Chart in Focus

Politics

Stop us if you’ve heard this one before: U.S. lawmakers are clashing over a legislative action to raise the federal debt ceiling. The issue has been percolating for months but could come to a head this summer as the U.S. Treasury starts running out of money to pay its bills.

The decision to increase the nation’s debt limit is often a routine one — except in years when Congress is divided, like it is now. With Republicans controlling the House of Representatives and Democrats in command of the Senate, the scene is set for what could be one of the most contentious debt ceiling showdowns in recent history.

So far, Democrats have said they won’t negotiate on the issue, while many Republicans have said they won’t vote to lift the debt limit without some additional agreements to curb federal spending.

“This could be the worst standoff we’ve ever witnessed,” says Capital Group political economist Matt Miller. “It certainly has the potential to be at least as bad as 2011.”

That’s the year Standard & Poor’s cut the United States’ prized AAA credit rating to AA-plus (where it remains) amid concerns about the government’s budget deficit, a growing long-term debt burden and political conflicts over raising the debt limit. The move unnerved U.S. financial markets for a time, but they quickly recovered.

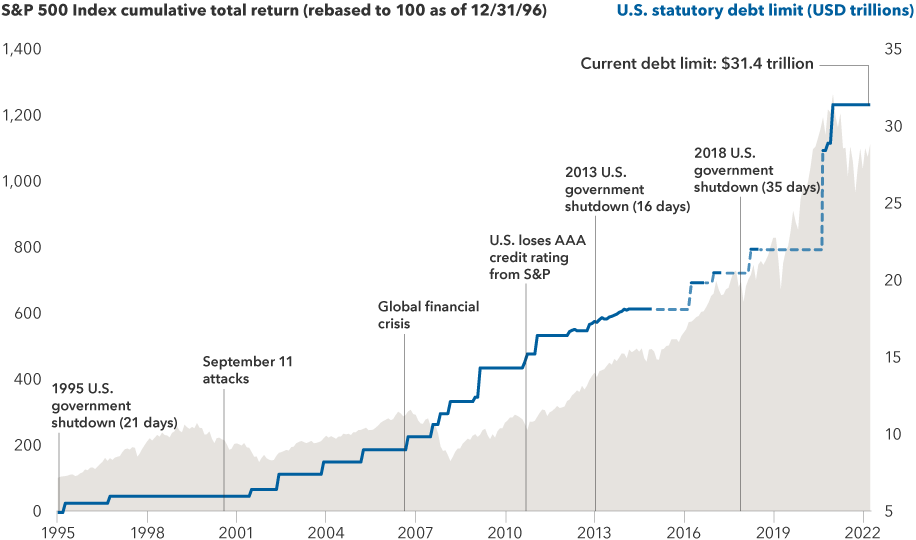

A debt ceiling standoff could get ugly, but markets have historically powered through

Sources: Capital Group, Refinitiv Datastream, Standard & Poor's, U.S. Department of the Treasury, U.S. Office of Management and Budget. Periods in which the statutory limit has been suspended are reflected by the dotted lines. These periods include February 4, 2013, through May 18, 2013; October 17, 2014, through March 31, 2017; September 30, 2017, through March 1, 2019; and August 2, 2019, through July 31, 2021. Data as of March 31, 2023. Past results are not predictive of results in future periods.

In fact, not long after the 2011 credit rating action, U.S. stocks embarked on one of the longest bull markets in history — a virtually uninterrupted run from 2011 until the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“I think the lesson from 2011, and a subsequent debt ceiling impasse in 2013, is that these events can disrupt markets for a while — sometimes even weeks or months — but if we look at history, they don’t tend to have a lasting impact on investors,” Miller says. “That’s assuming we get a reasonable resolution.”

On Wednesday, House Speaker Kevin McCarthy unveiled legislation that would raise the debt limit by $1.5 trillion. The bill also includes several other provisions to curtail federal spending. It remained unclear whether there were enough votes to pass the bill in its current form.

What happens if the U.S. defaults on its debt?

Of course, the worry is that the U.S. could — in the middle of a particularly nasty debt ceiling impasse — wind up in technical default on its many debt obligations, including payments to bond holders. It’s hard to predict what might happen next, but there are many who say it would roil the financial markets and jeopardize the U.S. dollar’s status as the world’s reserve currency.

The chances of a technical default — which would occur should a bond payment be missed or even delayed — are very low but not zero, according to Tom Hollenberg, a Capital Group fixed income portfolio manager.

“It's important to make a distinction between the situation we are facing in the U.S. and something much worse, like an Argentina-style default, where investors lose their savings. Nobody seriously believes that will happen here,” Hollenberg says. “In the U.S., the probability of even a technical default, or a delayed payment, is between 5% and 10%, in my view. It’s certainly not my base case, but it’s something I can’t ignore either.”

