Client Relationship & Service

Practice Management

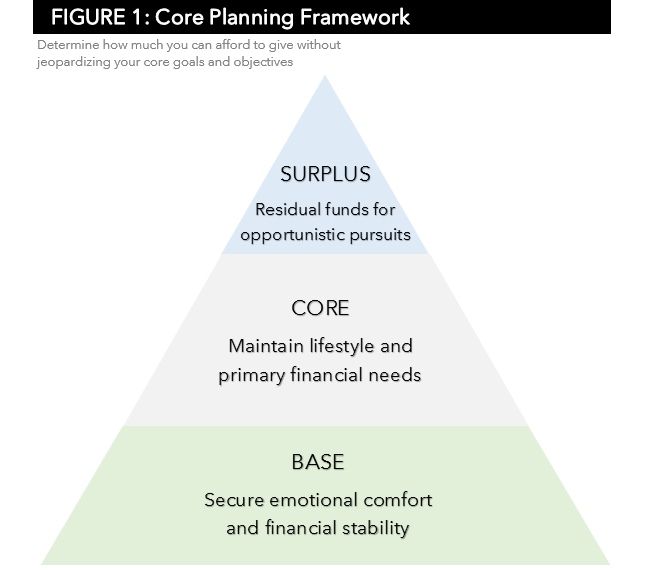

- It’s important to quantify how much clients can afford to give away without jeopardizing their other financial objectives.

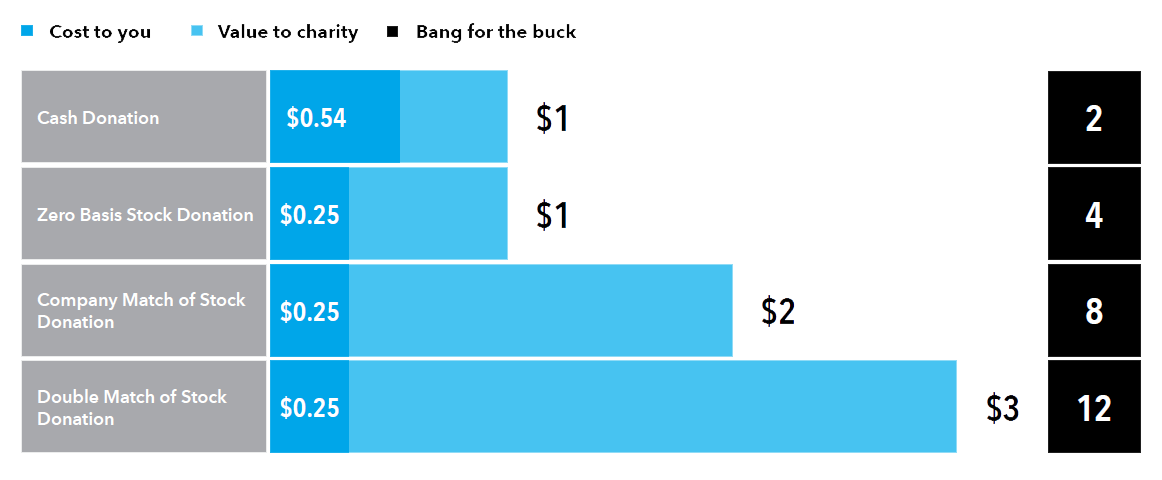

- Donating low-cost-basis stock doubles the benefit over donating cash.

