Chart in Focus

Economic Indicators

The global economy has managed to avoid a recession in recent months, thanks to resilient consumers, a surge in travel and leisure activities, and the reopening of China’s economy following pandemic-related lockdowns.

That’s likely to change in the second half of the year, says Capital Group economist Jared Franz, as the impact of high interest rates, inflation and a banking sector crisis combine to tip the world into a mild recession.

“Global economic growth is on track to decline by roughly 1% for the full year, in my view,” Franz explains. “That should be followed by fairly robust growth in 2024, driven by strong consumer spending and potentially lower interest rates in the U.S. and Europe.”

An inverted yield curve has often preceded recessions

Sources: Capital Group, Bloomberg Index Services Ltd., National Bureau of Economic Research, Refinitiv Datastream.

As of May 25, 2023.

Many economic indicators are pointing to a recession in the United States, not the least of which is an inverted yield curve. That happens when yields on short-term U.S. Treasury bonds are higher than yields on long-term bonds, indicating that investors expect tough economic times ahead.

“The yield curve is more inverted now than it has been since the 1980s,” Franz notes. “Of all the recession indicators, it has been the most accurate one.”

Looking at the major economies around the world, the U.S. may decline by 1%, Europe should remain flat to slightly negative, and China could grow 2% to 3%, according to estimates from Capital Strategy Research (CSR), Capital Group’s macroeconomic research team. CSR estimates are slightly below consensus estimates, largely due to the view that inflation could remain at higher-than-expected levels.

