Portfolio Construction

The recent volatility in the financial markets demonstrates how prices can change direction quickly and with little warning. Equities have been pressured by fears of budding inflation and potentially higher interest rates.

Given the length of this bull market, the thought of a correction can be unsettling. Keep in mind, however, that periodic setbacks are both natural and necessary for long-running market advances. For investors, it’s important to keep these fluctuations in perspective. The best way to do that is to ensure you have the proper long-term asset allocation strategy based on your time horizon, risk tolerance, risk capacity and personal financial goals. That way you can stick with your portfolio’s objectives even during intermittent turbulence.

In addition, it’s important to build portfolios using our wealth pyramid framing structure. We begin with a “base,” which is made up of liquid funds that can support two years of spending. Next is “core capital,” or the amount of money needed to endow an investor’s lifestyle. Finally, any additional amount is considered “surplus,” which can be earmarked for other goals, such as philanthropic giving or wealth transfer to future generations.

At Capital Group Private Client Services, once we have determined a client’s goals, we can then design an appropriate strategic allocation tailored to each client’s personal and financial circumstances — for example, having sufficient exposure to high-quality bonds with a low correlation to stocks. Arriving at an appropriate portfolio allocation requires an understanding of the right balance between a client’s emotional tolerance for risk and the degree of risk they must take to accomplish their financial objectives.

While the allocation among stocks, bonds and other assets broadly defines the structure of individual portfolios, it’s important to remember that our portfolio managers have the flexibility to make adjustments within the investment strategies themselves. For example, they have leeway to increase cash positions or tilt investment holdings depending on circumstances in the broad economy and specific industries, subject to client restrictions.

Avoid the urge to time the market.

Regardless of market conditions, the natural human instinct among investors is to make portfolio adjustments based on what they think will happen. This impulse isn’t confined to periods when stock prices are falling — it’s equally tempting when they are rising. Just as some investors are inclined to reduce equity exposure following a market decline, others are reluctant to increase stock investments during a rising market because they worry that a correction might occur. While the instinct to time the market is understandable in either case, it’s potentially very costly. Selling near a market bottom “locks in” losses, and sitting on the sidelines during a subsequent recovery can cause an investor to miss out on meaningful gains.

In fact, history shows not only that it’s impossible to predict short-term market moves, but that retreating from stocks at the wrong time can significantly damage long-term returns. For example, a hypothetical $1 invested in the S&P 500 index in 1926 would have grown to $6,035 by the end of 2016, despite the sometimes sharp bear markets along the way. Missing just the best 40 months would have lowered the ending value to $34.75.

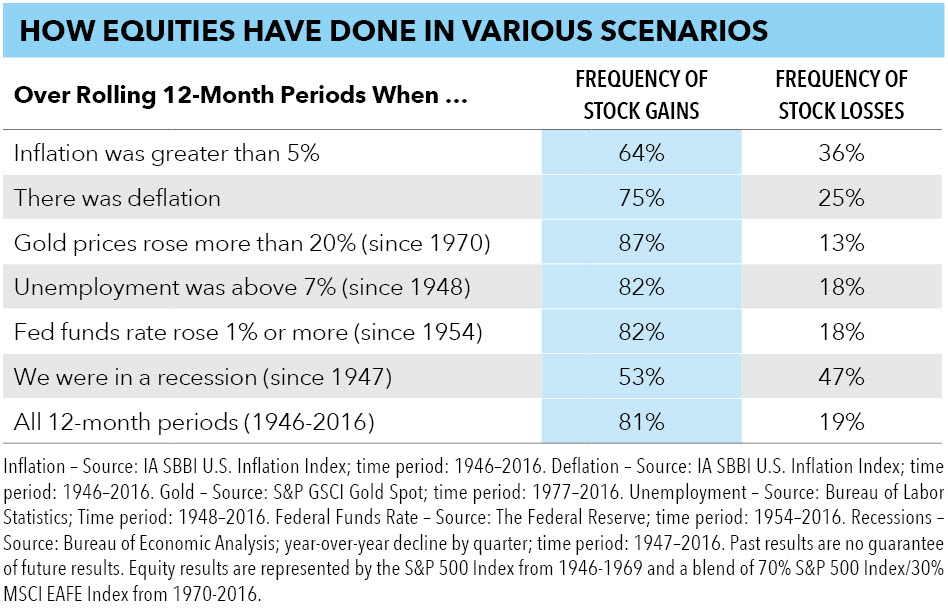

Our analytics team studied a range of postwar environments to gauge whether economic signals were a reliable precursor to market declines. In other words, they assessed whether it was possible to time the market based on economic red flags. Looking back to 1946, we found that stocks appreciated in 81% of all rolling 12-month periods, including both weak and strong environments.

We then looked exclusively at challenging times, such as when inflation was high, gold prices were surging or unemployment was elevated. Surprisingly, we found that equity markets delivered overwhelmingly positive returns even during these tumultuous periods. Only recessions seemed to have a reliably dampening effect on stocks, but avoiding those periods would have required advance warning. Unfortunately, even the most highly regarded economists are notorious for their conflicting — and often incorrect — views about when recessions will materialize.

Half of market declines are relatively short-lived.

Separately, we analyzed the length and severity of down markets to gauge the effects on client portfolios. Our research shows there are two basic types of market declines: major pullbacks, which often correspond with a recession, and shorter-lived downturns that occur in the course of longer-lasting market rallies.

In the postwar period, the S&P 500 dropped 15% or more on 16 occasions. Half of those were relatively mild, lasting less than eight months. Nearly one-third of the time, the index was at a new high within 10 months of the previous peak.

As for major pullbacks, the median duration was 17 months, with a drop of more than 30%. As I mentioned earlier, these declines are associated with recessions. But market pullbacks are often a leading indicator — meaning they signal an upcoming recession rather than the other way around. I’d also point out that our research suggests the U.S. economy is not currently exhibiting any of the obvious excesses or imbalances that have foreshadowed economic contractions. And while there has been recent concern about high equity valuations, our research indicates that valuations themselves are not a dependable predictor of market weakness.

Certainly, none of this inoculates the market from a sudden or sharp decline. Exogenous shocks such as geopolitical events and policy miscues can spark pullbacks. But history shows that it’s impossible to predict corrections with reliable accuracy. As always, the best strategy is to establish a thoughtful portfolio structure customized to your personal circumstances and stick with it through the inevitable gyrations in the market.

The above article originally appeared in the Fall 2017 issue of Quarterly Insights magazine.

Related Insights

Related Insights

-

-

Tax & Estate Planning

-

Sandra Morelli

Sandra Morelli