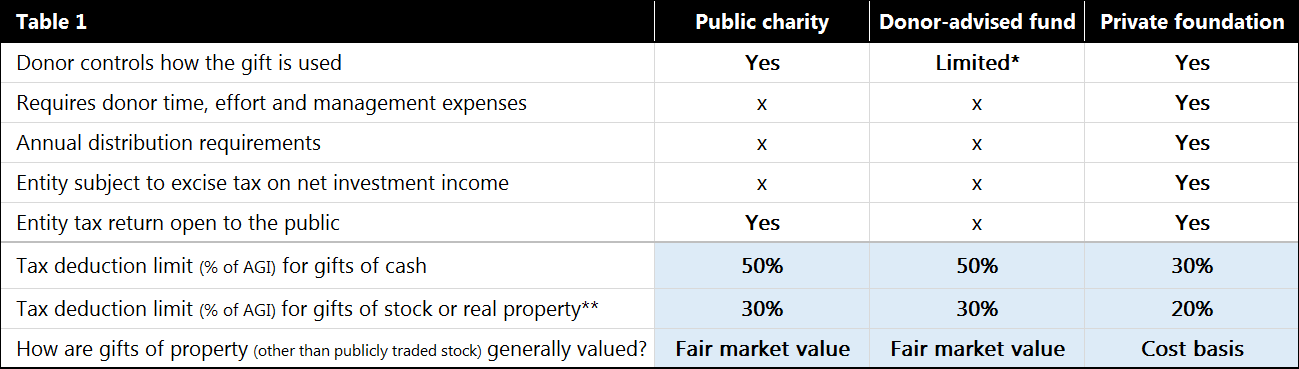

- The decision between setting up a private foundation versus a donor-advised fund comes down to tax implications, simplicity and how involved donors want to be.

A common question among high net worth investors is how to be financially strategic when donating to charity. In other words, what’s the best way to maximize philanthropic giving while minimizing the tax impact? As a wealth advisor, you can provide a lot of assistance in this area. Among other things, you can help clients determine how much they can afford to donate, which assets should be given and whether it’s advisable to support a public charity or establish a private family foundation.

To gauge how much a client can afford to give, I suggest using the planning pyramid shown below as a reference. It starts with a “base” portfolio of short-term investments to support near-term spending, followed by the “core,” or the amount of money needed to endow a lifestyle based on conservative return assumptions that take into account poor markets and a long life. Any additional money, which we refer to as “surplus” capital, represents the gifting capacity available for either family or philanthropic pursuits.

As for which assets to gift and which vehicles to leverage, first consider income tax rates. The top federal tax bracket for individuals is 39.6%. Further, the top federal tax rates on short-term and long-term capital gains could be as high as 43.4% and 23.8%, respectively, if the tax of 3.8% on net investment income is included. If state and local taxes are included, the combined tax rate for individuals could top 50%.

If we assume a 10% state and local tax rate, and that state and local taxes are fully deductible on a federal tax return, a blended rate of 45.6% is applied to top-bracket income. The chart below illustrates how the income tax deduction provides leverage to charitable gifting. On the top line, you can see the “cash donation.” For each $1 given, a client gets the 46% deduction noted above, so the net cost is just 54 cents. Put another way, if you divide the $1 benefit to charity by the 54 cents it cost the donor, there is a 2:1 “bang for the buck” in the black box.

If stock is donated, the taxpayer doesn’t have to pay the embedded capital gains tax. We see that benefit on the second line. If the stock that has zero cost basis, then the net cost is only 25 cents, and there is a 4:1 bang for the buck. If the client works for a company that offers a corporate match on charitable donations, the bang for the buck grows to 8:1. A double match can bring the ratio to 12:1.

Based on paying top marginal 2017 tax rates.

Reflects benefit of blended federal and state tax deductions. The blended tax rates assume that state taxes paid are claimed as an itemized deductions on the federal tax return. The formula for the blended tax rate is federal tax rate + (1 – federal tax rate) x state tax rate. We have assumed that the full amount of state taxes paid is deductible on the federal tax returns (i.e., the Pease Limitation does not apply). For purposes of this presentation, we have assumed the highest federal marginal income tax rate on ordinary income, short-term capital gains, and long-term capital gains. In addition, we have assumed all taxable income, including capital gains, is subject to a hypothetical state marginal income tax rate of 10 percent. Tax rates in this table are based on the rate in effect as of 2017

“Bang for the buck” is calculated as “value to charity” divided by “cost to you.” “Cost to you” compares the cost of selling the zero basis stock to the cost of donating it.

Here are two key rules of thumb: Donate low-cost-basis stocks and take advantage of corporate matches. These are straightforward and powerful guidelines.

Public charity or private?

