Chart in Focus

Inflation

- The Federal Reserve’s willingness to tolerate higher inflation may keep policy loose for an extended period.

- Accommodative policy and a weak labor market are likely to keep bond yields low.

- Inflation risk is skewed to the upside over the longer term.

- This risk underscores the need for inflation protection in portfolios.

In January, the Federal Reserve affirmed its commitment to low interest rates for a prolonged period of time under its new monetary policy framework. If anything, with its renewed focus on “broad-based and inclusive” maximum employment and a goal of achieving inflation that averages 2% over time, the Fed has made the conditions for policy removal more stringent. Speaking after the meeting, Chair Jerome Powell stressed the importance of “substantial further progress” toward the employment and inflation goals before the Fed would consider adjusting its policy stance.

Here’s my current thinking on inflation expectations and where Treasury yields could head in the near and medium term, as well as how investors should think about a strategic allocation to inflation protection.

Temporary bumps in inflation may occur

Consumer prices have recovered from recent lows as economic restrictions have been lifted. Still, they remain below pre-COVID levels. Looking ahead, I expect that core PCE (Personal Consumption Expenditures, the Fed’s preferred inflation gauge) will accelerate temporarily above 2% in the spring of 2021 but will likely decelerate toward the end of the year as low inflation data from 2020 rolls off. Similarly, the economy may experience temporary bumps in inflation as it reopens.

