Economic Indicators

Markets & Economy

A great deal of market commentary over the past several months has focused on the potential for the U.S. economy to achieve a “soft landing.” What exactly is that?

A soft landing essentially describes an economy that slows enough to allow inflation to fall, but not so much that it tips into a recession. It is an achievement that many investors doubted could occur two years ago when the Federal Reserve first launched its fight against inflation.

Even I thought the window of opportunity was narrow. However, since then, inflation has come down, job creation has cooled but remains positive, and the U.S. economy has avoided a recession. The inflation battle isn’t over, as it remains above the Fed’s 2% target. However, it is close enough that Fed Chair Jerome Powell all but promised a rate cut during his highly anticipated speech in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, last week.

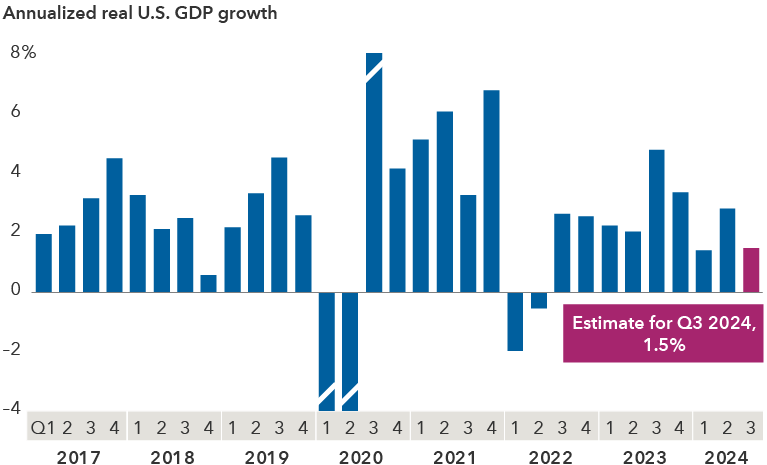

A resilient U.S. economy has decelerated but hasn’t stalled

Sources: Capital Group, Bureau of Economic Analysis, FactSet. Figures for Q1:20, Q2:20, and Q3:20 are –5.5%, –31.6%, and 31.0% respectively, and are cut off by the y-axis given the extreme fluctuations associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. Estimate for Q3:24 is based on the mean consensus estimate from FactSet. As of August 22, 2024.

If the Fed does so at its September meeting, it will be the first rate cut since the COVID-induced recession in March 2020, and it will mark the end of the Fed’s historic two-year monetary tightening campaign that began in March 2022.

What comes next?

Although there is no official definition of a soft landing, it is considered for the purposes of this analysis to occur when real GDP growth expands, on average, for three quarters at a pace below the economy’s potential growth rate (currently 2.0% per the Congressional Budget Office’s estimate) with none of those quarters showing an outright contraction. If the U.S. economy grows at a 1.5% annualized rate in the third quarter of 2024 — the current consensus estimate — it will have met this definition of a soft landing.

This could be an important milestone because, when it has occurred historically, the economy has tended to accelerate in subsequent periods. This pattern could repeat in 2025, especially if the Fed lowers rates.

U.S. economic growth has accelerated after past soft landings

Sources: Capital Group, Bureau of Economic Analysis. Chart includes all periods identified as a soft landing since 1950. Soft landing defined as periods with less than 3% (pre-2006) or 2% (post-2006) average growth over a three-quarter period with no negative quarters. Data shown is a three-quarter moving average of the annual percent change in real gross domestic product (GDP). As of August 26, 2024.

Party like it’s 1995?

If the economy does land softly in the current quarter, it could bear some similarities to the end of another aggressive Fed tightening cycle in early 1995 that concluded with the federal funds rate at 6.0%. Despite that rapid increase, the economy expanded robustly until 2000, weathering multiple financial difficulties along the way, including the Mexican peso crisis, the Thai baht devaluation, the Russian default and the collapse of hedge fund Long-Term Capital Management.

During that period, the Fed made modest adjustments to the federal funds rate: It was cut by 75 basis points, raised by 25 basis points, cut again by 75 basis points and then raised by 175 basis points to end the cycle at 6.5%, all while core inflation remained at or below the Fed’s 2.0% target. If a similar path were followed today, we could see a cycle-low federal funds rate of 4.125% and an end-of-cycle rate of 5.875%.

That said, in 1995 the U.S. economy had more slack than it does now, with an unemployment rate of 5.5% (eventually falling to 3.8%). The unemployment rate currently stands at 4.3%, so there could be less room for a long expansion. In addition, it is possible that the same level of interest rates today exerts a greater drag on the economy than it did then because of higher debt levels and demographic changes.

Conversely, factors that could mitigate the drag from higher interest rates include fiscal stimulus, structural reshoring and capital expenditures related to artificial intelligence.

So far, however, the economy does appear to be tolerating higher interest rates. Despite recent concerns, the labor market seems to be holding up as well. A recent increase in the unemployment rate occurred as the economy created 114,000 new jobs, which indicates that the increase was driven primarily by additions to the labor force. This is precisely what Fed officials would like to see and most likely what they would consider a soft landing — slack being introduced in the labor market in a manner that allows wage growth to moderate while employment is still increasing.

Of course, if the influx to the labor force slows and the economy reaccelerates in 2025, the unemployment rate could start to decline again.

Interest rate outlook: Temper your expectations

Based on activity in the interest rate futures market, investors expect the Fed to cut rates by 50 to 75 basis points by the end of this year, and more than 100 basis points in 2025. I think there is a reasonable probability that we get less than that.

Market expectations for Fed rate cuts may be too ambitious

Sources: Capital Group, Chicago Mercantile Exchange, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, National Bureau of Economic Research. Upper bound of target range is used since 2008. Actual data and market expectations as of August 23, 2024.

After a few rate cuts, if the U.S. economy continues to grow — or even accelerates, per past soft landings — and job growth remains healthy, I am not sure the Fed would want to risk overheating an economy that appears to be in reasonably good shape. That would be especially true if inflation remains stuck in a range above 2%, as Powell suggested was possible in his remarks last week.

Whenever Powell speaks it is like a Rorschach test. People hear what they want to hear and see what they want to see, and I am likely no different. With that caveat, I do not see the Fed cutting rates as aggressively as the market expects. That said, I am on record predicting that the Fed was unlikely to cut rates at all in 2024, so unless there is some very surprising economic data in the next two weeks, my prediction will be off by a few months. However, we will still likely end 2024 with substantially fewer cuts than the market was expecting at the start of the year.

Early next year, if we are looking at a U.S. economy that is expanding above its potential growth rate — boosted by one or two rate cuts — the Fed might declare mission accomplished and leave it at that. Putting monetary policy on cruise control for a while could make sense, given the importance of price stability following the worst inflation spike in 40 years.

Even with fewer cuts than expected, this environment could still be supportive for stocks and bonds. A growing economy should provide a tailwind for equity prices over the long term, while rates could remain at a level that presents bond investors with a real alternative to equities.

Hear more from Darrell Spence:

RELATED INSIGHTS

-

-

Market Volatility

-

Darrell Spence

Darrell Spence