There are three basic ways to carry out philanthropy: Donate directly to a public charity, set up a private foundation or use a donor-advised fund (DAF). Each has benefits and limitations, as outlined in the chart below. The choice largely rests on the tax implications, how involved donors want to be and how much time they can devote to the process.

In general, gifts to public charities (and DAFs) carry larger tax benefits than those made to foundations. When cash gifts are made to public charities, taxpayers can deduct up to 50% of their income. However, when donating stock, and/or when contributing to a private foundation, the limit might be 20% to 30% of income. Those who want to make a large charitable gift, or who are retired with lower income, might not be able to take full advantage of these deductions. However, qualifying taxpayers may be able to carry forward the excess contributions for up to five years to potentially lower future tax burdens.

The tradeoffs involved in private foundations and donor-advised funds

By creating a private foundation or contributing to a DAF, a taxpayer may be able to accelerate the tax deduction while deciding which charities to support. This can be particularly helpful in a high tax year resulting from the sale of a low-cost-basis stock position or from a stock-option exercise. The taxpayer can create a charitable fund in that year and deduct up to 50% of their income if they’re eligible. Thus, a taxpayer can accelerate the timing of the deduction, offset the sale of low-basis assets on which capital gains tax may otherwise be owed, and take full advantage of a charitable deduction that would get phased out in future lower-income years because of deduction limits.

A key benefit of a private foundation is the donor can maintain hands-on control, including oversight of investments and selection of recipients. This can be important if the donor is creating a personal charitable vehicle, such as supporting an organization with direct community involvement. It also is a way to build a legacy of philanthropy by engaging family members in a foundation’s mission and board meetings. Remember, however, that setting up a foundation can involve significant up-front and ongoing costs, as well as strict IRS oversight. In addition, all activities are publicly disclosed. In general, foundations are required to pay annual excise taxes of 1% to 2% of net investment income, and must distribute at least 5% of net investment assets each year. Thus, foundations generally require financial commitments of several million dollars.

A comparison of charitable vehicles

*A donor recommends the charitable recipient for a distribution, but it is up to the administrator of the donor-advised fund to approve the recipient.

**Percentages provided are for gift of long-term capital gain property.

By contrast, DAFs are easy to set up and relatively inexpensive to maintain. A benefactor can recommend a gift from the fund to an established 501(c)(3) organization, and the fund will make the gift on their behalf after verifying that it’s to a legitimate organization. There’s also no minimum annual distribution requirement. However, donors have less control over how the entities are managed and how the funds are doled out.

Cash contributions to charities can be deducted up to a maximum of 50% of adjusted gross income (AGI); for a foundation, the limit is 30%. Thus, a donor with an AGI of $500,000 could deduct as much as $250,000 for cash allocated to qualifying organizations, compared with $150,000 for money allocated to a foundation. For publicly traded stock or real assets given to a charity, the maximum deduction is 30% of AGI; for a foundation, it’s 20%.

There is also a difference in valuation treatment of property other than publicly traded equities, such as real estate or stock in a closely held company. Assume that a property purchased for $50,000 has doubled in value, to $100,000. If the property were donated to a public charity, the taxpayer would be eligible for a deduction based on the full fair market value of $100,000. But if the property were transferred to a private foundation, the deduction would be limited to the original cost basis of $50,000.

All else being equal, someone in this situation would likely be better off selling the investment and donating the cash proceeds to the charity because the deduction for the cash donation would more than offset the tax due on the sale. Assuming the donor is in the highest tax bracket, he or she would pay a long-term capital gains tax of $10,000 ($50,000 in appreciated value multiplied by a 20% tax rate) while qualifying for a deduction of $100,000.

Given the complexity of tax rules and the many considerations involved, you, along with your client’s legal and tax advisors, can provide essential advice that can help clients sort through their options, maximize their philanthropic impact and strengthen their relationship with you as an advisor.

RELATED INSIGHTS

-

-

Traits of Top Advisors

-

Practice Management

This material does not constitute legal or tax advice. Investors should consult with their legal or tax advisors.

Use of this website is intended for U.S. residents only.

Michelle Black

Michelle Black