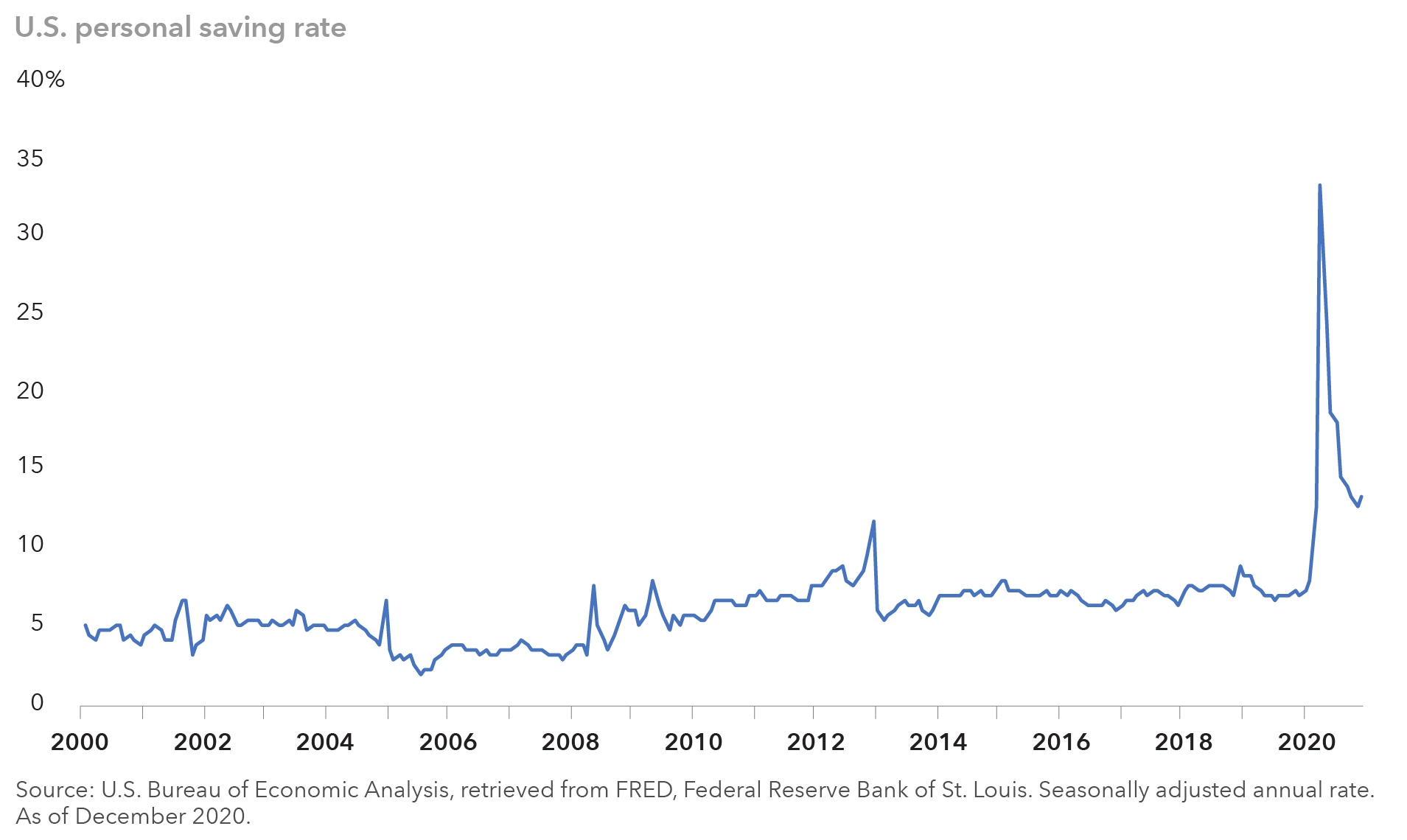

Many households shored up their savings over the past year, and we could see a release of pent-up demand and consumers re-engaging in select services. However, that impulse is unlikely to last unless there is a sustained and robust economic recovery.

Elevated household savings could fuel a burst of spending

Accommodative policy and a weak labor market are likely to keep bond yields low

The economic growth outlook continues to improve with the rollout of COVID-19 vaccines and another round of fiscal stimulus. Still, Fed policy is likely to remain accommodative for a long time, keeping bond yields well-anchored in the lower range. There are a few reasons for this:

More “reactive” policy. As part of its year-long framework review, the Fed adopted a monetary policy prescription that it said will be more “reactive” and less “proactive” regarding economic outcomes. In recent speeches, Powell has deemphasized the Fed’s reliance on models such as the Phillips curve in guiding policy decisions, due to the uncertain and imprecise cause-and-effect relationships underlying them. (The Phillips curve is an economic concept stating that inflation and unemployment have a stable and inverse relationship.) Furthermore, Powell stresses the importance of seeing desired economic outcomes materialize before making policy changes. One lesson from the previous rate cycle was that the Fed’s dependence on such models led it to hike rates far too soon in fear of inflation that never materialized. It raised rates by 200 basis points over two years starting in December 2016, then had to readjust policy by cutting rates three times in 2019.

