Planning & Productivity

Planning & Productivity

As a financial advisor, a big part of your job is focusing on goals and helping clients achieve them. But are you doing the same for your practice? In business, as in life, reaching a new goal requires setting it first. And the goals you set and how you plan to achieve them may make all the difference to your bottom line.

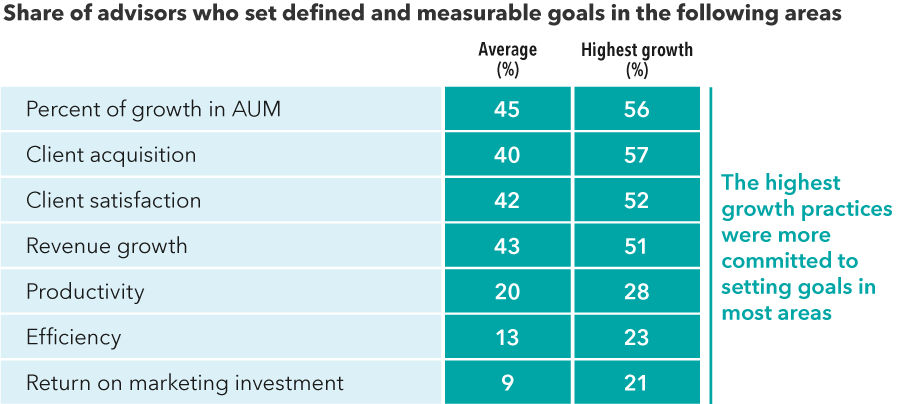

According to Capital Group’s Pathways to Growth: 2022 Advisor Benchmark Study, allocating more time to planning and goal setting can lead to enhanced growth. The highest growth advisors we surveyed were 42% more likely to do business planning, and were more intentional about goal setting in areas like efficiency, productivity, client satisfaction and growth in assets under management (AUM). The research findings also showed correlation between specific goals advisors track and measure to business growth. For example, while many of the advisors in our survey had goals for revenue, the highest growth segment also had goals for revenue growth, arguably a more sophisticated practice health measure.

“Advisors in today’s top teams are thinking like CEOs,” says Paul Cieslik, advisory practice management consultant at Capital Group. “These advisors are no longer running a practice — they are running a business.”

Successful business goal setting requires you to think big, but also to think intentionally based on the specific outcomes you want to see and the procedures you want to put in place. Here’s how you can start thinking like a CEO and get more strategic about goal setting and business planning.

High-growth goals

Setting and measuring goals is not just good for productivity; it is also correlated to business growth in our benchmark survey.

Source: Capital Group, Pathways to Growth: 2022 Advisor Benchmark Study

1. Keep goals structured and SMART

Whether you’re just getting started or refining your goal-setting process, it may help to have a few guardrails. Productivity specialists often recommend the so-called SMART guidelines, which call for business goals to be:

Specific: Rather than thinking broadly (i.e., “I want my business to grow”), specificity can help you find areas of potential incremental progress. For example, you may want the firm to increase clients with $1M+ AUM by 10% in the next year, or maybe you want to grow your multigenerational client base from 5% to 10% in two years. Then, get even more specific by asking what needs to be done to achieve the goal. Who will be responsible? Do you need a process behind it?

Measurable: Having quantifiable benchmarks — whether internal or industry-based — not only allows you to define what “good” looks like, but it also allows you to track your firm’s progress against it. As these benchmarks evolve with your firm, keep track of new and interesting ways to measure progress.

Attainable: How realistic is this goal? What are the chances of reaching it? In business, it helps to keep goals within the realm of the possible and aim for year-over-year improvement. You can also allow yourself progress check-ins to reevaluate attainability and even readjust goals based on unforeseen roadblocks.

Relevant: Successful goals are those directly tied to the needs of the business. You can and should find ways to tie each team member’s work to those goals. But goals for the sake of goals are a distraction.

Time-based: A timeline is part of a goal’s specificity. The team should know how much time will be allotted to achieve a goal, understand each person’s responsibility along the way, and know when progress check-ins will occur.

2. Track goals and get team buy-in

Perhaps as important as setting broad business goals is sharing them with your team. Goals should be communicated widely within the organization and can even be aligned to annual employee performance reviews. “Having stated objectives allows the best teams to measure their progress,” says Michael Schweitzer, head of High Net Worth at Capital Group. It’s all part of a transition, he says, to turn your practice into an enterprise.

Often, firms set annual goals and check in on quarterly progress to measure success or make any adjustments in strategy needed to make the goals attainable. But knowing what “good” looks like may require using key performance indicators (KPIs) — business metrics that allow you to quantify success. Certain KPIs are commonly used to gauge an advisory practice’s health, such as assets under management, total revenue, number of households served and client retention. Additional KPIs may be used to drive and measure the unique goals of your practice.

For example, if your firm is paid as a percentage of AUM, you may want to measure revenue from new clients separately from growth due to market performance. KPIs for profitability can include not just total revenue, but also operating profit (which is revenue minus expenses) or average revenue per client (which helps you get a better sense of profit margins and determine whether you need to target higher net worth clients). To gauge productivity, you might look at revenue per staff or operating profit per staff.

One particular KPI to be aware of is cost of service, Cieslik says. Calculated as expenses divided by total clients, cost of service helps you accurately price your services, he says.

Goals can even be used to support firm milestones or transitions like succession, says Cieslik. “Do you want to maximize the value of your firm when you retire? Or to generate some percentage of a revenue trail for a certain amount of time after you leave? If so, you need to think about goals for expenses and acquisitions,” he says.

