Tax & Estate Planning

Retirement Planning

You’ve probably heard this suggestion — converting your traditional individual retirement account (IRA) to a Roth IRA can help your money go further. It’s one of the most common conversations we have with clients.

Nevertheless, many clients hesitate to take the step. Sometimes that’s due to what can be a steep up-front tax cost; other times, people may be following a rule of thumb that doesn’t really apply to high net worth investors.

Needless to say, every situation is unique and in some cases conversions aren’t called for. But in my experience, it’s usually wise to convert from a traditional account to a Roth, and I urge you to talk to your Private Wealth Advisor and outside tax professionals about it.

There are three broad topics to consider when mulling a conversion: the direct benefits, the tax cost and the question of who will ultimately use the assets. Here’s a look at each:

There are compelling advantages to a Roth.

Traditional IRAs and Roths are both are tax-advantaged but in markedly different ways. A major distinction is when taxes are paid.

In a traditional IRA, initial contributions are typically tax-deductible in the year they are made, which can reduce taxable income in that year. Subsequent gains on those investments are tax-deferred, meaning the IRA holder doesn’t pay taxes until the money is withdrawn.

However, the eventual withdrawals are taxed as ordinary income. The growth compounds on a tax-deferred basis, but that means the associated tax liability also grows proportionally. And unlike capital gains, the taxes apply to every dollar withdrawn, whether they’re from gains or the deposits. So while you might not pay taxes on traditional accounts today, you’re delaying a tax bill that you or your beneficiaries will incur eventually.

Roths, by contrast, are tax-free once certain requirements have been met. Initial contributions are funded with after-tax dollars. However, the earnings on the underlying investments — and, thus, the eventual withdrawals — are tax-free. That’s a powerful feature that can add up over the long term.

In traditional accounts, federal income tax alone can eat up 37% of assets — and even more if state and local income taxes apply. Some clients can forfeit nearly half of the assets in such accounts to taxes.

There’s another appeal to Roths. With traditional retirement accounts, IRA holders must begin taking annual distributions — known as required minimum distributions, or RMDs — starting at age 73. That forces investors to annually liquidate a portion of their accounts, which erodes their balances and triggers tax bills. Roths don’t have distribution requirements during the account owner’s lifetime, thus lengthening the potential number of years for returns to compound. This benefit alone gives you a lot of control over how your retirement account will interact with your estate and how it can benefit your heirs.

And for clients who view these accounts as assets to pass on to their heirs, Roths offer additional planning benefits. With traditional accounts, the heirs inherit the assets and the tax liability. However, the conversion forces an owner to pay the tax liability up front. Thus, heirs receive a tax-free asset while owners may be able to decrease their estate size by the amount of the taxes paid with no gift tax implications.

