Market Volatility

Market Volatility

- The current bull market run has been remarkably tranquil, but it’s important to condition clients to the fact that a correction could come at any time.

- Positioning portfolios to endure potential setbacks has historically been far more effective than making abrupt moves following some kind of market action.

- Our research shows that equities have tended to gain a majority of the time in most market cycles, and providing this perspective (along with setting aside cash for immediate short-term expenses) may be helpful in keeping clients invested even during tough times.

One of the most noteworthy elements of the current bull market has been its remarkable tranquility. Currently in its ninth year, this advance has been marked by extremely low volatility with very few selloffs. Still, history tells us that even the most vibrant rallies eventually give way to selling pressure, either temporary corrections or more damaging bear markets. As you know, it is impossible to predict when a correction will set in — or when a correction might deepen into a full-fledged bear.

Nevertheless, it’s helpful to understand the nature of past downturns to assist in your conversations with clients. To shed greater light on this subject, our researchers analyzed the length and severity of past market drops. Though the precise causes often vary from one selloff to another, we found that there are two fundamental types of declines: major pullbacks, which often correspond with recessions, and shorter-lived downturns that occur in the course of longer lasting rallies.

In the postwar period, the S&P 500 has dropped 15% or more on 16 occasions. Half of those were relatively mild, lasting less than eight months. Nearly one-third of the time, the index was at a new high within 10 months of the previous peak. As for major pullbacks, the median duration was 17 months, with a drop of more than 30%. Again, these declines are typically associated with recessions. Thus, gauging the potential depth of a market decline involves trying to determine the stage of the economic cycle. Currently, our research suggests the U.S. economy is not exhibiting any of the obvious excesses or imbalances that historically have foreshadowed economic contractions.

It’s important to note that equity valuations have not tended to be reliable predictors of market weakness. In fact, valuations have remained elevated for extended periods without a significant drop in stock prices. There have even been “bull market contractions” in which the P/E ratio actually fell as prices advanced because underlying earnings rose even faster.

You and your clients should avoid the urge to time the market

Regardless of market conditions, there is a natural human instinct to make portfolio adjustments based on what one thinks will happen. As you know, this impulse isn’t confined to periods when stock prices are falling — it’s equally tempting when stocks are rising. Just as some clients are inclined to reduce equity exposure following a market decline, others are reluctant to maintain stock investments during a rising market because they worry that a correction might occur.

Our analysis demonstrates that abrupt moves can be costly. Research indicates that it’s not only impossible to predict short-term market moves, but that retreating from stocks at the wrong time can significantly damage long-term returns. For example, the S&P 500 had an average annual return of 7.7% from 1997 to 2016. But an investor who missed just the best 40 days during that span would have suffered a 2.4% annual loss.

