Client Relationship & Service

Demographics & Culture

- Your clients expect you to talk to their children about financial matters.

- Even children below the age of 12 are ready to learn about money.

- There are strategies to keep money lessons for children on topic.

Want to provide a valuable service to your clients? Talk to their children about money. They may even be expecting you to.

Telling children to clean up their rooms and do their homework is something parents usually handle on their own. But when it comes to imparting financial wisdom, they look to advisors, according to a Capital Group-sponsored survey conducted by APCO Insight in April 2018. Financial advisors ranked third, right behind parents themselves and schools, when parents were asked who they expect to teach their children about financial matters.

Who should prepare our children?

Percentages indicate participants who ranked a response in their top three.

Source: Capital Group-sponsored survey conducted by APCO Insight, a global opinion research firm, in April 2018. The research consisted of an online quantitative survey of 1,202 American adults — 402 millennials (ages 21 to 37), 400 Gen Xers (ages 38 to 52) and 400 baby boomers (ages 53 to 71) — of varying income levels who have investment assets and some responsibility for making investment decisions for their families. The overall sample reflects national representation on key demographic measures according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

Filling a financial education gap

Advisors can help fill an important role not met in other places. Most schools don’t have programs to teach children about creating a budget, much less about how to invest. Meanwhile, parents don’t feel confident they’re up to the job either, with only 19% describing their efforts as completely successful.

Parents aren’t ducking their duty due to lack of interest: Nearly half of mothers and a third of fathers surveyed wished they’d learned about money matters sooner themselves. It’s a way to reach young millennial parents too, as 39% of them said they would start telling children by age 12 to start saving early.

How to be an advisor-teacher

Clients might want you to talk to their children about money, but what if you don’t see yourself as a teacher? How do you begin the conversation, and what do you talk about?

Parents shared five pieces of financial wisdom they hope their children will pick up. Here are five questions to help you start the conversation:

1. ”Do you spend less than you earn?“

You might be tempted to jump right into the process of how to build a portfolio and similar, more advanced topics. But when talking with children, start with the basics.

More than half of the parents (56%) polled said teaching children to live within their means was one of their top three recommendations for a child, teen or young adult. Don’t think financial discipline is something you’d only discuss with people in their 20s. “Managing and avoiding debt” is something that 46% of respondents have already started or plan to talk about with children as early as in their teens.

How to approach it: Ask children about their weekly or monthly allowance. If they don’t receive one, perhaps suggest parents begin to pay one. That will help build trust with children right away. Managing an allowance is a way for children to understand how to balance their wants with their cash flow. Warren Buffett received a nickel-a-week allowance and used that as a basis to determine how much candy he could buy — or money he could save.

Help children understand how an allowance sets a baseline for spending. It’s also the foundation of a budget.

2. ”Do you have a budget?“

Creating and sticking with a budget can be the financial equivalent of eating your vegetables. Many people need to be reminded of how important budgets are. The importance of budgeting is clear, though, as one in five adults polled chose budgeting as one of their top lessons.

How to approach it: Make budgeting real and personal — not theoretical. Create an actual budget or help the child create one for themselves. For older children, sit down with a sheet listing their expenses and discuss where their money is going. Help them discover any imbalances and correct them. For younger children, however, it’s useful to take out three labeled jars. The first one, “Spending,” is where the child can put money that they are free to use for anything. The second jar, “Saving,” should be dedicated to short-term financial goals, such as a toy or other treat that exceeds their allowance. Use the third jar, “Investing,” to teach children how to put away money that will be allowed to grow over time. Proceeds from this jar can be used to start building a portfolio.

3. ”When is the best time to start saving and investing?“

Saving early puts the power of time on your side, a lesson that parents want their children to learn. More than 40% of respondents said prioritizing early saving behavior is key to a good financial start in life. However, this concept can be more difficult for some children to grasp.

Sure, the “time value of money” and “compounding” are the forces that make getting started early so powerful. But most children won’t respond to economic terms and might even shut down if they think you’re taking them to school.

