Chart in Focus

Technology & Innovation

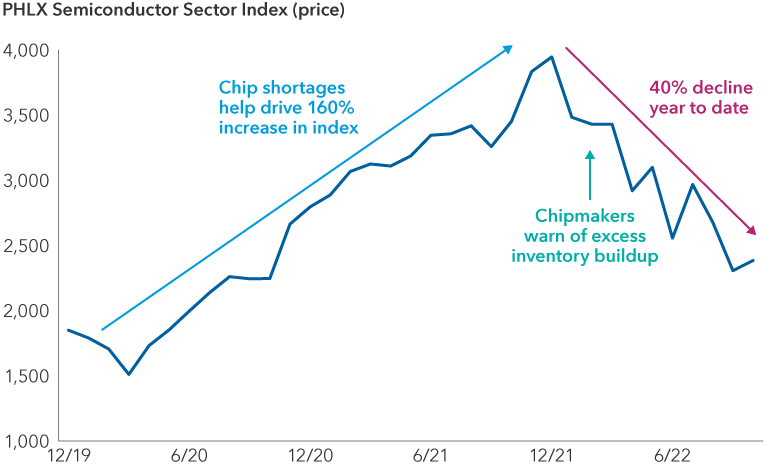

How fast things can change: There was a major shortage of semiconductors at the start of the pandemic, and now the industry is grappling with too much inventory in parts of the supply chain. This has led to a selloff in semiconductor stocks and prompted questions about the depth and duration of this downturn.

The U.S. has also stepped up restrictions on shipments of semiconductors and related equipment to China. Meanwhile, the U.S. and the European Union have laid out plans to reshore semiconductor manufacturing in the interest of national security, which is expected to have longer-term implications for industry efficiency and chip prices.

I recently visited Taiwan, Japan and South Korea, where I met with company management teams and some key industry contacts. Here are some of my current ideas about the state of the semiconductor business.

1. Is this current downturn different than previous semiconductor cycles?

Every cycle is different, and it is difficult to estimate the duration and severity of any slump. However, it would be a mistake to compare this period to previous downturns.

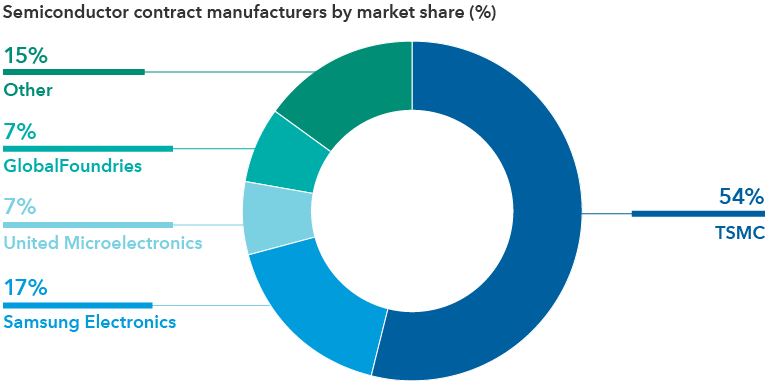

In the 2000–2010 period, most semiconductor downturns were related to supply imbalances that typically took some time to resolve. Multiple foundries were competing for business — sometimes against their own customers — and memory companies in Taiwan and Japan aspired to gain market share. The semiconductor equipment market was also a lot more fragmented. The industry today is more consolidated, and demand is more sustained as semiconductor content has proliferated into everyday applications. Three companies control most leading-edge global chip production: TSMC (Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing), Samsung Electronics and Intel. Furthermore, the market share of the top five equipment makers has risen to roughly 75% from 40% in the early 2000s.

The current downturn is meaningful, but I believe it is manageable. The slowdown began to manifest in the second quarter of this year when waning demand for consumer electronics, personal computers and smartphones led to a surge in chip inventories. I believe the industry has acted decisively: There have been cuts to previously announced capital spending plans and efforts to curb expenses. The memory chip industry is already an oligopoly led by Micron Technology, SK Hynix and Samsung. These companies have all announced plans to cut capital expenditures far earlier than we’ve witnessed in previous downturns.

Chip stocks have crumbled on inventory and geopolitical concerns

Sources: Capital Group, Refinitiv Datastream. The PHLX Semiconductor Sector is a Philadelphia Stock Exchange capitalization-weighted index composed of the 30 largest U.S. companies primarily involved in the design, distribution, manufacture and sale of semiconductors. Data as of October 31, 2022.

