Chart in Focus

Inflation

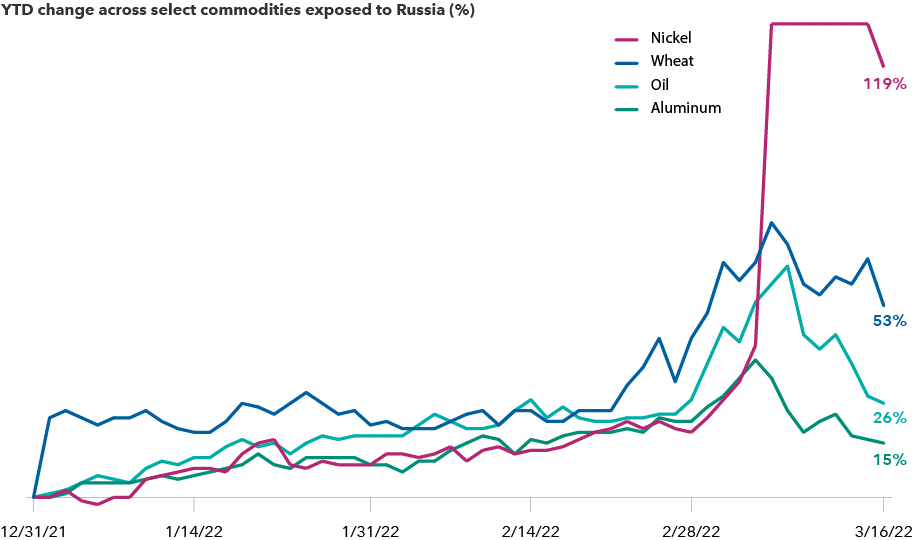

For a glimpse of just how volatile commodities currently are, look at nickel markets. Prices doubled in early March. Then they fell sharply. Then the London Metals Exchange halted trading. This week, the market for nickel — a key component in electric vehicle batteries and stainless steel products — reopened but with strict trading limits.

It’s just one example of how the global economy is being disrupted by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Russia provides about 20% of the world’s nickel supply. The threat of losing it roiled trading markets and sent buyers scrambling for other sources.

Commodity prices skyrocket amid the Russia-Ukraine conflict

Sources: Capital Group, London Metal Exchange, Refinitiv Datastream, U.S. Department of Agriculture. As of March 16, 2022.

Commodity prices have climbed sharply since the February 24 invasion, especially for materials produced in Russia and Ukraine. That includes wheat, oil and natural gas, as well as other key metals such as aluminum, palladium and copper.

But prices were rising long before the start of the conflict, contributing to inflationary pressures not seen since the early 1980s. So, the crucial question for investors is: Are these price spikes sustainable?

“In the short term, the answer is no,” says Lisa Thompson, a portfolio manager with New World Fund®, “The market has overreacted, and we’re already seeing prices come back down a bit. But, compared to where we were a year ago, commodity prices are significantly higher — and I do think that’s a durable trend.”

“Over the long term,” Thompson adds, “prices are likely to remain elevated due to a number of factors, including rising demand, supply shortages and deglobalization forces symbolized by the war in Ukraine and strained U.S.-China relations. Higher prices should be expected in a world where free and open trade is in retreat.”

Metals industry poised to shine

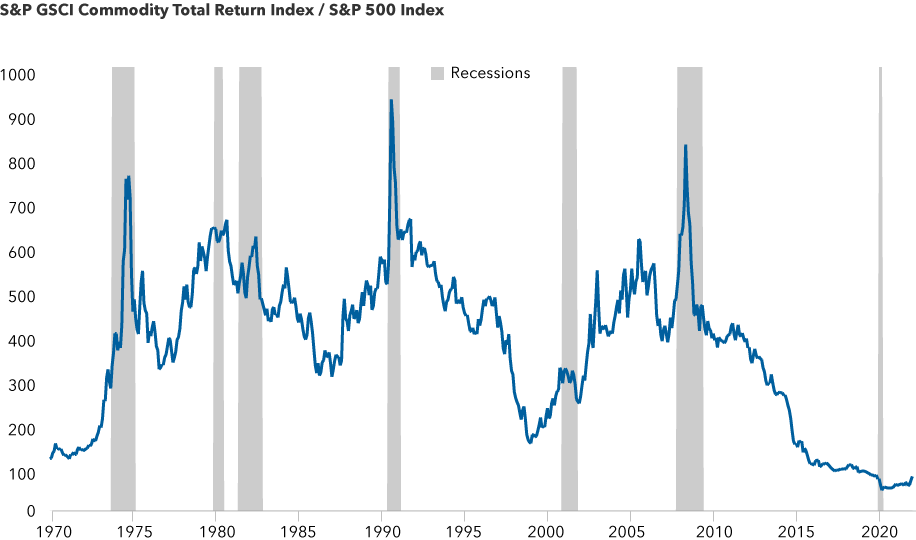

From an investment perspective, this has clear implications for the metals & mining sector. It has been a neglected area of the market for more than a decade — even longer if you exclude the last major price spike during the 2008 global financial crisis.

