Chart in Focus

Technology & Innovation

During a span of just 21 days in January, the rapid pace of change in the media and entertainment industry inspired three blockbuster deals.

Microsoft announced its intention to buy video game publisher Activision Blizzard for $75 billion — a transaction that aims to bring the iconic Call of Duty and World of Warcraft franchises under the tech giant’s umbrella. Take-Two Interactive unveiled its plan to shell out $12.7 billion for mobile game maker Zynga, best known for the FarmVille franchise. And Sony agreed to purchase Bungie, creator of the popular Halo and Destiny games, for $3.6 billion.

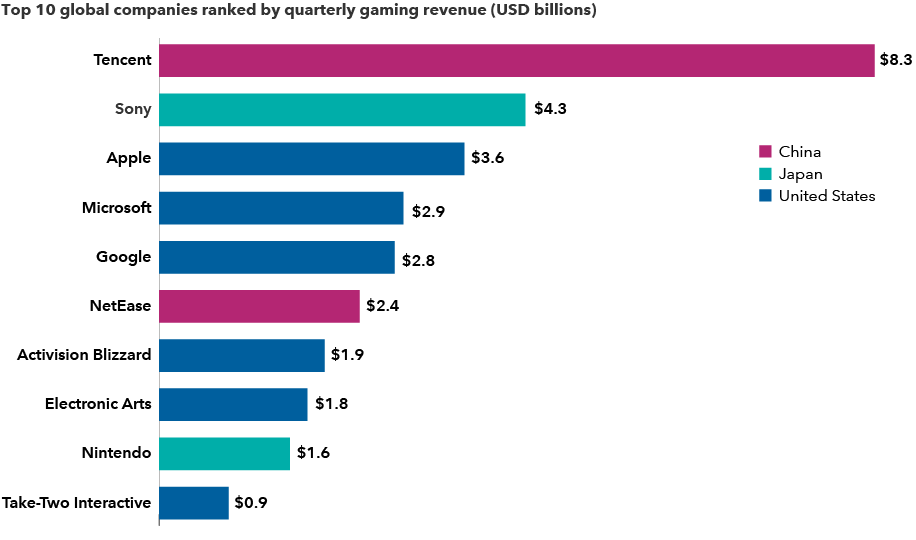

If all three deals close, that’s more than $90 billion of M&A activity centered on video games, the fastest growing segment of the media sector. The Activision deal is Microsoft’s largest acquisition ever and could vault it to the top of the $200 billion gaming industry, just behind China’s Tencent.

Gaming’s global appeal fuels industry leaders in Asia and the U.S.

Sources: Capital Group, Newzoo. Quarterly revenue figures are estimates by research firm Newzoo, as of September 30, 2021.

Driven in part by a pandemic-era gaming boom, the fast-changing media landscape is fundamentally transforming the way people interact and entertain themselves in a world where traditional TV viewing and movie attendance are in serious decline. That dynamic makes interactive games even more valuable to the likes of Microsoft, Sony and others.

“I think it’s a testament to how powerful and alluring video games have become,” says Martin Romo, a portfolio manager with The Growth Fund of America®. “The global gaming industry provides compelling entertainment at a reasonable cost, and it’s already surpassed the movie industry in terms of annual gross revenue. Fundamentally, I think that growth is likely to continue and even accelerate in the years ahead.”

Streaming and social media competition heat up

The disruption extends to other areas of the media world, as well.

“Another big theme playing out here is that you have a lot of companies trying to get into each other’s business,” says Jody Jonsson, a portfolio manager with New Perspective Fund®. “There was a time when they had these sandboxes all to themselves, but that’s changing. Everyone is looking at everyone else’s sandbox and trying to jump in.”

For example, Netflix — the clear leader in streaming video — is encountering fierce competition from Amazon and Apple, as well as old guard media companies such as Disney. In less than three years, Disney’s streaming service, Disney+, has grown to 130 million subscribers.

In the social media space, TikTok is challenging Facebook parent Meta Platforms, attracting hordes of young viewers thanks to the power of its short-form videos. Facebook has responded by launching its own short video offering, dubbed “Reels,” which is growing in popularity — just not as fast as TikTok, which was the most downloaded app of 2021.

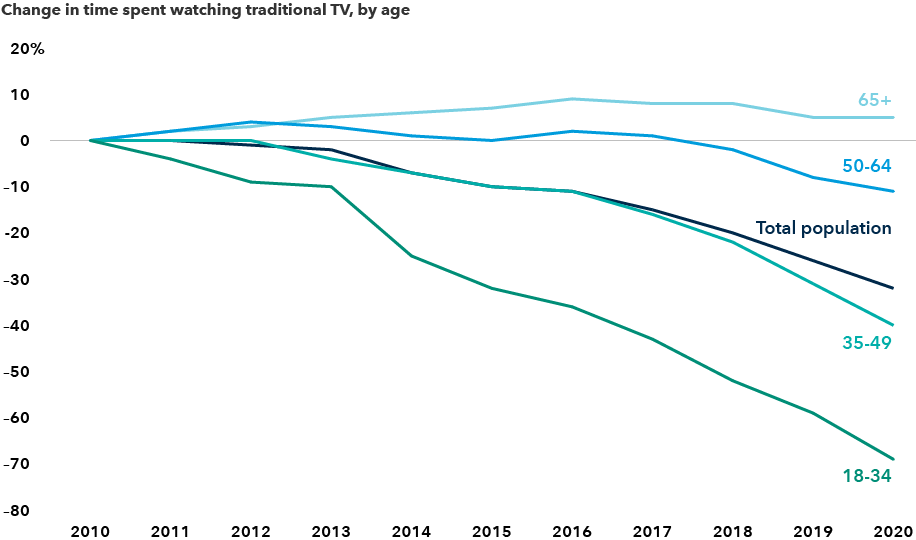

Other battles in the media business were lost years ago. For instance, a precipitous decline in traditional TV viewership — especially among young people — raises the possibility that once ubiquitous cable TV packages may no longer exist in a few years. If live sports and news programs ever move en masse to streaming services, that could spell the end of cable TV as we know it.