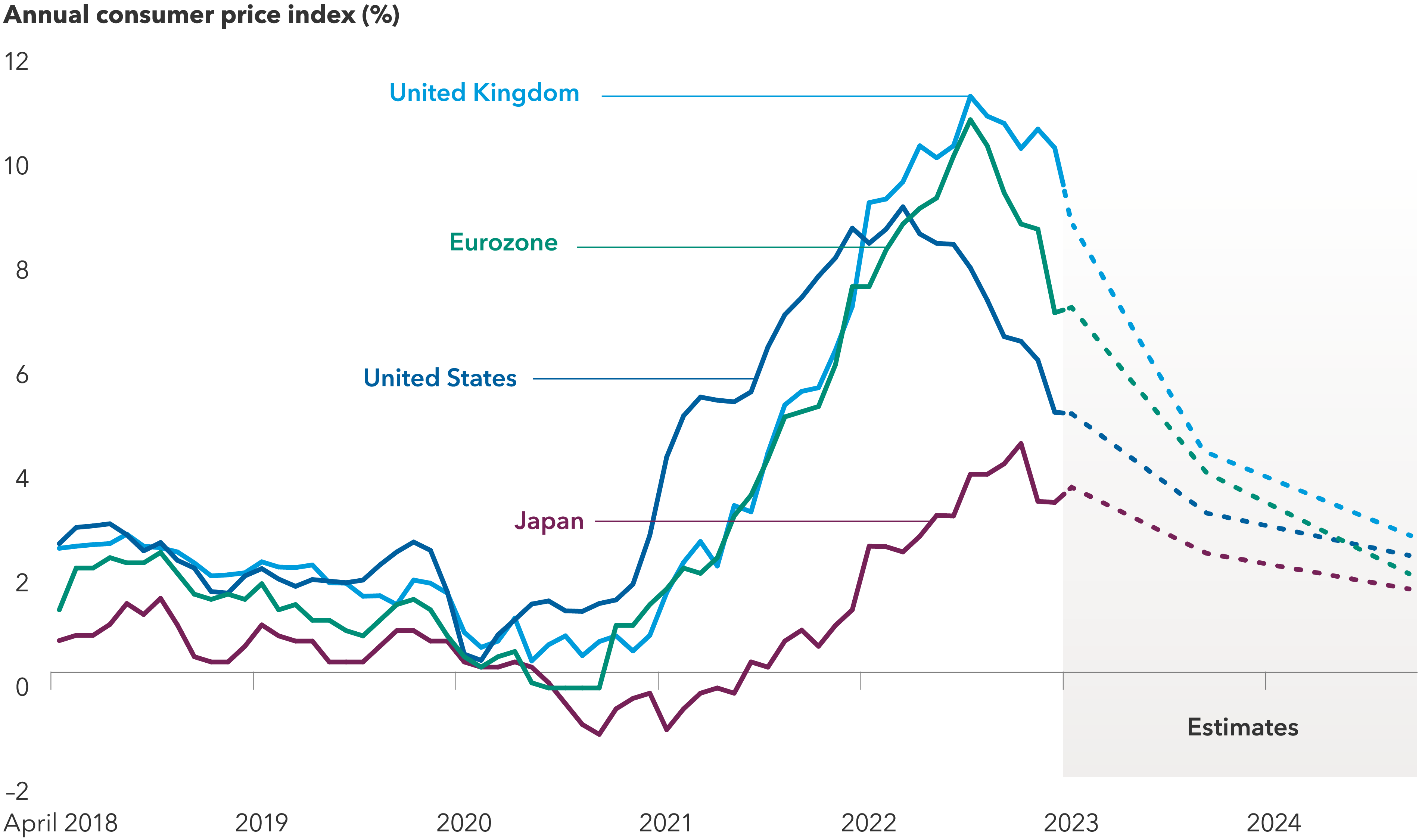

Inflation is less onerous today, but remains elevated

Sources: Capital Group, FactSet, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Eurostat, UK Office for National Statistics, Japanese Statistics Bureau & Statistics Center, International Monetary Fund. Data as of May 25, 2023.

It may not feel like it at the grocery store, but inflation is on a downward trajectory in the U.S., Europe and across many other markets. That’s largely due to lower energy prices, fewer supply chain disruptions and aggressive interest rate hikes by central banks. Interest rate-sensitive industries, such as housing, are already feeling the effects, with home prices falling in some formerly hot markets.

Rate hikes meant to fight inflation have also triggered a crisis in the banking sector. A sharp selloff in the bond market last year hammered the portfolios of numerous regional banks, contributing to the collapses of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank. In Europe, contagion spread to Credit Suisse, which nearly collapsed before UBS agreed to buy it for more than $3 billion.

The next shoe to drop could be commercial real estate. Office vacancy rates are on the rise as more companies embrace work-from-home business models. At the same time, it’s become more difficult to refinance commercial real estate (CRE) loans that were taken out when interest rates were much lower. That could be a growing threat to banks with a large exposure to CRE loans.

“Office and retail properties look like the biggest concern,” says Ben Zhou, a Capital Group analyst who covers real estate investment trusts.

Interest rate outlook

Given these mounting risks, the interest rate outlook has changed dramatically since early March, when the banking crisis first hit. As shown in the chart below, investors no longer think the U.S. Federal Reserve will raise rates as far or as fast as previously expected, largely due to a tighter lending environment stemming from the banking turmoil.

“We knew there would be consequences to one of the most aggressive tightening campaigns in history,” says Pramod Atluri, principal investment officer of The Bond Fund of America®. “The dislocations we are seeing in the financial markets signal a painful new phase for the Fed. It has clearly exposed some vulnerabilities and, as a result, I believe we are nearing the end of this rate-hiking cycle.”

Investors expect interest rates to decline in the months ahead

Sources: Capital Group, Bloomberg Index Services Ltd., Refinitiv Datastream, U.S. Federal Reserve. Fed funds target rate reflects the upper bound of the Federal Open Markets Committee’s (FOMC) target range for overnight lending among U.S. banks. The market-implied rate is based on price activity in the fed funds futures market, where investors can speculate on where they think rates will be at a future point in time. As of May 26, 2023.

The European Central Bank has also slowed its rate-hiking campaign — from 50 basis-point increases previously to 25 basis points at its May 4 policy meeting. So far, ECB officials have not indicated a willingness to pause, given that inflation is running significantly higher in Europe than it is in the United States.

Even in the U.S., consumer price increases are well above the Fed’s 2% target. And there are growing signs that inflation in the range of 4% to 5% could be stickier than central bankers had thought it would be. On May 26, the U.S. government reported that core inflation rose 4.7% on a year-over-year basis in April, up from 4.6% the month before.

A key question going forward is: Will the Fed and other central banks be willing to let inflation run hot for a while? Or will they decide it’s more important to bring prices under control by keeping rates higher than market expectations?

“Central bankers find themselves in a tough spot and I don’t envy them at all,” Franz says. “In my view, the Fed is going to pause its rate-hiking campaign in order to assess the damage from the banking crisis, and they may even begin cutting rates by the end of the year.”

Jared Franz

Jared Franz

Ben Zhou

Ben Zhou

Pramod Atluri

Pramod Atluri