The sector has been undervalued for years and remains so today despite a recent rally in mining company stocks, says Douglas Upton, a Capital Group equity analyst who has covered commodity markets for more than 30 years. Upton thinks many commodity prices will remain high for years due to chronic underinvestment by the industry since 2015. The problem is exacerbated by the fact that it takes more time than it did in the past to launch new mining projects.

“It’s a multiyear process,” Upton explains. “Discovery, permitting and funding all take much longer. In price terms, that points to higher highs and higher lows until new investments start to produce results.” This dynamic doesn’t apply to food and other crops, Upton notes, because production in those areas can be ramped up much faster.

Historically speaking, commodities are cheap relative to U.S. stocks

Sources: Capital Group, Refinitiv Datastream, Standard & Poor's. The price ratio between the S&P GSCI Total Return Index and the Standard & Poor’s 500 Composite Index is scaled to 100. Data shown from 2/27/70 to 2/28/22.

“All of the big mining companies are undervalued in my view,” he says. “The market is not thinking enough about the consequences of the underinvestment theme. Valuations, and consensus earnings estimates, assume that commodity prices will decline over the next few years, closer to historical averages. I think that is quite wrong.”

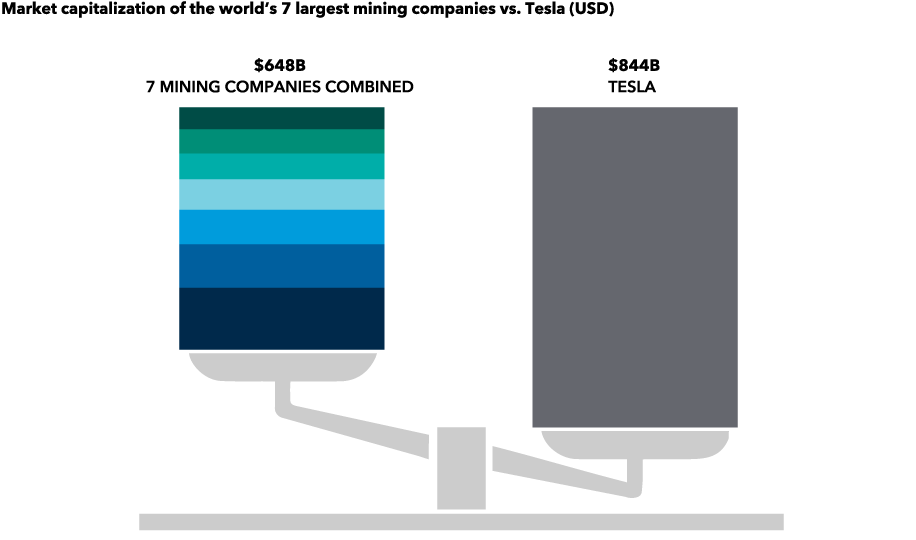

Case in point: Look at the market capitalization of the world’s seven largest mining companies. Even combined, they do not come close to the market value of a beloved new-economy company such as Tesla. The automaker needs certain refined metals, including nickel, to produce its lithium-ion batters. So much so that Tesla CEO Elon Musk cited access to nickel as one of his biggest production concerns long before Russia invaded Ukraine.

Mining companies toil in obscurity despite key role in global economy

Source: RIMES. As of 3/16/22. Mining companies represented (from largest to smallest) include BHP, Rio Tinto, Vale, Glencore, Freeport, Anglo American and Newmont.

In addition to underinvestment, another factor that could lead to higher commodity prices over the long term is the worldwide push for sustainable energy sources, Upton adds. Electricity, in particular, has become a favored resource. The expansion of the power grid — along with the rapid adoption of electric vehicles — will require lots of copper, nickel and other key metals.

China: A counterbalance to rising prices?

On the flip side, China’s slowing economy could act as a counterbalance to keep commodity prices in check. As the largest importer of raw materials, China consumes more than half the world’s iron ore, coal and copper supplies. When China’s economy slumps, the global commodities complex tends to sputter.