Along with goals for revenue generated from existing clients and new clients, advisors set even more detailed goals for acquisition. For example, among the highest growth advisors in our benchmark, 21% set goals on marketing return on investment, compared to just 9% for all respondents.

A KPI for every goal

There are many ways to measure success in your practice. Here are some key performance indicators worth considering.

| Goal | KPIs |

| Business growth | AUM growth |

| Revenue growth | |

| Growth in total households served | |

| Revenue from new clients | |

| Revenue from market performance | |

| Profitability | Net profit margin |

| Operating profit | |

| Total expenses (direct and overhead) | |

| Client acquisition | Net new clients |

| New client revenue | |

| Referral rate | |

| Referral conversion rate | |

| Time spent onboarding | |

| Client satisfaction and retention | Client retention rate |

| Recurring revenue | |

| New revenue from existing clients | |

| Net promoter score | |

| Customer lifetime value | |

| Efficiency | Net profit per client |

| Time spent per client | |

| Average revenue per client | |

| Average AUM per client | |

| Average revenue per advisor/staff | |

| Average AUM per advisor/staff | |

| Operating profit per advisor/staff | |

| Team management | Employee satisfaction rate |

| Employee engagement rate | |

| Career plan progress | |

| Marketing and technology | Return on investment |

| Conversion rate | |

| Revenue attribution |

Source: Capital Group research

3. Turn outcomes into processes

When your firm is in the first years of strong growth, your initial goals may be based on outcomes or results you wish to achieve. For example, you may want to set an annual goal to increase your client base by a certain percentage, to gain a certain number of referrals or attain a level of assets under management.

As your business matures, your focus may shift to the actions, systems and processes that lead to desired outcomes to make them happen. Instead of just focusing on the result, focus on process goals that support you in reaching that result.

For example, say you have an acquisition goal to increase your client base. The processes that support this goal may include standard operating procedures to ask every top client for referrals as part of an annual meeting, to reach out to 10 new clients a week, or to hold one seminar a month. Your onboarding processes may further support this goal.

Having processes in place is a key part of turning your practice into an enterprise, says Schweitzer. They can also help empower your team to delegate responsibilities. “If you have a set of service standards, when a problem arises, everyone knows how it will be solved and how you'll communicate that to the client,” he says.

4. Avoid setting too many goals

Whether you are setting annual business goals or shorter term personal goals, success hinges on selectivity. But this is no easy task. Former President Dwight D. Eisenhower put it best when he said:

“Who can define for us with accuracy the difference between the long and short term! Especially whenever our affairs seem to be in crisis, we are almost compelled to give our first attention to the urgent present rather than to the important future.”

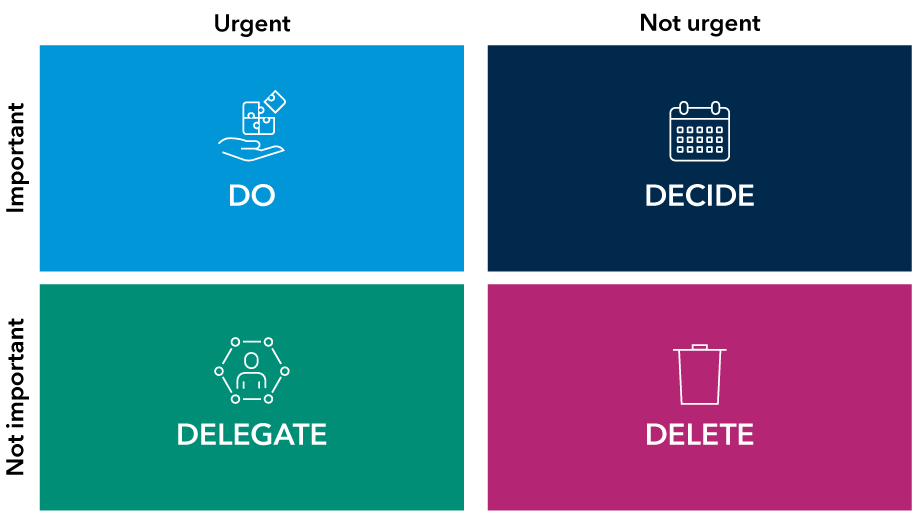

For this reason, productivity experts often recommend using the “Eisenhower matrix” to determine and prioritize business and personal goals.

The goals edit

The simple but effective Eisenhower matrix is recommended by productivity specialists like Stephen Covey, author of The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People, to organize both business and personal goals. The matrix consists of four quadrants on two axes: importance and urgency. The top left quadrant is the most important and urgent, and the bottom right is the least. You can further label these boxes: do, decide, delegate and delete. Use this tool to help sort out not just quarterly and annual goals, but also your own weekly and daily goals.

Source: Stephen Covey, The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People.

Even with the matrix results, goal setting may still feel overwhelming if there is too much to take on at once. This is why limiting goals can be a good strategy to help you stay on track. You may want to start with three goals or fewer per quarter, supported by no more than three specific weekly activities.

You can even use the Eisenhower box to prioritize daily goals, with a similar limit of three things you can commit to accomplishing each day. Cieslik suggests dividing your day into 15-minute increments and scheduling your to-do list to fit this framework. Tasks like client meetings may need three or four blocks to complete, but looking at your daily objectives in this way can help you stay on schedule. For example, in client meetings, you can segment a portion of time to catch up on personal issues. “You can still give the meetings a personal touch — just have time planned to talk about family updates,” Cieslik says.

SUPPORTING MATERIALS

Paul Cieslik

Paul Cieslik

Michael Schweitzer

Michael Schweitzer