Young people are increasingly shunning pay TV

Sources: Capital Group, Nielsen. Traditional TV includes live TV and recordings of live TV (for example, using a DVR).

There’s no business like show business

This type of momentous change and disruption may appear surprising to some, but it’s par for the course in the media and entertainment biz, explains Capital Group equity analyst Brad Barrett, who has covered the industry for two decades.

“Media is always being roiled by technological change,” Barrett says. “It felt like a huge amount of change when the internet started disrupting traditional media outlets in the early 2000s. It felt huge when YouTube burst onto the scene. And then came social networking, smartphones and video streaming. They all caused a great deal of disruption and continue to do so.

“Don’t get me wrong, there’s certainly a lot going on right now,” Barrett adds, “but change and disruption are staples of the media business.”

One interesting new trend, Barrett notes, is the globalization of content production and consumption. Case in point: Three of Netflix’s most popular series — Squid Game, Lupin and Money Heist — film in South Korea, France and Spain, respectively. And they come with English subtitles, which had previously been a deterrent for many U.S. viewers. Not so anymore.

“Consumers around the world are watching content from all over the world in ways we’ve never seen before,” Barrett says. “It’s great to see English speakers embrace these non-English shows with such enthusiasm. I think it’s a very positive trend, and it’s a real breakthrough for global creativity.”

Metaverse now?

Looking ahead, what will be the next source of media disruption?

Based on the rising number of sensationalist headlines, the metaverse is certainly one candidate. Depending on who you ask, the much-touted metaverse is either the future of the internet or a virtual reality pipe dream.

As technologists have described it, the metaverse is an incredibly immersive and expansive digital world in which people can interact, transact, play games, attend concerts, watch movies, meet coworkers in a virtual office and engage in myriad other activities through user-created avatars.

The idea is so powerful it prompted Facebook to change its name four months ago to Meta Platforms, promising to transform the social media giant into a “metaverse company.” Meta will have plenty of competition, however. Microsoft declared the Activision deal is, in part, driven by a desire to develop compelling content for the metaverse — a world where virtual reality headsets may become as common as smartphones.

There are also many independent websites with a metaverse focus, including Sandbox, founded in 2012, and Decentraland, launched three years later. Users of these sites are already buying virtual land, virtual houses and virtual artwork, often with cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin, Ethereum, Cardano and Solana.

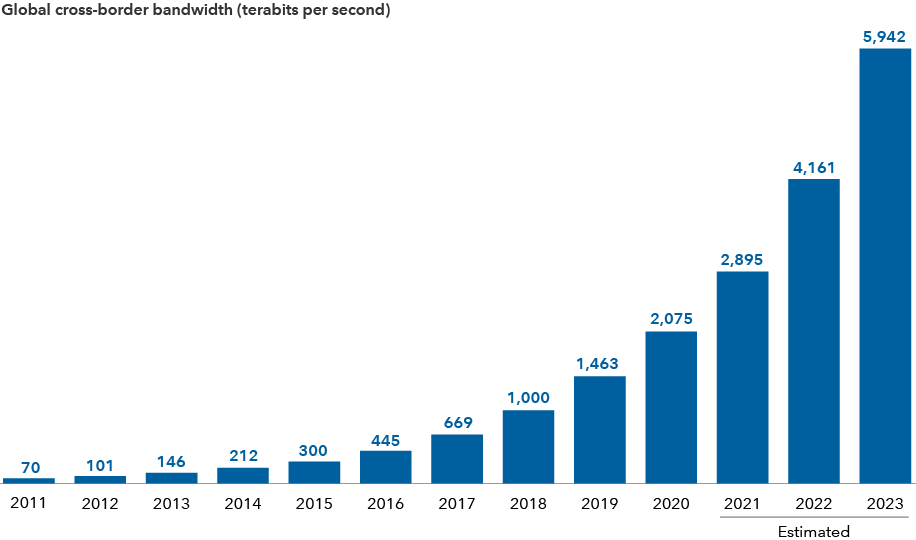

Bandwidth needs are expected to soar amid the growth of the metaverse

Sources: Capital Group, TeleGeography. Actual data through 2020. 2021 to 2023 are estimates.

Neal Stephenson originally coined the term metaverse in his 1992 novel Snow Crash. Ernest Cline further popularized the concept in his 2011 sci-fi novel Ready Player One, which subsequently became a movie. One oft-cited answer when people ask, “What is the metaverse?” is to read Ready Player One or at least watch the movie.

Clearly, the concept has been around a while and it’s not all hype, says Peter Eliot, a portfolio manager with SMALLCAP World Fund®.

“When I ask friends what they think of virtual reality, very few of them have tried it,” Eliot says. “That’s an excellent opportunity for us to leverage our long-term perspective and global research capability to try and understand and appreciate the metaverse now — in advance of what could be a substantial product cycle.

"Though nascent, the metaverse is further along than some might think," he adds. "For example, we’ve already experimented with meetings in VR — and we are thinking through scenarios for mass adoption and its broad investment implications.”

Investing outside the United States involves risks, such as currency fluctuations, periods of illiquidity and price volatility, as more fully described in the prospectus. These risks may be heightened in connection with investments in developing countries. Small-company stocks entail additional risks, and they can fluctuate in price more than larger company stocks.

Jody Jonsson

Jody Jonsson

Martin Romo

Martin Romo