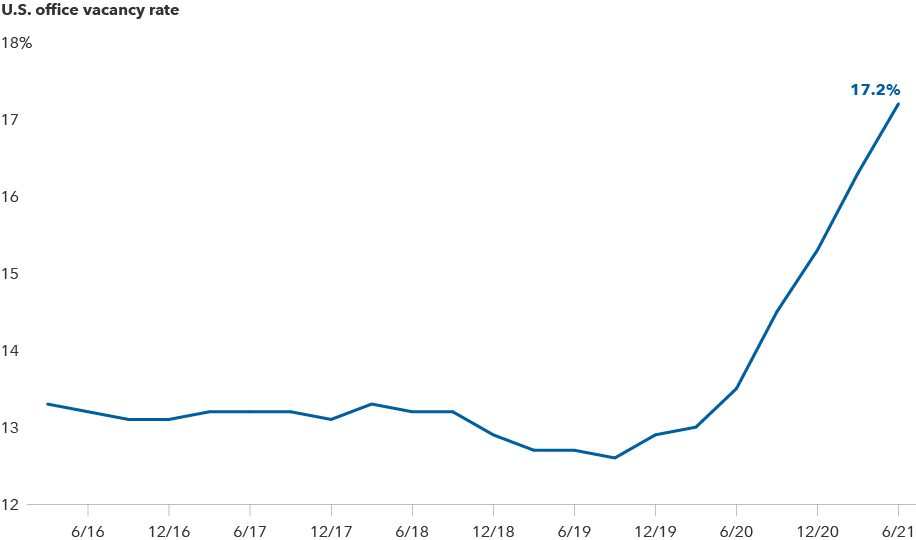

On the flip side, commercial real estate stands out as one of the hardest hit sectors, and the outlook remains challenging to say the least. Office vacancy rates nationally rose above 17% in the second quarter of 2021, up from roughly 13% in the first quarter of 2020 before government-imposed lockdowns brought the economy to a virtual standstill.

Commercial real estate has been hit hard

Source: Cushman & Wakefield. As of June 30, 2021.

Commercial real estate loans, meanwhile, have not experienced the type of distress or outright defaults that investors might expect, largely due to government stimulus programs that helped small and mid-size companies meet their lease and payroll obligations. “We’re in a holding pattern right now because government support has been so strong,” Franz notes, “but as we move into 2022, I think that could change materially for the worse.”

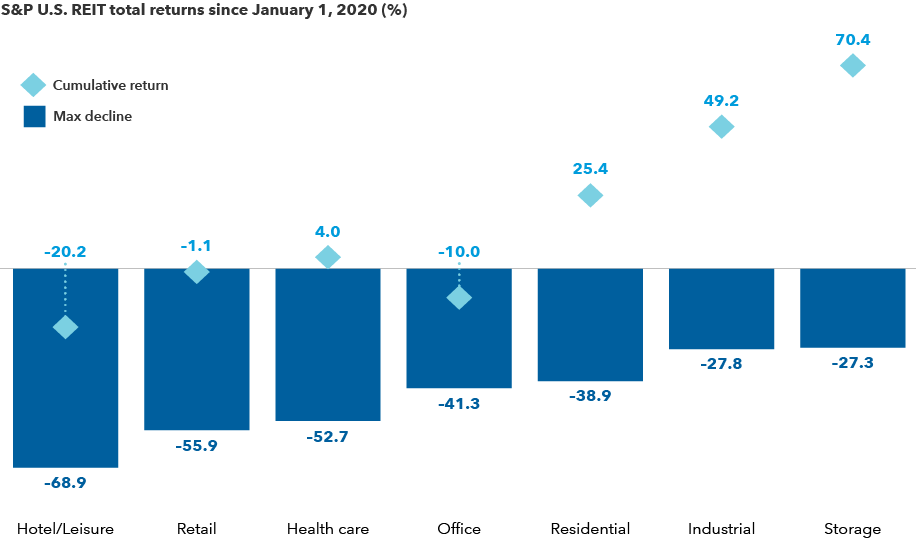

Within the wider real estate industry there has been a large disparity between subsectors that have been hammered — office, retail and hotel, for instance — and others that have rallied as the economy and stock markets recovered from the downturn. Those include storage, industrial and residential categories.

A tale of two real estate markets

Sources: Refinitiv Datastream, Standard & Poor's. As of 9/10/2021. Represents total returns of subsectors within the S&P U.S. REIT Index.

In states with large urban centers, state and local government finances could also be impacted, Thompson adds.

“Deurbanization puts a lot of pressure on states like New York and California that have relied on a very high tax base of wealthy people in Manhattan, Los Angeles and San Francisco,” Thompson notes. “It could wind up being a big challenge for states that have benefited enormously from the mega-city concept.”

Echoing Franz’s sentiment, however, Thompson says she expects large urban centers to adapt and eventually thrive in a post-COVID environment. Big cities are resilient, she says, and they have a long history of recovering from difficult times.

“I can remember when big cities were not places that people wanted to go in the 1970s and 1980s,” Thompson recalls. “Today, older people may say, ‘I don’t need to be in the city anymore,’ but I think younger people will still want to be at the center of civic life and entertainment. Cities will just reinvent themselves again.”

The S&P United States REIT Index defines and measures the investable universe of publicly traded real estate investment trusts domiciled in the United States.

Standard & Poor’s 500 Composite Index (“Index”) is a product of S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC and/or its affiliates and has been licensed for use by Capital Group. Copyright © 2021 S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, a division of S&P Global, and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved. Redistribution or reproduction in whole or in part is prohibited without written permission of S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC.

This report, and any product, index or fund referred to herein, is not sponsored, endorsed or promoted in any way by J.P. Morgan or any of its affiliates who provide no warranties whatsoever, express or implied, and shall have no liability to any prospective investor, in connection with this report. J.P. Morgan disclaimer: https://www.jpmm.com/research/disclosures.

Investing outside the United States involves risks, such as currency fluctuations, periods of illiquidity and price volatility. These risks may be heightened in connection with investments in developing countries.

Jared Franz

Jared Franz

Lisa Thompson

Lisa Thompson