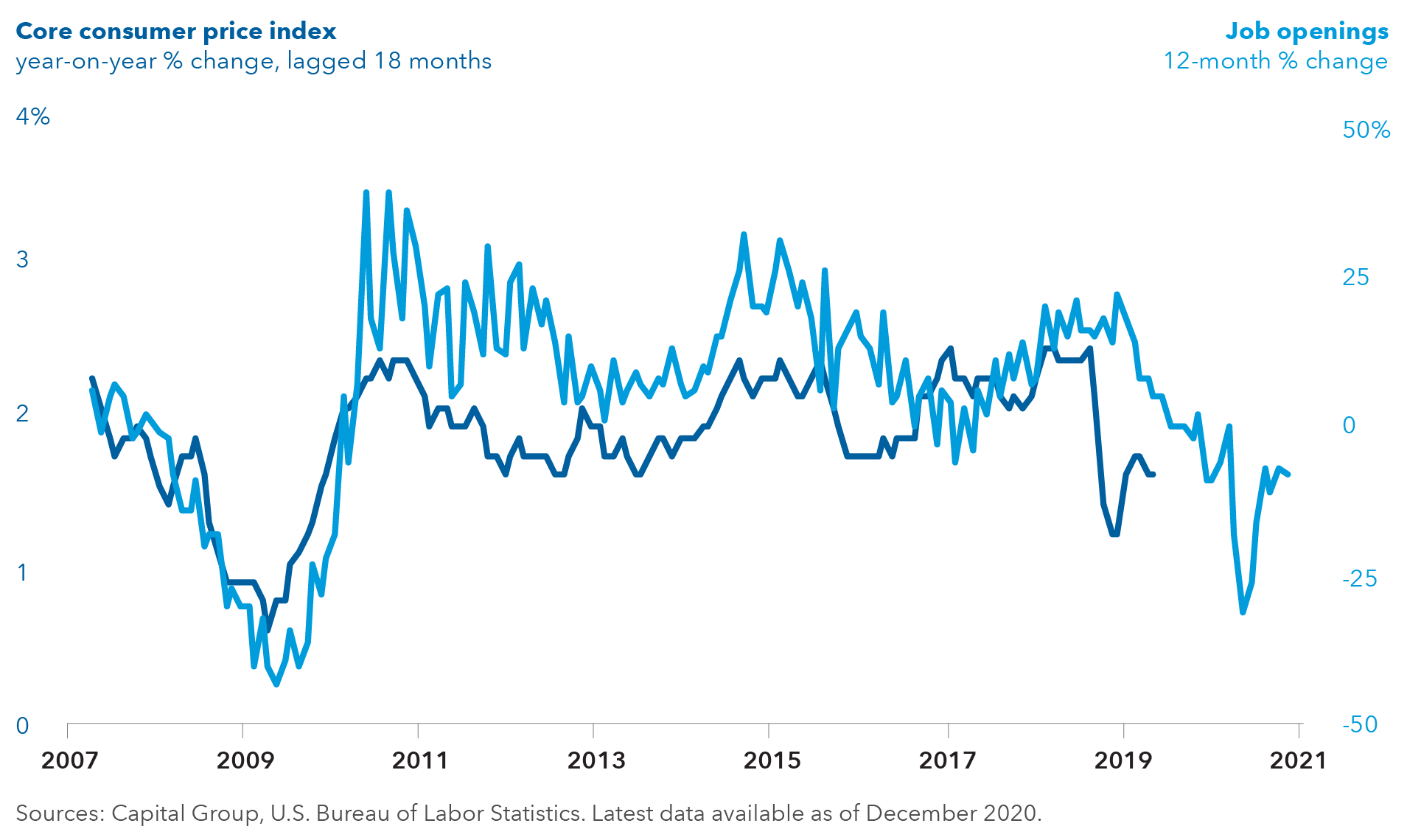

Slow recovery in the labor market. The labor market has been slow to heal and is unlikely to meet the Fed’s newly adopted definition of “broad-based and inclusive” maximum employment anytime soon. Recently, the Fed strengthened its employment mandate as part of its policy framework review, putting it ahead of its inflation goal and emphasizing that policy decisions will aim to address only “shortfalls” in the employment goal.

So far, the evidence suggests a long road ahead. January’s unemployment rate remained elevated at 6.3% while the employment-to-population ratio was 57.5%, near the lowest levels since the early 1980s. Improvements in initial and continuing jobless claims appear to have plateaued. Moreover, these measures mask the wide disparity in labor metrics across demographics and income groups, hiding the level of slack in the labor market.

Inflation likely to stay muted with a slow labor market recovery

New measures to gauge employment. At the January meeting, Powell said the Fed will look beyond traditional measures of labor markets such as the U3 unemployment rate, which simply reflects unemployed persons who are actively looking for work, and will now include indicators such as the employment-to-population ratio, participation rates and labor characteristics across different demographic groups. He also highlighted the Fed’s focus on racial inequalities in the labor market, emphasizing that an inclusive recovery has long-term benefits to the productive capacity and potential output of the U.S. economy.

The Fed’s focus on average inflation. The Fed has become increasingly concerned about falling inflation expectations and the risk of getting into a Japan-style low-inflation, low-rate trap. Powell hopes to address these concerns by committing to low policy rates until inflation averages 2%. This means the Fed will likely tolerate higher levels of inflation for a while before considering lifting rates. Furthermore, at the January rate-setting meeting, Powell cautioned against making policy changes in response to what will likely be “transient” jumps in inflation rates in the coming months from base effects (distortions resulting from last year’s low inflation) and the impact of the economy reopening.