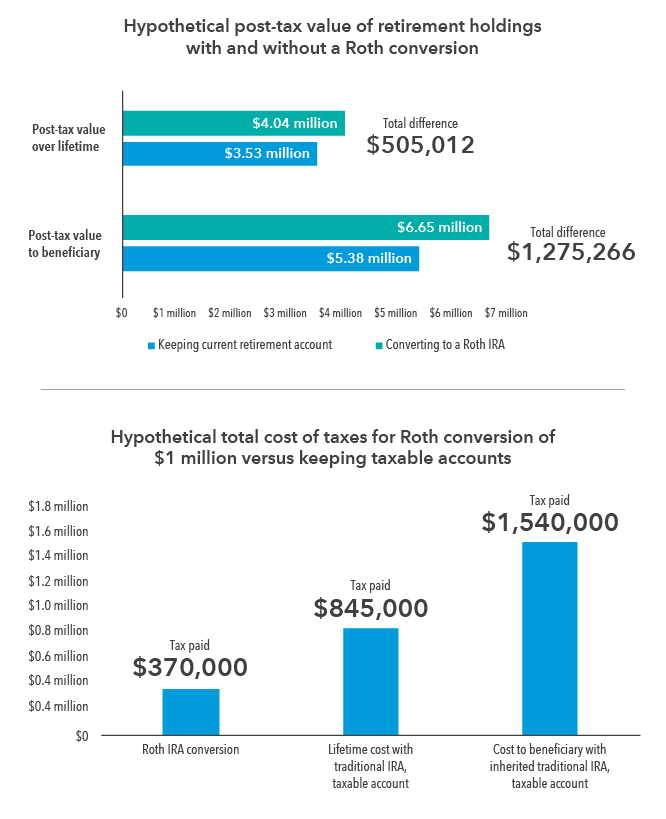

Converting to a Roth IRA could potentially save hundreds of thousands

Source: Capital Group. See important disclosures and notes on methodology at the end of this article. As of September 30, 2024.

There are many ways to handle the costs of conversion.

Not surprisingly, a primary deterrent to conversions is the upfront tax burden, which is added to that year’s taxable ordinary income. This can be made a little more palatable by the fact that you don’t have to switch to a Roth all at once. Conversions can be spread across multiple years, dividing the tax bite into smaller chunks that are easier to manage and plan for. This approach is certainly applicable to cases where converting the entire traditional account would push an investor into a higher tax bracket.

A critical element is how taxes are paid. It’s usually inadvisable to take assets from the retirement account itself. That would reduce the amount available to transfer, and the point is to put as much as possible into the Roth. To make the most of this process, consider earmarking available cash from another source to cover the tax liability.

The question of how much to convert — and when — should be weighed in conjunction with the possibility that a federal income tax overhaul is on the horizon. Current rates, which were reduced in 2017 under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), are set to expire at the start of 2026. That’s likely to make tax policy a big focal point in Washington regardless of the outcome of the November election, and there could very well be legislative action ahead of the deadline.

Nevertheless, the two parties have sharply differing tax plans and there is significant uncertainty about what comes next. If Congress and the next president take no action by the end of next year, the top income tax rate would revert to the pre-TCJA level of 39.6%. Thus, a timely conversion could prevent a higher tax bill.

Consider the ultimate beneficiaries before undertaking a conversion.

All of this said, as you make the decision whether to convert, you should consider the intended recipient of the assets. For example, if you plan to leave your retirement account to your favorite charity, it makes no sense to pay conversion taxes to ultimately donate them to a tax-exempt entity. In this case, keeping the assets in traditional accounts has merit.

Likewise, a conversion might not be right if you or your beneficiary would be subject to dramatically lower income tax rates when the time comes to make withdrawals. Our research shows, however, that rates would need to be much lower — perhaps lower than you might anticipate — to not consider a Roth based on this premise. Your Private Wealth Advisor can help you evaluate potential scenarios.

While there are several factors to consider, it boils down to this: While you might not pay taxes on traditional accounts today, you or your beneficiaries will pay them eventually — and, critically, those taxes will apply to your asset growth. A Roth conversion will effectively limit income taxes to your existing principal, giving you the full benefit of any future gains.

Add in the other benefits such as the elimination of lifetime required distributions, and a Roth conversion can be well worth it.

Illustrating the power of a Roth conversion

Let’s say a 60-year-old investor in the highest tax bracket has $1 million in a traditional individual retirement account (IRA). Their state and local governments don’t levy income tax, so they’ll owe 37% on any withdrawals. Our investor also has enough cash in a non-retirement account to convert their retirement account to a Roth IRA — in this case, that’s $370,000, or 37% of the $1 million in the account. Finally, we’ll assume that they’re investing in a mix of equities and fixed income that, in non-retirement accounts, would result in an effective tax rate of about 23.5% — a mix of income tax on dividends and bond payments, as well as capital gains taxes on stocks.

We’ll examine two scenarios. In the first, the investor will keep their traditional IRA and invest that $370,000 in a non-retirement account. In the second, the investor will spend the $370,000 to convert their retirement to a Roth.

At first, neither scenario has an advantage.

Initially, the traditional scenario has more funds on hand — $1.37 million — but any withdrawals on the $1 million or its returns in the traditional account will be subject to income tax. At that 37% rate, its after-tax value is $630,000; when combined with the $370,000 in the non-retirement account, that puts the total after-tax value of the holdings at $1 million.