Overall, my sense is that inventories of logic semiconductors, which work as the brains of electronic devices, likely peaked in the third quarter, while inventories of memory chips, which help store data, are still rising and might peak in mid-2023. A correction in analog chips (used in circuits to control signals to logic chips) will likely be slower given their longer product obsolescence cycle and relatively stable pricing. The risk of accruing excess inventories of more advanced chips is lower, because the threat of product obsolescence limits hoarding behavior among distributors and manufacturers.

2. Can the world achieve some semblance of semiconductor self-sufficiency?

My view is no — and I do not think that governments are targeting self-sufficiency. I do believe, however, that the U.S. government will likely be more relaxed if critical advanced chips and the chips for military applications are fabricated on U.S. soil.

After two decades of consolidation, Taiwan dominates the global manufacturing of both leading-edge and less-advanced semiconductors. Together with China, Taiwan also controls most of the market for the testing and assembly of chips and many other parts of the value chain. This has obviously caused a lot of consternation among investors and governments in developed Western countries, especially given heightened geopolitical tensions between the U.S. and China and speculation around China’s desire to reunify Taiwan with the mainland.

The challenge is that when it comes to leading-edge semiconductors, many company road maps lead to Taiwan. TSMC works with more than 500 customers worldwide and is the global leader for producing chips at the most advanced-process nodes. The company is currently working with U.S. companies Apple, Nvidia, AMD, Intel and Qualcomm on their next-generation chips for smartphones, video game systems and virtual reality gear. Plus, TSMC is a key maker of data center chips for Google, Amazon and Microsoft.

Taiwan plays an outsized role in chip manufacturing

Sources: Capital Group. Data as of 2020. TSMC = Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corp.

TSMC reportedly plans to build a second fabrication plant in Arizona to manufacture more advanced 3-nanometer (nm) chips. Production is slated for the second half of 2025, nearly a year after starting 5nm manufacturing in its first fab in the same location. TSMC has indicated that more than 20% of its manufacturing will be outside Taiwan in the next few years, which might not seem to be that much. However, it would be nearly half of all its leading-edge chip production. I believe that these Arizona fabs will be enough to support all defense-related semiconductor manufacturing and other critical leading-edge chip requirements of the U.S.

Going beyond the strategically critical chips will be tough. The production of more mature chips is concentrated in Taiwan and China; while not impossible to move, it does not seem necessary and offers no strategic advantage. Taiwan and China also are leaders in assembly/test capacity.

3. What are some ramifications of reshoring semiconductor supply chains?

The CHIPS and Science Act of 2022, which provides $52.7 billion for American semiconductor development, and a new fund established in Europe aim to bring production to these developed markets. But there’s no doubt that doing so will raise prices. It’s estimated that manufacturing processors in the U.S. could cost 30% to 40% more than in Taiwan and about 15% to 20% more than in South Korea, where most of the current capacity lies.

I believe TSMC will likely shift to a pricing model in which it charges a blended average rate regardless of where it makes the chips. This approach has the potential to support higher prices for chips for some time, reversing the trend of steady price declines that we have seen in the past. In 2023, TSMC plans to increase prices by 6% for all its customers to help mitigate the costs of its overseas expansion in the U.S., Japan and China, which will also be inflationary.

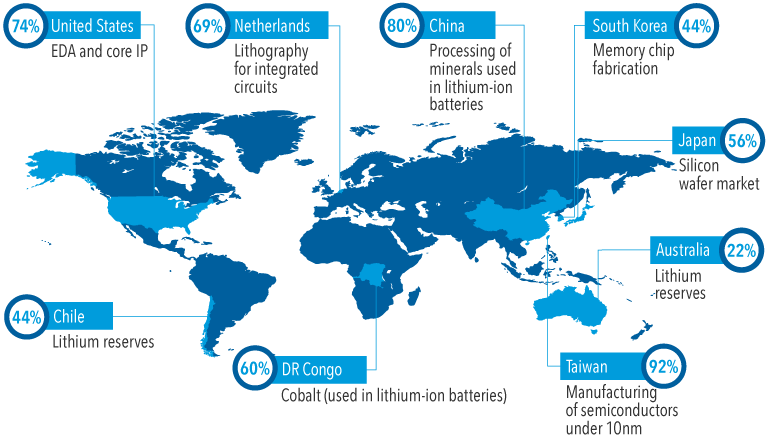

Secondly, rewiring the semiconductor supply chain will be a challenge. The high cost of manufacturing and specialized knowledge required are large hurdles that the industry and policymakers must overcome. One pressing need is for the U.S. to create a larger pool of qualified engineers to run fabs. This won’t happen overnight. By one estimate, Taiwan has roughly 300,000 such engineers, compared with 180,000 in the U.S.