Inflation risk is skewed to the upside in the long run

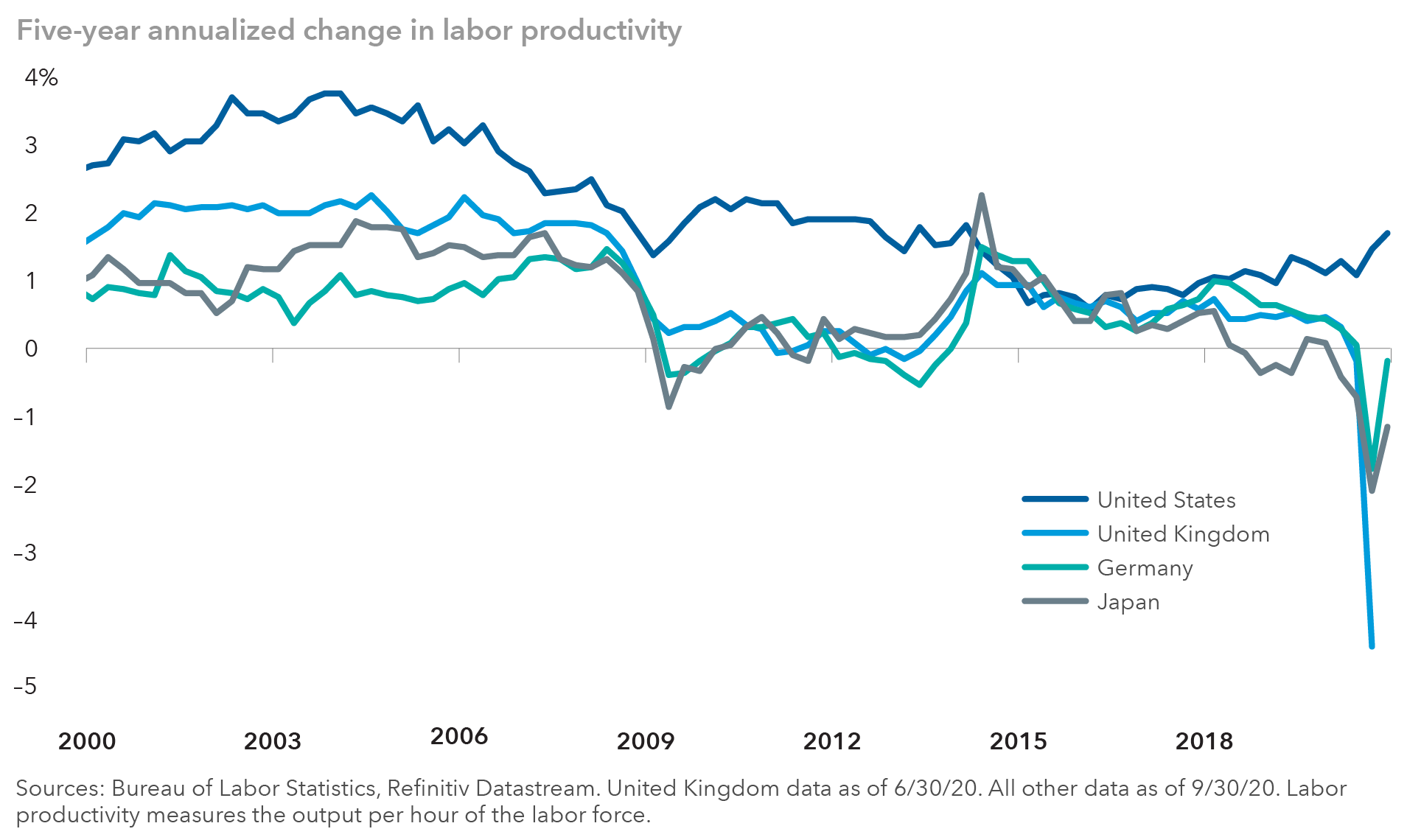

Structural factors can push prices in both directions, leading to a more uncertain outlook for inflation. On the one hand, deglobalization, populist trade policies, large fiscal deficits and easy monetary policies should push inflation higher in the coming years. On the other, large and persistent output gaps and technology-led productivity gains should act as a drag on inflation. The concentration of wealth in the upper strata of society, which has a lower propensity to consume than middle and lower-middle classes, also has a deflationary effect. The impact of aging demographics and rising global debt levels on inflation is less clear.

Rising labor productivity is a deflationary force. The U.S. leads on this front.

