Retirement Income

Retirement Income

- Overestimating longevity could lead to reduced spending and withdrawal rates.

- Underestimating life expectancy, combined with too short of a planning horizon, can result in inadequate income in advanced retirement.

- Pensions, Social Security and annuities are uniquely suited to addressing and combating longevity risk.

As we explored in our article on longevity, Americans are living longer than ever before. This raises some key challenges for investors and their financial professionals when planning for retirement income.

One of these challenges: How long do I plan for?

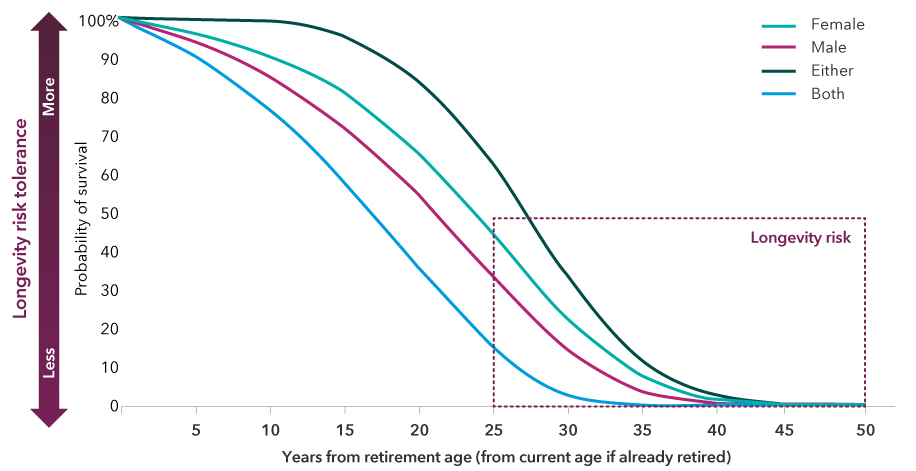

As one of the goals of retirement income planning is to provide an income stream that lasts as long as the client’s life, the answer to this question may shock many. Misjudging longevity can have meaningful implications: Plan on too long, the client may leave money behind, but not planning long enough runs the risk your client may run out of money. Understanding expected mortality — individual and spousal — is a good first step.

However, expected mortality is just the probability “on average” and it is unlikely your clients will want to plan for average. So, how long should they plan for? It depends a bit upon what they consider “reasonable.” A female retiring at age 65 (non-smoker, in average health) has a roughly 1-in-4 chance of living to age 95* and a 1-in-10 chance of needing income to age 99.* Given the very real “fear of outliving their income,” many investors/clients may “reasonably” want their retirement income plan to consider at least a 1-in-10 probability of running out of money.

Some clients may favor an even more conservative plan. For a 65-year-old couple in average health, this could mean planning to live to 100,* or even 105, translating into a 35-to-40-year retirement planning horizon. While this is a daunting horizon for many investors and for retirement income planning, one way to approach the problem is to consider the risk tolerance of the investor and how risk tolerant their retirement income plan is to longevity. In other words, what is their longevity risk tolerance?

What happens if the planning horizon is too long?

When discussing retirement planning horizons with clients, consider starting the conversation by explaining the range of life expectancy projections and then compare those to how long they expect to live. It is likely that their “expectations” may be markedly different from reasonable outcomes.

The appropriate retirement planning horizon will depend on a tolerance for longevity risk. That is, how sure do your clients want to be that they will not outlive at least a portion of their retirement income plan? And how well is their portfolio insulated against longevity? There is variability in tolerance for longevity risk that may be due to a personal concern of outliving income and how reliant their retirement income is on their investment portfolio.

For example, a 65-year-old female (non-smoker, in average health) retiring today is projected to have a 50% chance of living 23 years* in retirement. However, she would most likely want her plan to last longer than the “average” retirement length. Given that it is reasonable to plan for a 10% probability of her outliving her retirement income plan, she should consider planning for 34 years* in retirement, bringing her to age 99.

Probability of living for a specified number of years

Source: American Academy of Actuaries and Society of Actuaries, Actuaries Longevity Illustrator, accessed 09/11/2023. Actuary parameters are for non-smokers in average health retiring at age 65.

While it may be prudent to plan for a longer retirement horizon, the tradeoff would be that a client’s lifestyle and spending may be unnecessarily constrained to allow the retirement portfolio to last longer. And of course, this will have implications for investment allocation decisions. The good news about this approach is that clients are much more likely to maintain their standard of living throughout retirement and avoid the necessity of cutting back when they are most vulnerable. And, there is also a higher likelihood of leaving a larger-than-planned legacy due to spending less, which may make future generations happy.

What happens if the planning horizon is too short?

Planning for a shorter retirement horizon may lead to overspending early on and the need for lifestyle adjustments later. It is important that clients realize the point at which a short horizon plan runs into trouble, as returning to fulfilling work may prove difficult, and any legacy planning may fail as well.

For example, a 65-year-old female client with a higher longevity-risk tolerance may be willing to accept a greater chance (more in line with the “average” of a 50% probability) of planning for her income to last only 23 years* to age 88. However, planning for a shorter horizon may not change her possibility of living to 100. For clients seeking a short planning horizon, it is critical that a portion of their retirement income comes from protected lifetime income sources such as pensions, annuities and Social Security, all of which may be insulated from longevity. Having a portion allocated to protected lifetime income limits an already vulnerable plan from unexpected events such as market downturns and inflation. This additional risk transfer strategy shifts the need from thinking about clients’ longevity risk tolerance in its totality, but you do need to get your clients to think about what happens should they live longer than their plan has anticipated.

What is an appropriate planning horizon?

It depends upon your definition of what is “reasonable.” A planning horizon to a 10% probability may be reasonable for many. Tools such as the Society of Actuaries’ Longevity Illustrator can help to provide a range of life-expectancy probabilities for longevity risk that may help lead to a reasonable retirement planning horizon.

The Portfolio Reliance Calculator can also help you estimate how much of clients’ retirement income portfolios are subject to longevity risk. Because as reliance on the portfolio for income increases, so does the potential sensitivity to longevity among other risks, affecting the overall retirement income strategy of the portfolio.

To be sure, there are different strategies for planning income for a short or long retirement. Determining clients’ longevity risk, revisiting their circumstances often and being prepared for the unexpected can be a sound approach to helping clients have appropriate income in retirement.

* American Academy of Actuaries and Society of Actuaries, Actuaries Longevity Illustrator (accessed 09/11/2023).

Our latest insights

-

-

Target Date

-

Practice Management

-

Participant Engagement

-

Practice Management

RELATED INSIGHTS

-

Retirement Income

-

Practice Management

-

Defined Contribution

Never miss an insight

The Capital Ideas newsletter delivers weekly investment insights straight to your inbox.

Kate Beattie

Kate Beattie