Also, I don’t expect a complete decoupling of the global semiconductor supply chain. A large infusion of capital does not guarantee success or self-sufficiency for any country involved in semiconductors; China is a good example, having reportedly spent $100 billion to build out its domestic chip industry. Furthermore, the sophistication of producing and designing leading-edge semiconductors has grown exponentially — and requires not only the best and brightest talent in the world but also physical materials and tools from various countries.

The semiconductor industry uses a highly specialized global supply chain

Source: Capital Group, from White House analysis based on data from SEMI. Data as of 2019. EDA = electronic design automation. IP = intellectual property. NM = nanometer.

4. What are potential impacts of the latest U.S. restrictions on semiconductor exports to China?

The U.S. government is stipulating that U.S. chipmakers must obtain a license from the Commerce Department to ship advanced semiconductors and related equipment to China. The restrictions also target shipments from foreign firms that use U.S. equipment.

The measures are no slam dunk. The Biden administration will have to persuade other countries to help impose the restrictions. Based on my recent conversations, I believe that Japanese semiconductor equipment makers are largely on board, while Dutch and South Korean manufacturers seem to oppose controls on equipment sales to China. The Commerce Department is trying to restrict even legacy equipment sales to the Chinese customers currently on its Unverified List (ineligible to receive items subject to the Export Administration Regulations). The aim is to pressure these companies into agreeing to audits and inspections. Success with these restrictions will require all other countries to cooperate, and there is a real risk that U.S. companies could be excluded from future design needs of domestic Chinese firms.

In the long run, memory-chip makers appear to be likely beneficiaries of U.S. attempts to curb the development of China’s semiconductor industry. Recent measures could undercut the growth of China’s state-run memory-chip companies while helping American companies that manufacture processors on U.S. soil.

5. Which industry drivers could power the next upturn?

Despite the sharp selloff in semiconductor stocks, I believe that semiconductors remain a secular growth industry and governments have taken notice. They are essential to security, energy and the overall productivity of economies around the world.

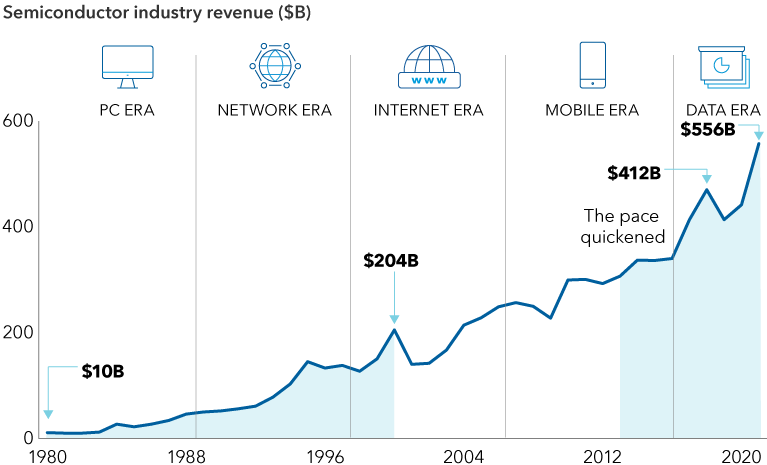

Consider this: It took 40 years for the semiconductor industry to reach its first $200 billion in sales — and only another 17 years to achieve the next $200 billion. I believe that these leaps in sales will happen at an even faster rate over the next decade.

The pace of semiconductor sales is accelerating

Source: Capital Group, Statista, WSTS. Data as of December 2021.

Demand for high-performance computing chips (HPC) used in cloud computing and artificial intelligence (AI) functions is a potential driver of further industry growth, with an increase in silicon wafer size rather than unit growth a significant trend within machine learning and AI. Electric vehicles have twice the silicon content of conventional cars, and 5G phones use about 40% more processors than 4G phones. What’s more, demand is growing for virtual reality and augmented reality products. So despite this latest downturn, I believe the industry is positioned to benefit from these powerful tailwinds in the years ahead.

Shailesh Jaitly

Shailesh Jaitly