China’s close trading relationship with the European Union could also expose it to a wartime recession in Europe if the war in Ukraine drags on. Moreover, China is dealing with a COVID-19 resurgence that could further hamper the economy as the government renews restrictions on travel and entertainment.

“Even before the latest COVID outbreak, China’s economy was decelerating or at least stabilizing at a very low rate of growth,” says Stephen Green, a Capital Group economist who covers Asia. “Things are likely to get worse before they get better, and a sufficiently bad recession could cause commodity prices to fall.”

China’s central bank will probably cut interest rates soon, Green notes, while most other central banks around the world are moving in the opposite direction.

Investment implications: Inflation hedge

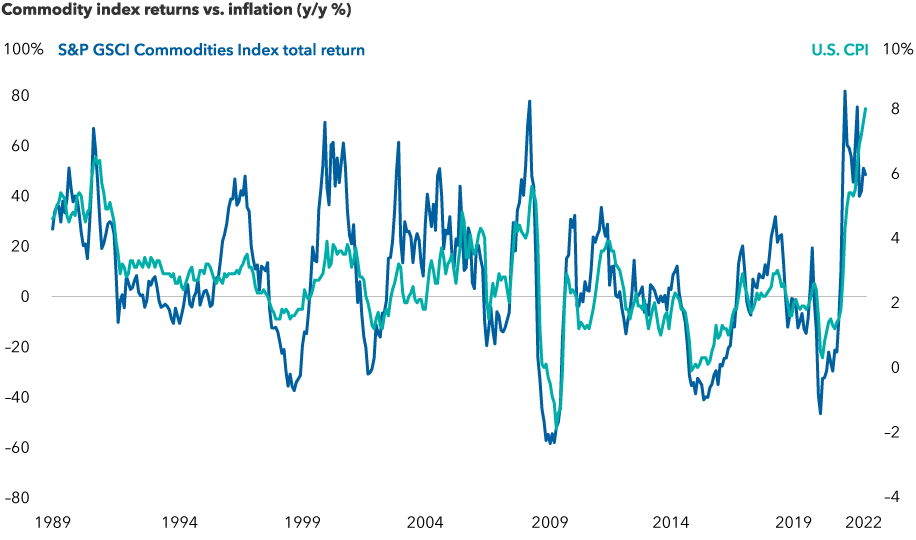

Regardless of where markets go from here, the current price surge confirms, once again, that commodities are an effective hedge against inflation. That’s not surprising since those very commodities — oil and gas, for instance — feed into many aspects of the global economy and can help to fuel inflation, which is currently running at a 40-year high.

Historically speaking, energy — especially oil — has moved closely in line with inflation, as measured by the U.S. Consumer Price Index. Since oil is usually a major component of commodity-related indexes, the long-term correlation between commodity prices and inflation is high.

No surprise: Commodities are an excellent hedge against inflation

Sources: Capital Group, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Refinitiv Datastream, Standard & Poor's, U.S. Department of Labor. Data shown from 1/31/89 to 2/28/22.

However, it’s also important to note that there are big differences between major categories of commodities. Oil and gas, metals, food and agricultural products often follow their own cycles.

Investors seeking an inflation hedge should keep that in mind, says Capital Group economist Jared Franz. “It all depends on the source of the inflation,” he notes.

“Unsurprisingly, the energy sector tends to do well when inflation is rising because energy price increases, especially for gasoline, can be quickly passed on to consumers,” Franz says. “That’s not always the case with other commodities, where price increases can be absorbed as they move through the production chain.”

Investing outside the United States involves risks, such as currency fluctuations, periods of illiquidity and price volatility. These risks may be heightened in connection with investments in developing countries.

The market indexes are unmanaged and, therefore, have no expenses. Investors cannot invest directly in an index.

The U.S. Consumer Price Index (CPI) is a measure of the average change over time in the prices paid by urban consumers for a market basket of consumer goods and services.

The S&P GSCI Commodity Total Return Index is an index of commodity sector returns representing an unleveraged, long-only investment in commodity futures broadly diversified across the spectrum of commodities.

Standard & Poor’s 500 Composite Index is a market capitalization-weighted index based on the results of approximately 500 widely held common stocks.

Standard & Poor’s 500 Composite Index (“Index”) is a product of S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC and/or its affiliates and has been licensed for use by Capital Group. Copyright © 2022 S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, a division of S&P Global, and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved. Redistribution or reproduction in whole or in part is prohibited without written permission of S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC.

Lisa Thompson

Lisa Thompson

Douglas Upton

Douglas Upton

Stephen Green

Stephen Green