The Roth scenario is less messy — after converting, the investor has $1 million in their account, but they won’t owe any additional taxes on qualified withdrawals.

Over the investor’s life, the difference becomes clear.

Using average life expectancies, we looked forward over the next 28 years to get a sense of what both scenarios might look like over the investor’s life. We assumed a total return of 5.1% for the portfolios, reflecting a mix of municipal bonds, investment-grade bonds and globally diversified equities.

In the traditional scenario, the accounts increased to an after-tax value of over $3.5 million. That accounts for the growth of the $1 million retirement account alongside the $370,000 investment, as well as a 37% income tax applied to all retirement withdrawals and income from the taxable account. Additionally, a 23.8% long-term capital gains/net investment income tax is applied to capital growth in the taxable account. Once required minimum distributions (RMDs) from the retirement account kicked in at age 75 (the age at which RMD are expected to begin for this investor), we assumed they were reinvested in the taxable account.

The Roth, however, fared far better, with its after-tax value topping out at just over $4 million. While this scenario started with fewer actual dollars in the bank, the funds were able to grow without any tax claims or RMDs, allowing it to pull ahead.

The gains can continue for your heirs as well.

We also looked out 10 more years in this simulation, examining how the investor’s heirs could benefit from a Roth rather than a traditional retirement account. We chose 10 years because, in most cases, an inherited retirement account must be liquidated within that time frame.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the Roth pulled ahead there, too. The traditional account’s final, after-tax value was nearly $5.4 million, more than $1 million lower than the Roth’s final after-tax value of just under $6.7 million. Again, the tax efficiency of a Roth was key to this outcome, giving the investor and their heirs the full benefit of powerful compound growth.

See below for important disclosures and notes on methodologies.

Capital Group Private Client Services does not provide legal or tax advice. For estate planning or taxation matters, investors should consult with a legal and/or tax advisor regarding their individual circumstances.

Roth methodology: The “Keeping current retirement account” (“keeping”) and “Converting to a Roth IRA” (“converting”) scenarios assume investors and beneficiaries pay 37% federal tax on ordinary income as well as a 20% federal tax and a 3.8% Medicare surtax on qualified dividends and long-term capital gains. They assume no state or local taxes. The keeping scenario assumes $1 million invested in an IRA account with an asset blend of 60% world equity/40% U.S. investment-grade bonds, and $370,000 invested in a taxable account with an asset blend of 60% world equity/40% municipal bonds. The converting scenario assumes $1 million in a Roth IRA account with an asset blend of 60% world equity/40% U.S. investment-grade bonds. In both scenarios, world equity is assumed to have average annual returns of 6.5%, average annual yields of 2.2% and average annual turnover of 40%. U.S. investment-grade bonds are assumed to have average annual returns of 4.1%, average annual yields of 4.1% and average annual turnover of 20%. Municipal bonds are assumed to have annual average return of 2.1%, average annual yields of 2.1% and average annual turnover of 20%. “Post-tax value over lifetime” (“lifetime”) scenario assumes 28 years of growth, based on the IRS Single Life Expectancy Table for a 60-year-old man. “Post-tax value to beneficiary” (“beneficiary”) scenario assumes an additional 10 years of growth after the lifetime scenario. Lifetime scenario assumes required minimum distributions (RMDs) are taken in the keeping scenario, beginning at age 75 based on the IRS Uniform Lifetime Table, and reinvested in a taxable account. Beneficiary scenario assumes RMDs are taken in the keeping scenario in years 1–9 based on the Single Life table, with the remaining balance withdrawn in the 10th year, and reinvested in a taxable account. Some values might not reconcile due to rounding. This material does not constitute tax or legal advice. As tax rates have an important role in the analysis, investors should consult their own tax and legal advisors.

Related Insights

Related Insights

-

-

Philanthropy

-

Wealth Planning

Aaron Petersen

Aaron Petersen