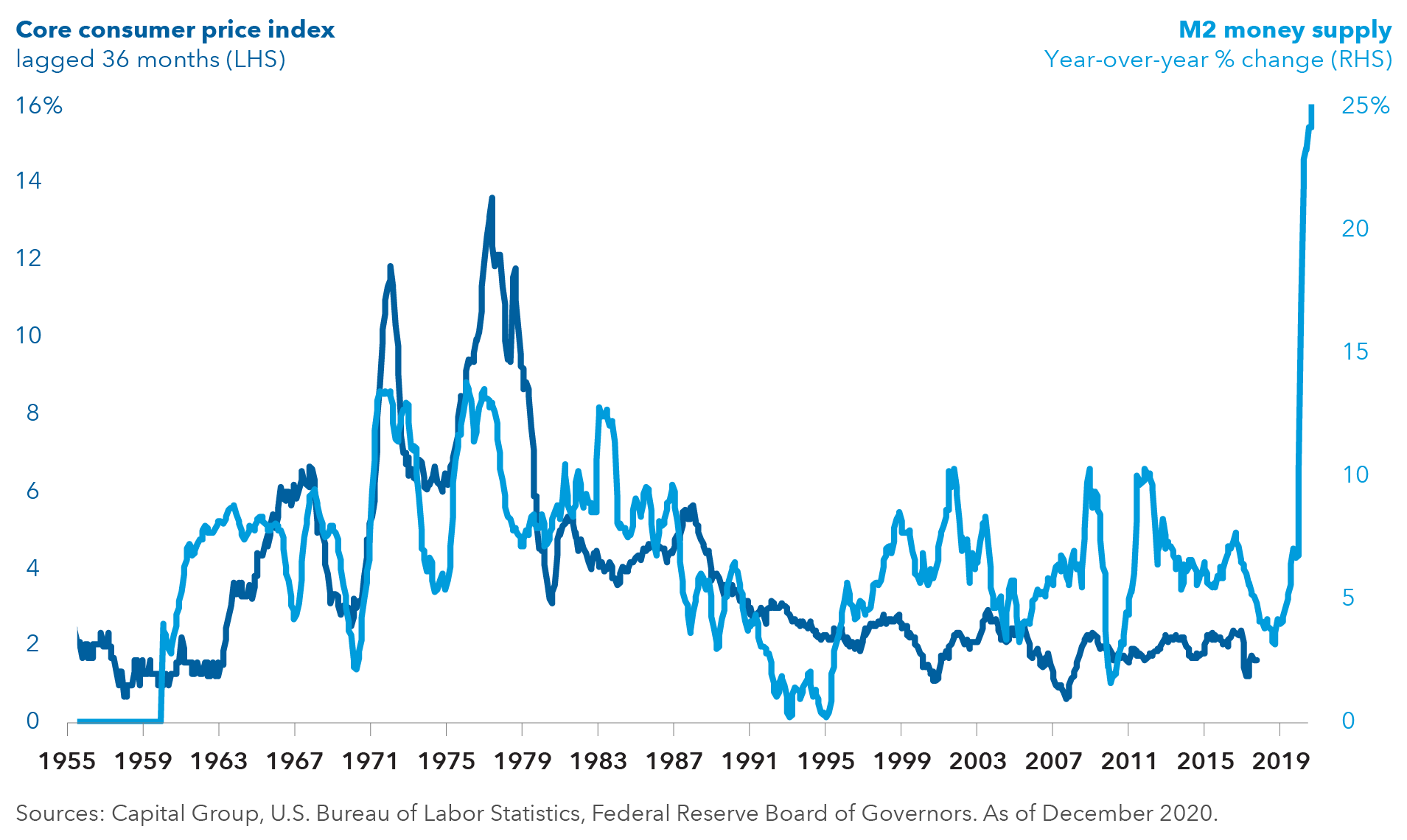

That said, I believe that over the longer term, the risk of inflation appears skewed to the upside. Policy makers seem complacent about the prospect of higher inflation simply because prices have been relatively benign in recent cycles. Fed officials have repeatedly said they are not worried about inflation and view low inflation as the more immediate threat. As a result, the unprecedented fiscal and monetary expansion being deployed is leading to rapid growth of the money supply and credit. In the past, rapid growth of the money supply has coincided with meaningfully higher inflation rates, such as in the period spanning the 1970s.

In the 1970s, a sharp increase in money supply contributed to high inflation

Investment implications

What does this mean for interest rates and inflation protection? There is room for bond yields to rise modestly from their current historically low levels. However, I think the 10-year Treasury will remain below the pre-pandemic level of around 2% this year, anchored by low Fed policy rates.

Although yields are low, U.S. Treasuries can still serve as a buffer against an adverse move in risk assets, and they offer more attractive yields than their global peers. Investors have bid up most risk assets in this environment of ultra-accommodative monetary policy and low interest rates, driving equity price-earnings multiples to multi-year highs.

Given the Fed’s rising tolerance for higher inflation, adding inflation protection securities seems prudent. The central bank is more likely to be reactive to inflation outcomes than proactive. Moreover, the surge in money supply and fiscal deficits in major economies has raised concerns about future excess demand. We believe these factors may contribute to a secular rise in realized inflation and nominal yields over the long term. Investments such as Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS) appear to be good hedges against this type of policy error.

Capital’s interest rates team has favored investing in TIPS within broad fixed income portfolios. We also like investing in bonds and currencies with high correlation to commodity prices to enhance our inflation protection.

As an offset, we have maintained duration positions in our strategies that are somewhat shorter than their respective benchmarks in anticipation of a modest rise in Treasury yields, and are also positioned for a flatter yield curve. We believe this provides some balance of risks within our portfolios. If inflation proves stubbornly low for longer, we believe the yield curve could flatten as the Fed would likely expand its accommodative policy.

RELATED INSIGHTS

-

-

-

Client Conversations

Timothy Ng

Timothy Ng