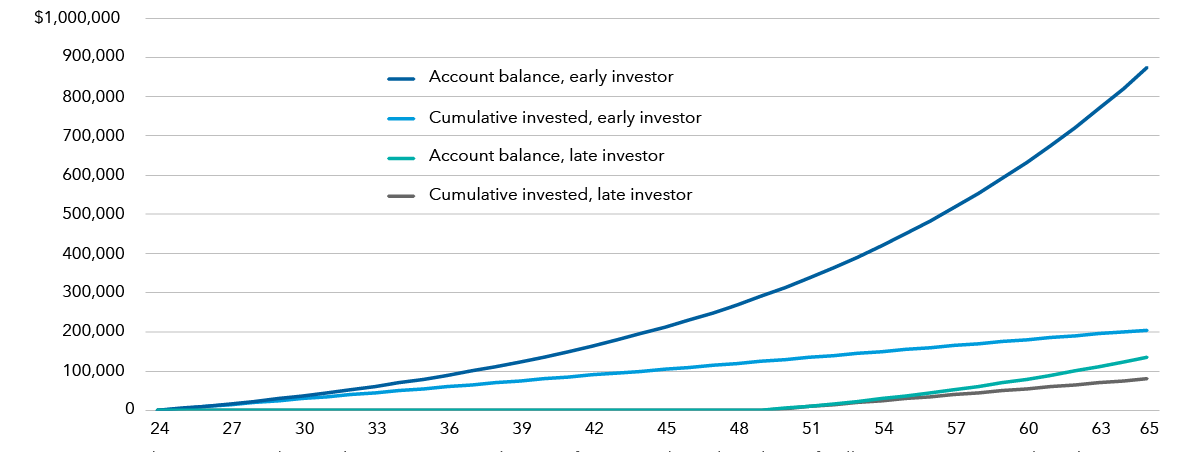

How to approach it: Talk in terms of dollars and time. A variety of charts can be used to show children why giving up a small amount of spending now can open opportunities in the future. Consider using a chart that shows how a person who starts saving $5,000 a year at age 25 could wind up with $874,000, while someone who doesn’t start saving $5,000 a year until turning 50 would have just $136,000. Show them a picture of what they could buy with the $738,000 difference. Hint: A brand new Ferrari California costs about $200,000, so they could buy several.

Start early: End up with more

The early investor who saves $5,000 a year starting at age 25 can end up with nearly $900,000 when they’re 65, while the late investor who saves $5,000 a year starting at 50 has just $136,000.

Source: Capital Group research. Based on average annual return of 6%. Hypothetical results are for illustrative purposes only and in no way represent the actual results of a specific investment.

4. ”What’s a 401(k) match?“

Mentions of ERISA and 401(k)s are all but guaranteed to turn off most children. But that doesn’t mean parents don’t see these concepts as important. Roughly a third of respondents included “take advantage of your employer’s 401(k) match” among their top pieces of financial wisdom. The key is to explain, in a way that resonates, the wisdom of using these accounts.

How to approach it: Avoid the temptation to get into the mechanics. Instead, make it real. Tell the child if they put $5 of their weekly allowance into their savings account, their parents will put in an additional $1. Ask the parents to set up the account and ask their child weekly if they want to save the money or receive the cash, and then make the matching contribution if warranted. Explain how the matching money is a benefit that some jobs offer. Seeing real money being contributed to the account as a result of their saving will underscore its value and make it tangible.

5. ”What are credit cards for?“

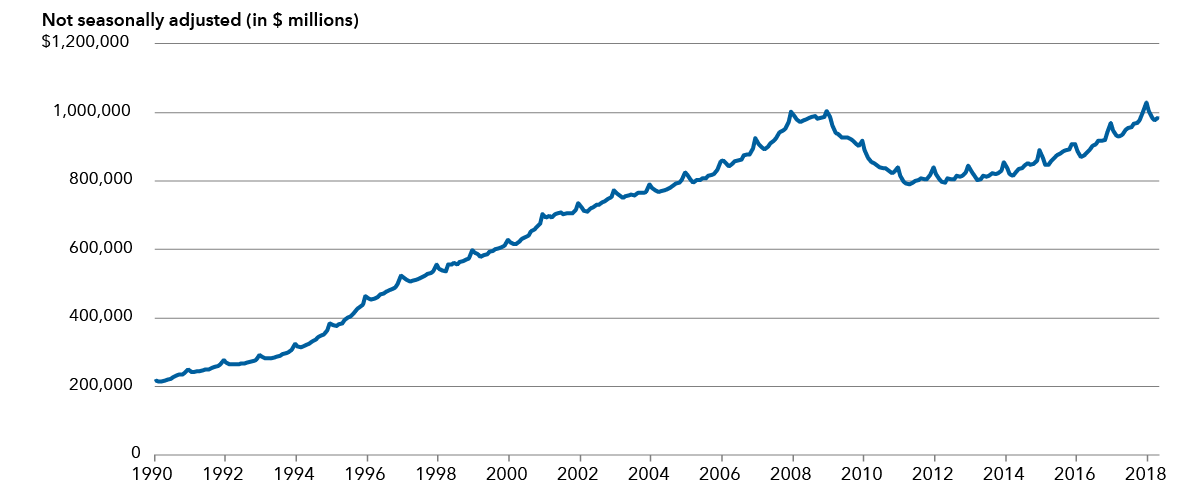

Credit cards can be a valuable financial tool but can lead people into financial distress if used improperly. The ease of credit, relatively high interest rates on credit card debt and lack of supervision can result in crippling debt. Nearly 30% of parents want children to know how to manage credit effectively and avoid carrying a balance. Nonetheless, credit card balances continue to swell, according to data from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. The Federal Reserve’s tally of revolving consumer credit, which is mostly credit card debt, is once again nearing the records set in 2008.

Consumer debt — including credit card debt — is rising

Consumer credit outstanding (revolving)

Source: Federal Reserve

How to approach it: Children understand interest rates, just not those exact terms. Borrowing and “paying back” is a routine activity on schoolyards and a good way to explain this concept.

Ask the child, “Have you ever borrowed money to buy lunch?” Ask how much they borrowed. Most likely, they borrowed $3 and paid that exact amount back. Explain that they might have used a credit card instead, as that’s also a loan, but in this case the longer they wait to pay it back, the more they’d have to return. That $3 lunch could easily end up costing $4 if they waited a year to pay it back.

Read more about what parents told us they are thinking about when it comes to preparing their children to save and invest. Download our full research report on the topic.

RELATED INSIGHTS

-

-

Traits of Top Advisors

-

Practice Management

Use of this website is intended for U.S. residents only.