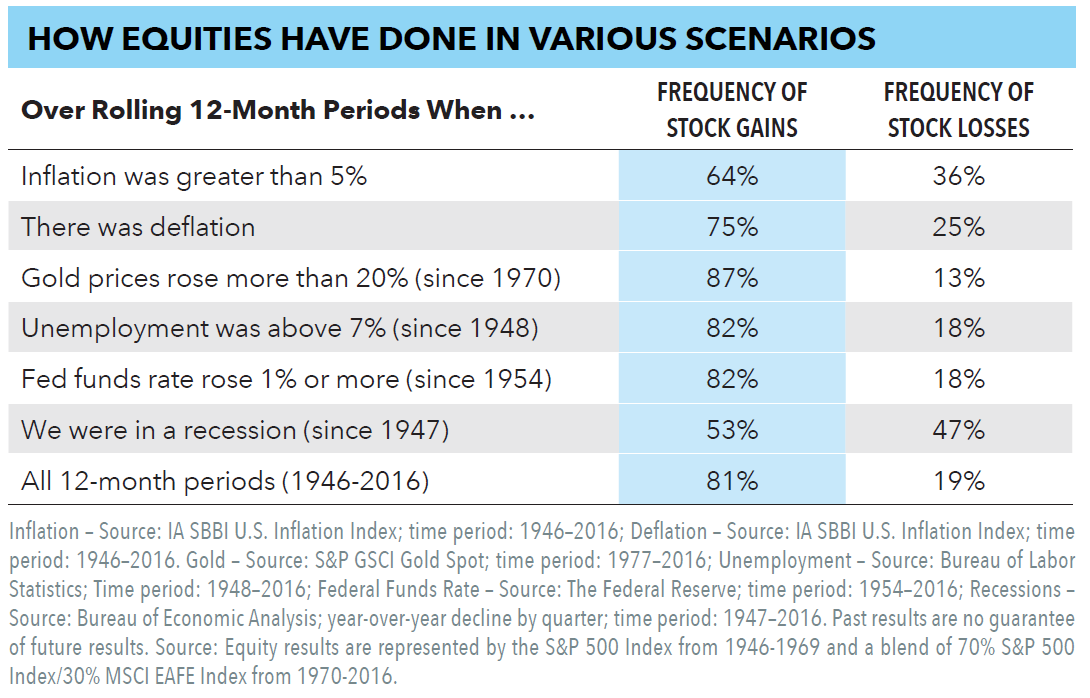

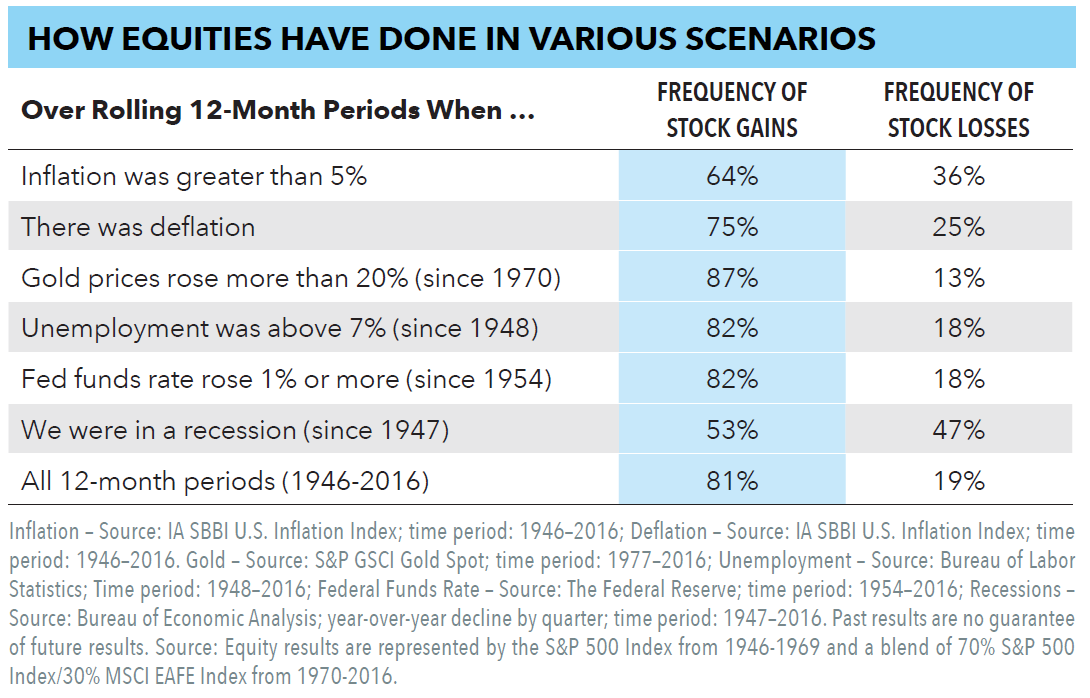

Our analytics team studied a range of postwar environments to gauge whether economic signals were a reliable precursor to market declines. In other words, they looked at whether it was possible to time the market based on economic red flags. Going back to 1946, we found that stocks appreciated in 81% of all rolling 12-month periods, including both weak and strong environments. We looked exclusively at challenging times, such as when inflation was high, gold prices were surging or unemployment was elevated. Surprisingly, we found that equity markets delivered overwhelmingly positive returns even during these tumultuous periods. Only recessions seemed to have a reliably dampening effect on stocks, but avoiding those periods would have required advance warning. Unfortunately, even the most highly regarded economists are notorious for their conflicting — and often incorrect — views about when recessions will materialize.

There are two suggestions to consider in trying to help prepare clients for a market correction.

First, think about setting aside one to two years of living expenses in short-term, liquid assets such as high-quality short-term bonds. Though this is significantly higher than the typical three-to-six month “emergency cash fund” suggested in basic financial planning courses, this approach not only provides any necessary liquidity to meet short-term liabilities, it also helps provide clients with the emotional wherewithal to withstand the inherent volatility of their longer term investments. Given that the average peak-to-recovery duration for pullbacks of 10% or more is approximately 21 months since 1926, setting aside this amount seems reasonable. Where we have implemented this with clients, it has helped prevent them from making knee-jerk reactions to their strategic asset allocation in periods of increased volatility.

Second, consider the objectives of the investment strategies for your client, not just the asset class or style box. In addition to where a portfolio invests, objectives such as capital appreciation, income, capital preservation or a combination of these allow a reasonable tolerance around asset-class targets that provides portfolio managers with a measured degree of flexibility. This drives a significant part of the client experience, and the results are particularly meaningful in a market correction. Do your clients have the right mix of investment objectives in their portfolios? For clients who are especially sensitive to equity declines, consider a growth and income strategy, which typically exhibits less volatility and lower downside capture than those focused on capital appreciation.

Of course, none of this inoculates the market from a sudden or sharp decline. Exogenous shocks such as geopolitical events and policy miscues can spark pullbacks. I believe the best strategy is to establish a thoughtful portfolio structure based on each client’s time horizon, risk tolerance, risk capacity and personal financial goals. This approach helps clients stick with their portfolio objectives through the inevitable gyrations in the market. And as the chart above illustrates, the market has been up far more often than it has been down, meaning odds are that moving to the sidelines would ultimately be a costly experience.

RELATED INSIGHTS

-

Guide to recessions: 9 key things you need to know

-

Market Volatility

Guide to stock market recoveries -

Artificial Intelligence

Separating AI hype from investment opportunity

Statements attributed to an individual represent the opinions of that individual as of the date published and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of Capital Group or its affiliates. This information is intended to highlight issues and should not be considered advice, an endorsement or a recommendation.

Use of this website is intended for U.S. residents only.

Michelle J. Black

Michelle J. Black