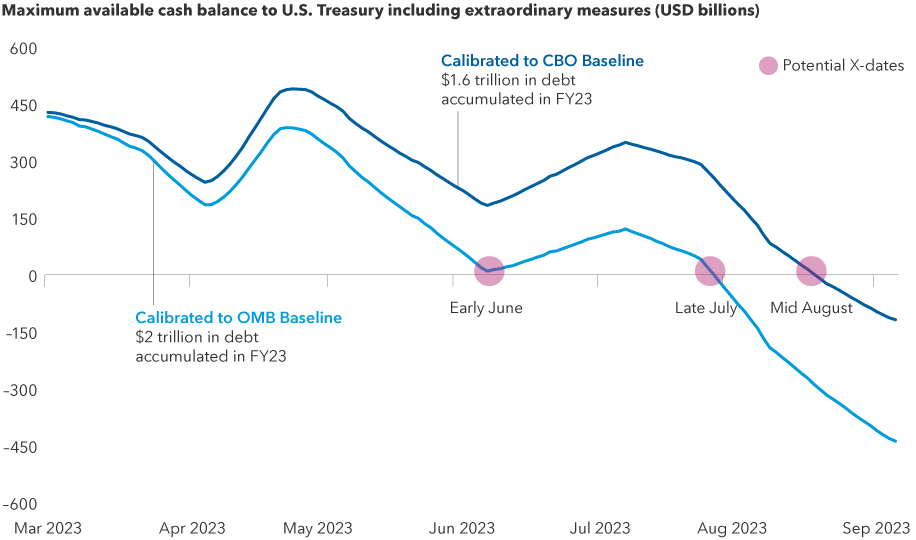

When will the U.S. Treasury run out of money?

Sources: Capital Group, Congressional Budget Office (CBO), Office of Management and Budget (OMB), Piper Sandler. Cash balance figures reflect estimates from Piper Sandler based on debt forecasts from the CBO and OMB, respectively. Estimates assume extraordinary measures are fully deployed and that the Treasury will not allow cash balances below $25 billion. "X-dates" refer to the date on which the U.S. government will be unable to pay all its obligations. Cash balance path is smoothed. As of April 12, 2023.

If the U.S. missed a payment on a short-term note due in June, for example, it would spark an outcry in the markets, accompanied by extreme volatility for a day or two, Hollenberg explains, and then the debt ceiling impasse would likely come to an end.

“When you reach a crisis, that tends to put the political gears in motion,” he adds. “If that happened, I think Congress would very quickly come together and raise the debt limit, and investors would be made whole.”

The law of unintended consequences

That doesn’t mean there would be no consequences for a technical default. The rating agencies could slash the U.S. credit rating again. Investors could drive up the cost of future U.S. debt issuances. And, perhaps worst of all, some investors may no longer regard U.S. Treasuries as the safest investment in the world.

“We don’t really know what the downstream implications would be,” Hollenberg says. “For example, there are banks whose ratings are somewhat linked to U.S. sovereign ratings. There are insurance companies in the same situation, as well as agencies like Fannie and Freddie. It’s difficult to know what would happen to them if one or more of the rating agencies were to downgrade the U.S. again.

“We could wind up with cascading downgrades, and that would be a real problem for some financial institutions,” he warns. “It’s not something we can just gloss over, and it’s why we need a timely resolution. I do think we will get one, I just hope it comes before we encounter any unintended consequences.”

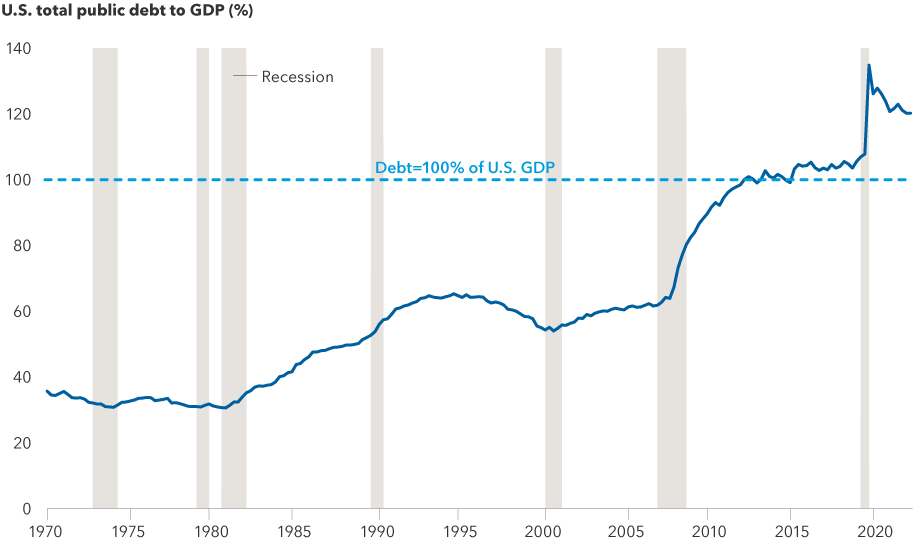

U.S. long-term debt has risen steadily over the past half century

Sources: Capital Group, National Bureau of Economic Research, U.S. Treasury Department. As of December 31, 2022.

How much debt is too much?

From the point of view of an equity investor, the U.S. debt ceiling debate makes for interesting political theater, but it’s not something that weighs too heavily on investment decisions, says Steve Watson, a portfolio manager with New Perspective Fund®.

“At the same time, I don’t think it’s necessarily a bad idea to have an occasional reminder that the United States is more than $30 trillion in debt,” Watson notes. “Maybe it’s time to engage in a serious discussion about long-term fiscal responsibility.”

The S&P 500 Index is a market capitalization-weighted index based on the results of approximately 500 widely held common stocks. The index is unmanaged and, therefore, has no expenses. Investors cannot invest directly in an index.

Matt Miller

Matt Miller

Tom Hollenberg

Tom Hollenberg

Steve Watson

Steve Watson